|

|

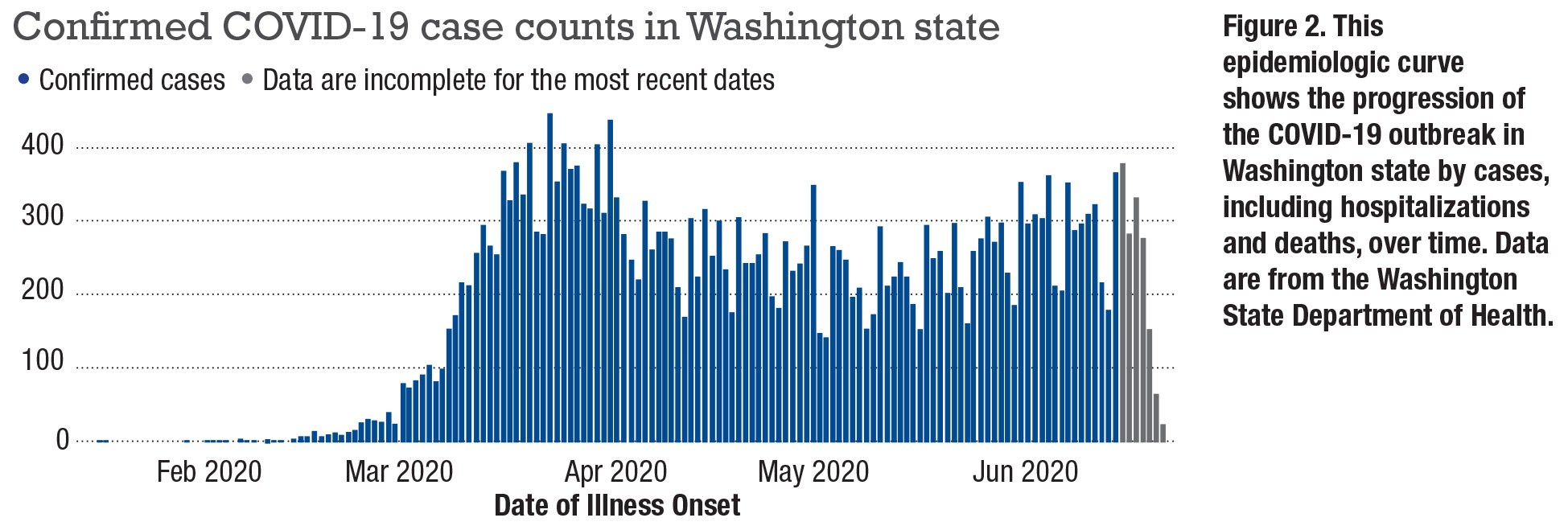

COVID-19 has had a profound impact on our practice as retina specialists. On January 20, Washington state, where we practice, confirmed the first COVID-19 case in the United States. Seattle rapidly became the country’s first hot spot and where the community transmission of the disease was first noted.1

Patients with COVID-19 have complained of visual impairment,2 with recent reports of subtle retinal findings without associated vision changes.3

As retina specialists, we have a unique risk of exposure because we come into close face-to-face proximity with our patients, particularly during intravitreal injections, laser procedures and even basic slit lamp examinations. As ophthalmologists practicing in one of the first epicenters of the country, we quickly reduced the volume of clinic visits and restricted patient encounters to urgent and emergent visits to slow the spread of the virus and preserve resources.

While we attempted to limit potential interactions with COVID-19 positive patients in clinics, we were also responsible for seeing patients who came in through the emergency department with acute eye symptoms who needed to be managed with COVID-19 precautions. Due to the nature of our specialty, many patients have eye conditions that require urgent care. Here we discuss the surgical evaluation and management of one of our practice’s first COVID-19-positive patients.

Relying on ED personnel

In April, a middle-aged man with a history of recent mild respiratory symptoms and known exposure to family members positive for COVID-19 presented to the Harborview Medical Center emergency department with a gradual decrease in vision in one eye. The patient was first tested for COVID-19 using a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of a sample obtained by nasopharyngeal swab. The test was positive and the patient was placed in a negative-pressure room for ophthalmic examination.

He did not require any supportive therapy for his respiratory symptoms. We quickly determined that a powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) could not be used to carry out an indirect dilated fundus exam and that an N95 with a face mask was necessary.

Fortunately, our ED had well-trained personnel to help us don and doff protective gear so we could safely enter and exit the room to examine the patient. The patient was diagnosed with a macula-involving retinal detachment in the symptomatic eye.

Given that this patient had a single superior retinal tear in a phakic eye, we offered him a pneumatic retinopexy while noting that this technique would mean he would need closer postoperative follow-up with possible later interventions such as laser, which could be challenging to coordinate because of his COVID-19 status. After we had a complete discussion of pneumatic retinopexy vs. pars plana vitrectomy, he elected to proceed with a PPV for the RD repair.

Planning the operation

|

We planned the operation for a few days later, and we discovered the challenges and intricacies of scheduling a COVID-19 patient for outpatient surgery. As we soon learned, this was the first COVID-19-positive patient to have outpatient surgery at Harborview Medical Center. After extensive discussion with the perioperative staff, anesthesiologists and our surgical team, we developed a plan to keep all involved parties, including the ill patient, the other patients scheduled for eye surgery that day and all surgical staff, as safe as possible.

On the morning of the surgery, the patient was again placed in a negative-pressure room in the preoperative area, and trained personnel helped us don and doff before were entered and after we exited the room. Another interesting twist was that the patient’s spouse also tested positive for COVID-19 and had to be placed in an isolated waiting room for the duration of the case.

Because using PAPRs would have hindered our ability to operate at the microscope, we wore N95 masks with an overlying eye-shield for added protection. While we considered avoiding intubation to decrease the risk of viral-particle aerosolization and performing the case under monitored anesthesia care, the patient strongly favored general anesthesia, which was performed with only the anesthesiologist (who was able to wear a PAPR) in the operating room.

Once the patient was induced and fully intubated to avoid exposure to aerosolized virus particles, we entered the OR. After we completed the surgery, we promptly exited the room before the patient was extubated, again to decrease the risk of exposure. The patient was then allowed to recover initially and wake up in the OR for a period of time before being transported back to a negative-pressure room for recovery.

Postoperative care

On post-op day-one and week-one visits, we examined the patient in a negative-pressure room in our clinic. We asked the patient to arrive early before other patients. To avoid exposure and contamination, we organized a station outside the room to don and doff as we had done previously in the ED and OR.

By the one-month visit, the patient had fully recovered from his respiratory symptoms. His retina was attached, and his vision had improved from counting fingers preoperatively to 20/50 with correction. The patient still had a gas tamponade agent in his eye, and we will see him again in a month. Overall, he is healing well after a safe and successful surgical intervention.

|

Three key lessons in COVID-19 care

This case highlights three important lessons regarding the technical challenges, resources and significance of caring for patients during a pandemic:

- Creating a safer environment in the exam room and OR for both provider and patient has its challenges but is possible and achievable.

- We must allocate an immense amount of resources to care for COVID-19 patients, especially those undergoing surgery. We were fortunate to have excellent resources and infrastructure in place to face this challenge.

- COVID-19-positive patients deserve the same care and compassion that we provide to any other patient. It can be isolating to be placed in a negative-pressure room and to see your physician donned in protective gear. We must remember to maintain the human connection. Even as we maintain appropriate social distancing, we should ensure that the patient feels cared for and not ostracized.

At the one month post-op, the patient and his wife were overjoyed that they could be examined in a normal room and we could interact with them with less personal protective equipment than we had donned for prior visits.

Bottom line

If we learned one thing from COVID-19, it’s that human life is precious and that it is possible to connect with others despite barriers. While we’re retina specialists, we’re physicians first and play an impactful role in not only treating patients’ eye disease, but also their spiritual and mental well-being. Our duty to treat patients with retinal disease remains even during a pandemic, and we’re able to employ safe measures regardless of their COVID-19 status.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, here at UW, our Eye Institute and hospital have implemented many changes. We will continue to apply the lessons learned from our early encounters with COVID-19 patients to the management of future patients affected by this novel virus.

We hope to learn more about this disease. We recently received approval from the UW internal review board and COVID-19 Research Review Working Group to study the ocular manifestations of this virus in our patient population. RS

REFERENCES

1. Chu HY, Englund JA, Starita LM, et al. Early detection of covid-19 through a citywide pandemic surveillance platform. N Engl J Med. Published online May 1, 2020. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2008646

2. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683-690.

3. Marinho PM, Marcos AAA, Romano AC, Nascimento H, Belfort R. Retinal findings in patients with COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1610.