|

|

Bios Dr. Venkat is a medical retina and uveitis specialist at the University of Virginia in Dr. Abou-Samra is a fourth-year resident at the University of Virginia. Dr. Thomas is a partner in vitreoretinal surgery and uveitis at Tennessee Retina. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Venkat is a consultant to Apellis Pharmaceuticals and EyePoint Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Abou-Samra has no relevant relationships to disclose. Dr. Thomas is a consultant to Allergan/AbbVie, Alimera Sciences, Avesis, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals, Genentech/Roche and Novartis. |

Choroidal neovascular membrane is a common cause of vision loss resulting from disruption in the integrity of Bruch’s membrane and the retinal pigment epithelium. A wide array of pathological conditions, such as myopia and macular degeneration, can lead to involvement of such structures and downstream angiogenesis.

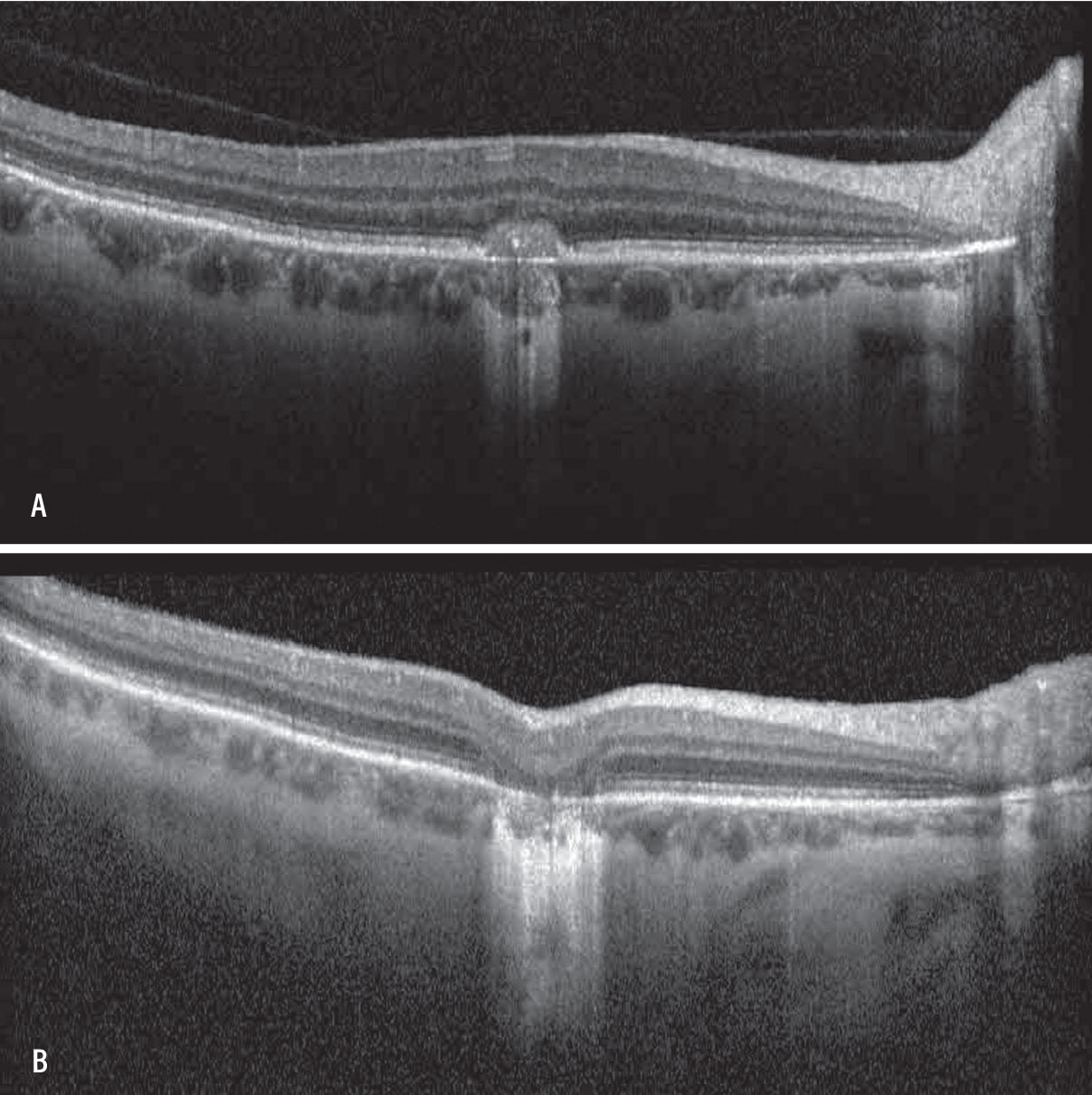

Inflammatory etiologies can also cause secondary choroidal neovascular membrane. Inflammatory CNVM can be seen in noninfectious processes such as punctate inner choroidopathy (Figure), Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, multifocal choroiditis, sarcoidosis and serpiginous choroiditis. It can also be found in infectious posterior uveitis such as toxoplasmosis,1 tuberculosis2 and presumed ocular histoplasmosis.3

Why it occurs

A complex interplay of inflammatory mediators causes CNVM, including growth factors, interleukins and cytokines with resultant neoangiogenesis and remodeling of the extracellular matrix.4 Due to a shift in balance between inhibitory and stimulatory mediators in the retina, the pathway of neoangiogenesis and inflammation can shift to fibrosis and scarring, known as the involutional phase.5,6 For this reason, early diagnosis and prompt management are essential to prevent irreversible vision loss.

Diagnostic imaging options

Treatment of CNVM in the setting of infectious uveitides requires treatment of the underlying infectious process in concert with conventional management of CNVM. The remainder of this article will review the management of inflammatory CNVM in the setting of noninfectious uveitis.

In addition to the use of traditional treatment strategies for CNVM, diagnosis and appropriate management of the underlying uveitic process is important. Appropriate multimodal imaging, including fluorescein angiography, indocyanine green angiography and fundus autofluorescence, can help determine whether the chorioretinal inflammation is active or inactive. Determining the underlying disease activity is crucial because it impacts the best way to manage secondary CNVM.

Inflammatory CNVM can be challenging to diagnose and differentiate from other entities. Uveitic cystoid macular edema can present with intraretinal fluid, subretinal fluid and outer retinal changes on optical coherence tomography that can make it difficult to distinguish from inflammatory CNVM, especially in patients with chronic inflammatory disease. Inflammatory CNVM often presents with subretinal hyperreflective material that can distinguish it from inflammatory CME.

FA can help distinguish between inflammatory pigment epithelial detachment and CNVM, which can often look similar. OCT angiography is another modality that can be helpful in making this distinction. However, in spite of these imaging modalities, differentiating between these two entities can still be difficult.

|

|

A) Optical coherence tomography of the macula of the right eye in a patient with a history of punctate inner choroidopathy showing classic choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM). B) OCT of the macula of the right eye demonstrating resolution of CNVM and subsequent outer retinal atrophy after intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy. |

Treatment options

Inflammatory PED is best treated with steroid therapy or immunomodulatory therapy, while CNVM is best treated with the following treatments:

•Anti-VEGF therapy. Multiple case series have demonstrated the utility of anti-VEGF agents for treatment of inflammatory CNVM.7 The MINERVA study showed benefit of ranibizumab for secondary CNVM, leading to the approval of ranibizumab by the European Union for the treatment of inflammatory CNVM.

Although no consensus exists on an established treatment protocol for anti-VEGF duration and usage, an international study that looked at 24-month outcomes in treating inflammatory CNVMs either with three monthly anti-VEGF injections followed by pro re nata dosing or PRN from the start of therapy showed no difference in outcomes or recurrence rates between the two groups.8

•Oral steroids. When the underlying uveitis appears active and concurrent CNVM is present, consider oral steroids alongside intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy. Local steroid therapy may also be helpful. Several case series have shown benefit with the use of injectable corticosteroids, including sub-Tenon’s9 and intravitreal injections.10

Active uveitis should be controlled and well-managed because incomplete control of inflammation can lead to ongoing CNVM formation despite regular anti-VEGF therapy. In some cases, systemic immunotherapy is needed in concert with ongoing anti-VEGF injections for management of secondary CNVM. Intravitreal immunomodulatory therapy, such as intravitreal methotrexate or rituximab, is another therapeutic option,11 although its use hasn’t been validated by larger studies.

Bottom line

Secondary CNVM in the setting of uveitis should be managed by ensuring that the underlying primary inflammatory process is controlled. In the setting of infectious uveitis, this entails appropriate anti-infective therapy in concert with intravitreal anti-VEGF. In the setting of noninfectious chorioretinal inflammation, systemic or local steroid therapy in concert with anti-

VEGF can be considered. In some cases, immunomodulatory therapy is needed for durable remission along with ongoing anti-VEGF therapy. RS

REFERENCES

1. Mushtaq F, Ahmad A, Qambar F, Ahmad A, Zehra N. Primary acquired toxoplasma retinochoroiditis: Choroidal neovascular membrane as an early complication. Cureus. 2019;11:e4001.

2. Chung YM, Yeh TS, Sheu SJ, Liu JH. Macular subretinal neovascularization in choroidal tuberculosis. Ann Ophthalmol. 1989;21:225–9.

3. Liu TYA, Zhang AY, Wenick A. Evolution of choroidal neovascularization due to presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome on multimodal imaging including optical coherence tomography angiography. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2018;2018:4098419.

4. Obasanmi G, Tian Y, Cui JZ, et al. Granzyme B degrades extracellular matrix and promotes choroidal neovascularization in an ex-vivo microvascular angiogenesis model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62:2709.

5. Grossniklaus HE, Kang SJ, Berglin L. Animal models of choroidal and retinal neovascularization. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29:500–519.

6. Jensen EG, Jakobsen TS, Thiel S, Askou AL, Corydon TJ. Associations between the complement system and choroidal neovascularization in wet age-related macular degeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:9752.

7. Agarwal A, Invernizzi A, Singh RB, et al. An update on inflammatory choroidal neovascularization: Epidemiology, multimodal imaging, and management. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2018;8:13.

8. Invernizzi A, Pichi F, Symes R, et al. Twenty-four-month outcomes of inflammatory choroidal neovascularisation treated with intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factors: A comparison between two treatment regimens. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:1052-1056.

9. Martidis A, Miller DG, Ciulla TA, Danis RP, Moorthy RS. Corticosteroids as an antiangiogenic agent for histoplasmosis – related subfoveal choroidal neovascularisation. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1999;15:425–428.

10. Gopal L, Sharma T. Use of intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:431-435.

11. Mateo-Montoya A, Baglivo E, de Smet MD. Intravitreal methotrexate for the treatment of choroidal neovascularization in multifocal choroiditis. Eye (Lond). 2013;27:277–278.