|

|

Bios Dr. Moussa is an attending ophthalmologist at UC-Davis. Dr. Thomas is a partner in vitreoretinal surgery and uveitis at Tennessee Retina. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Nelson and Dr. Moussa have no relationships to disclose. Dr. Thomas is a consultant for Allergan/AbbVie, Alimera Sciences, Avesis, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals, Genentech/Roche and Novartis. |

Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome, also known as Ellingson syndrome, was first described in 1977.1 The syndrome is classically characterized by the triad of intraocular inflammation, recurrent hyphema and elevated intraocular pressure occurring in pseudophakic patients. Mechanical irritation of the iris, ciliary body or iridocorneal angle by foreign material, typically an intraocular lens implant, can result in pigment dispersion, hyphema, vitreous hemorrhage, increased intraocular pressure, intraocular inflammation and/or cystoid macular edema.

Diagnosis of UGH syndrome can be challenging due to this wide spectrum of findings. Definitive treatment is surgical, involving IOL repositioning, exchange or removal to resolve the cause of chafing.

UGH and anterior chamber IOLs

Thomas Ellingson, MD, first observed this syndrome in patients with a specific brand of anterior chamber IOLs, the Surgidev Mark VIII, and later observed it upon removal of the lenses after the footplates had warped.1 He hypothesized that the footplates were mechanically irritating the iridocorneal angle structures, leading to recurrent hyphema and uveitis. Scanning electron microscopy of IOLs that were explanted due to UGH syndrome demonstrated irregular or sharpened IOL edges, along with deposition of inflammatory cells, erythrocytes and fibrous tissue at these edges, further supporting Dr. Ellingson’s hypothesis.2

Other groups later further implicated anterior chamber IOLs in UGH syndrome.3,4 These findings led to a movement toward improved quality control of IOL manufacturing as well as a preference for placing IOLs in the posterior chamber. Consequently, the incidence of UGH syndrome decreased in the subsequent years.5

UGH with posterior chamber IOLs

While anterior chamber IOLs are still a potential instigator of UGH syndrome, it was also shown to develop with IOLs placed in the posterior chamber. In 2009, a series of cases in which single-piece acrylic (SPA) IOLs were placed in the ciliary sulcus demonstrated an increased risk of UGH syndrome, as a majority of these patients developed pigment dispersion and iris transillumination defects, with smaller portions developing increased intraocular pressure and/or hyphema.6

SPA IOLs aren’t manufactured for placement in the ciliary sulcus because the thick haptics, rough surface and lack of vaulting increase the risk of chafing of the posterior iris and ciliary body. So the recommendation is that, when intracapsular IOL placement isn’t achievable, a three-piece IOL should be placed in the ciliary sulcus, with suture fixation if the capsular support isn’t sufficient.

|

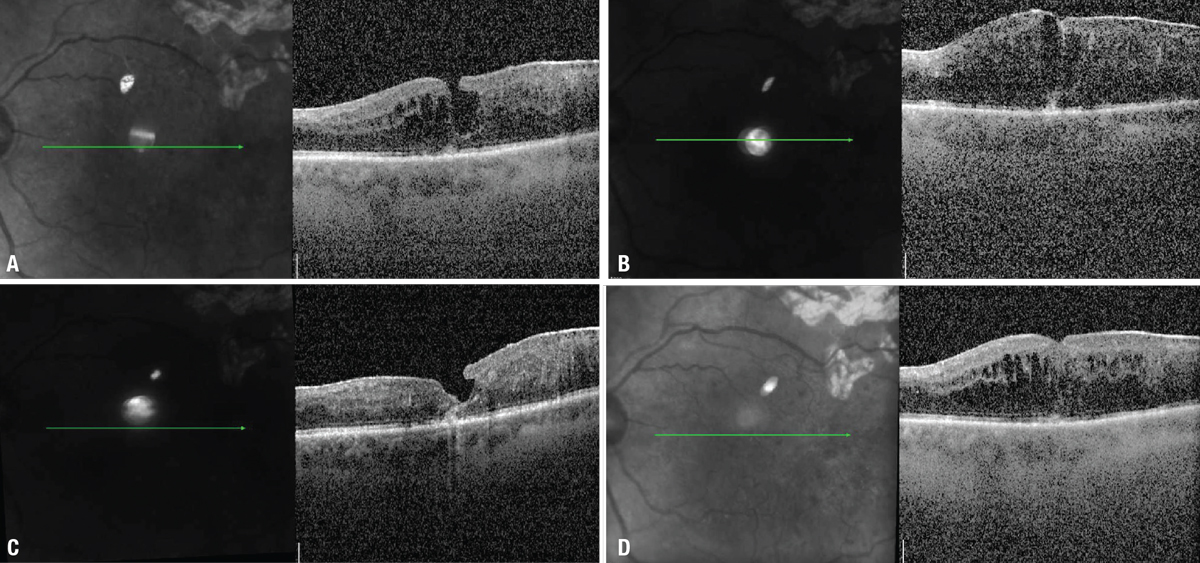

| Figure 1. A) Optical coherence tomography scans demonstrate macular edema which (B) didn’t improve after three intravitreal injections of aflibercept. C) The macular edema improved notably after an intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide, although (D) it recurred four weeks later. |

Rare cases of UGH syndrome with intracapsular SPA IOLs have also been reported, in which iris or ciliary body chafing was attributed to three causes:

- zonular laxity causing pseudophacodonesis;7

- anterior capsular fibrosis chafing anteriorly and displacing ciliary processes in plateau iris configuration;7 or

- extensive capsular fibrosis (Soemmering ring) around the IOL haptics.8

Other causes of UGH syndrome may also be intraocular implants other than IOLs, including iris implants,9 endocapsular tension rings10 or glaucoma drainage implants,11 though IOLs remain the most typical causative implant.

The retina specialist’s role

Patients with UGH syndrome may be referred to a retina specialist for evaluation due to its potential for posterior-segment findings. A pseudophakic patient with a vitreous hemorrhage or macular edema of unclear etiology should raise suspicion for UGH syndrome. The workup should consist of a careful anterior segment examination, including evaluation of the IOL design, stability and haptic position in relation to the capsule.

Ultrasound biomicroscopy is useful in identifying any point of contact between IOL haptics and the posterior iris or ciliary processes.12 We’ll review two cases of UGH syndrome that presented with vitreoretinal involvement and discuss the key features on examination and imaging that helped us diagnose UGH syndrome as the cause of the posterior-segment pathology.

Case 1: Recurring UGH with DR

A 71-year-old man with a history of quiescent proliferative diabetic retinopathy in both eyes presented for evaluation of presumed diabetic macular edema in the left eye (Figure 1A). Visual acuity was 20/100. He received intravitreal aflibercept every four weeks for 12 weeks, but the macular edema continued to worsen (Figure 1B). He then underwent intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (4 mg) injection, with significant improvement in macular edema two weeks later (Figure 1C).

|

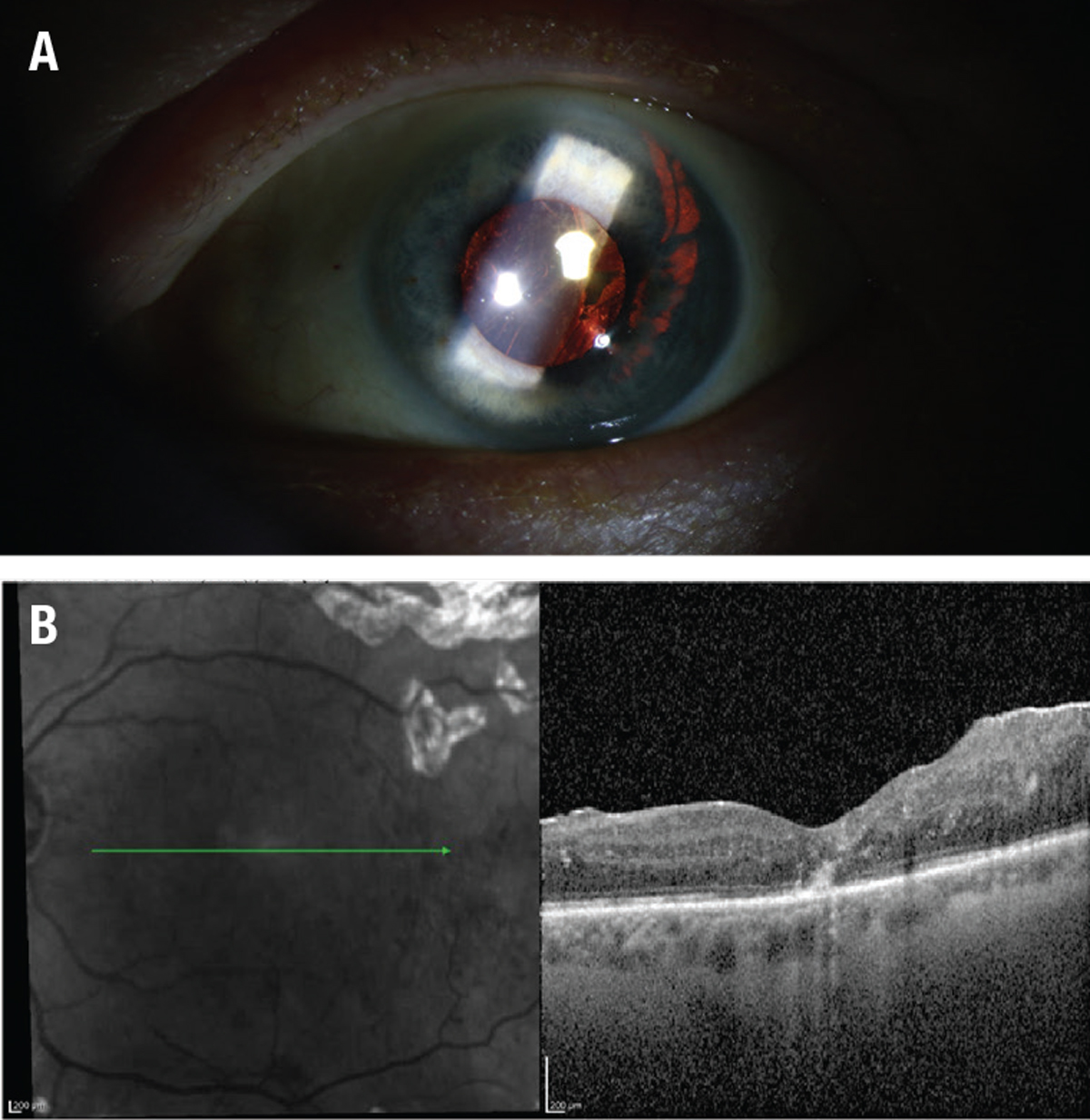

| Figure 2. A) Slit-lamp photography shows a temporal iris transillumination defect in the shape of a lens haptic. B) The macular edema resolved postoperatively, as optical coherence tomography demonstrates. |

Four weeks after the injection, the macular edema recurred (Figure 1D). A careful exam of the anterior segment showed a single-piece IOL in the sulcus with a trans-illumination defect in the iris in the shape of a haptic (Figure 2A). He was diagnosed with UGH syndrome and subsequently underwent pars plana vitrectomy, epiretinal membrane and internal limiting membrane peel, IOL removal and posterior sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone acetonide injection. The macular edema resolved postoperatively (Figure 2B). His visual acuity was 20/50 with a contact lens and he chose to remain aphakic.

Case 2: Transient vision changes

A 73-year-old woman presented with transient vision changes in the left eye. She described them as a sudden appearance of dark cobwebs, haziness and cloudiness that occurred three or four times over the past three months, lasting for hours each time. She reported a history of uncomplicated cataract surgery in both eyes four years earlier.

The examination revealed pseudophakia in both eyes, but was otherwise unremarkable. Based on the patient’s symptoms, amaurosis fugax was a concern. The workup for embolic disease was unremarkable. Carotid ultrasound revealed a 50 to 69 percent stenosis in the left internal carotid artery. Given the possibility for amaurosis fugax, the patient started on clopidogrel.

|

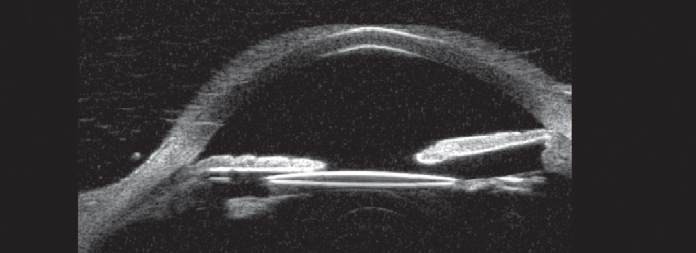

| Figure 3. Ultrasound biomicroscopy shows dislocation of a portion of the intraocular lens out of the capsular bag with a point of contact between the lens optic and the posterior iris. (Courtesy Karishma Chandra) |

The patient continued to have recurrent symptoms. She presented three months later with elevated IOP, corneal edema, iritis and vitreous hemorrhage. An anterior segment exam showed temporal dislocation of a one-piece IOL out of the bag into the sulcus. Ultrasound biomicroscopy confirmed chafing of the intraocular lens in the sulcus and the posterior iris (Figure 3). The patient underwent pars plana vitrectomy and IOL exchange with a three-piece intraocular lens in the sulcus and subsequent resolution of symptoms.

Bottom line

UGH syndrome can cause vitreoretinal complications, such as CME and vitreous hemorrhage, and can masquerade as a primary retinal disease. Retina specialists should perform a careful exam of the lens in pseudophakic patients with CME or vitreous hemorrhage of unclear etiology to rule out UGH syndrome. Careful attention should be paid to the type of IOL placed (single- or three-piece) and the location of the lens relative to the lens capsule.

A single-piece lens in the ciliary sulcus should raise a high suspicion for UGH. Ultrasound biomicroscopy can confirm a malpositioned IOL, especially if it’s difficult to visualize the lens capsule on exam, which can happen with small pupils.

Surgery is indicated for treatment of UGH syndrome, either by repositioning a dislocated lens into the capsular bag or removing the malpositioned lens and replacing it with a three-piece lens in the sulcus—provided capsular support is sufficient. But if capsular support isn’t sufficient to support a sulcus lens, consider a scleral-fixated or anterior-chamber IOL. RS

REFERENCES

1. Ellingson T. The uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome associated with the Mark Viii anterior chamber lens implant. Am Intra-Ocular Implant Soc J. 1978;4:50-53.

2. Drews RC, Smith ME, Okun N. Scanning electron microscopy of intraocular lenses. Ophthalmology. 1978;85:415-424.

3. Brodstein RS. Hyphema syndrome with anterior lenses. J Am Intraocul Implant Soc. 1978;4:64-65.

4. Keates RH, Ehrlich DR. “Lenses of Chance”: Complications of anterior chamber implants. Ophthalmology. 1978;85:408-414.

5. Le T, Rhee D, Sozeri Y. Uveitis–glaucoma–hyphema syndrome: A review and exploration of new concepts. Curr Ophthalmol Reports. 2020;8:165-171.

6. Chang DF, Masket S, Miller KM, et al. Complications of sulcus placement of single-piece acrylic intraocular lenses. Recommendations for backup IOL implantation following posterior capsule rupture. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:1445-1458.

7. Zhang L, Hood CT, Vrabec JP, Cullen AL, Parrish EA, Moroi SE. Mechanisms for in-the-bag uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40:490-492.

8. Bryant T, Feinberg E, Peeler C. Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome secondary to a Soemmerring ring. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43:985-987.

9. Arthur SM, Wright MM, Kramarevsky N, Kaufman SC, Grajewski AL. Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome and corneal decompensation in association with cosmetic iris implants. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:790-793.

10. Cheung AY, Price JM, Heidemann DG, Hart Jr. JC. Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome caused by dislocated Cionni endocapsular tension ring. Can J Ophthalmol. 2018;53:e213-e214.

11. Hou A, Hasbrook M, Crandall D. A case of uveitis-hyphema-glaucoma syndrome due to EX-PRESS glaucoma filtration device implantation. J Glaucoma. 2019;28:e159-e161.

12. Piette S, Canlas OAQ, Tran HV, Ishikawa H, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Ultrasound biomicroscopy in uveitis-glaucoma- hyphema syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:839-841.