|

Bios Dr. Bonnell is an ophthalmology resident at the University of Washington in Seattle. |

An 83-year-old male presented to the emergency department for evaluation of a central scotoma in

the right eye for one day. He reported that, before the symptoms came on, he had applied pressure to the right globe with his finger. When he removed his finger, he noticed that there was a dark, flower-shaped spot in the center of his vision in that eye.

Examination findings and work-up

Best corrected visual acuity was 20/70 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. His pupils were equal and reactive without a relative afferent pupillary defect, and intraocular pressures were within normal limits in each eye.

The slit lamp examination was notable for a posterior vitreous detachment in both eyes. A dilated fundus examination revealed a small, full-thickness macular hole in the right eye.

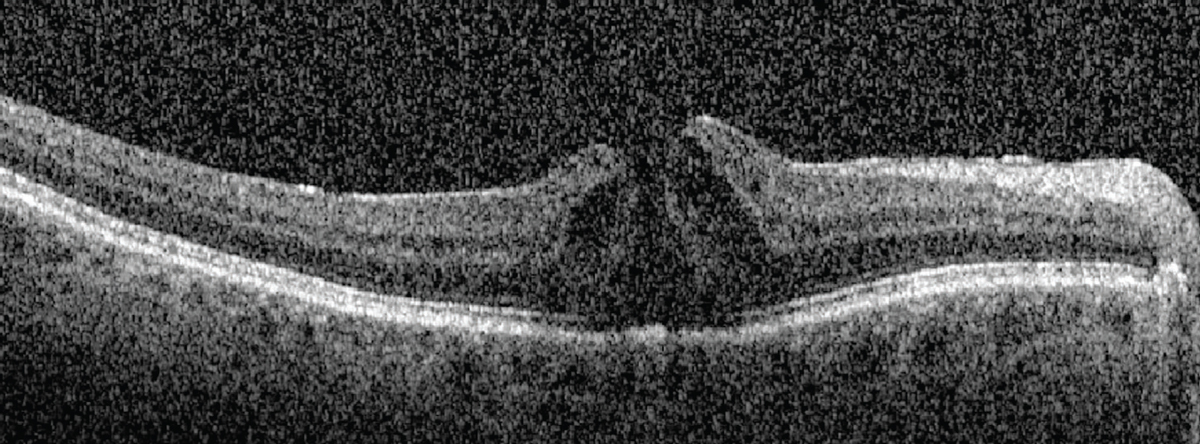

Optical coherence tomography of the macula in the right eye revealed an absent hyaloid face (Figure 1). Notably, there was a small, full-thickness macular hole in the right eye, measuring 193 µm. Cystic intraretinal fluid collected at the edges of the hole.

Diagnosis

We diagnosed the patient with a full-thickness macular hole likely secondary to self-induced trauma following digital pressure on the globe.

|

| Figure 1. Optical coherence tomography of the right eye at the time of presentation demonstrates an absent hyaloid face along with a small, full-thickness macular hole. Cystic intraretinal fluid had collected at the edges of the hole. |

Management

The patient was referred to the retina service for a follow-up evaluation four weeks after the symptom first appeared. After this period of observation, best-corrected visual acuity remained 20/70 in the right eye and the macular hole persisted with an increase in the amount of IRF at the hole margins.

We considered three options: observation; medical treatment; and surgical intervention. Given the small size of the macular hole, the absence of vitreomacular traction and the presence of IRF at the hole margin, we decided to start medical treatment, prescribing topical ketorolac 0.5% q.i.d. in the right eye.

Macular hole closure

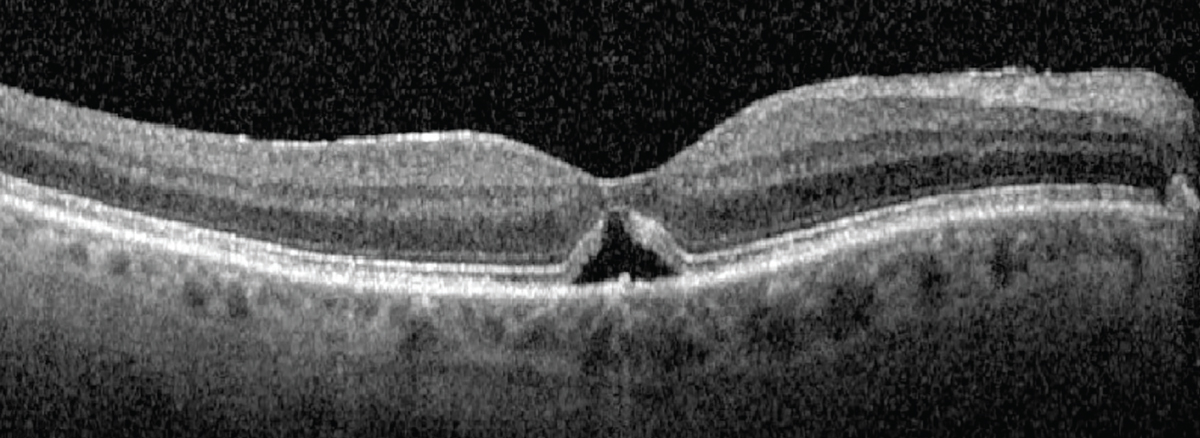

We saw the patient again five weeks after starting treatment. At that visit, he reported an improvement in his symptoms. BCVA remained 20/70 in the right eye. Examination and OCT (Figure 2) determined the closure of the macular hole and resolution of the IRF with residual subretinal fluid. We told the patient to keep applying ketorolac q.i.d. in the right eye.

At the most recent follow-up appointment, 17 weeks after the patient started treatment, he remains on ketorolac at the same dose. BCVA is 20/30 in the right eye. The macular hole has remained closed. Persistent trace subretinal fluid continues to improve at each visit.

|

| Figure 2. Five weeks after starting treatment with topical ketorolac, optical coherence tomography demonstrates macular hole closure and resolution of intraretinal fluid with persistent subretinal fluid. |

Why medical therapy?

Vitreomacular traction has been thought to play a role in the development of macular holes for more than 30 years.1 This theory has been widely accepted and supported by the fact that reducing traction on the retina with vitrectomy, with or without inner limiting membrane peeling or gas tamponade, has long been a successful treatment for macular holes.2 In many cases, OCT imaging demonstrates the progression of vitreoretinal traction in the development of macular holes.3

However, some macular holes develop and persist in the absence of retinal traction.4 In these cases, patients may have had vitrectomy previously or OCT didn’t show evidence of vitreomacular traction in the affected eye. These observations have led to a supplemental theory of macular hole formation: the hydration theory.5

The hydration theory of macular hole development surmises that IRF at the macular hole edges distorts the normal retinal architecture and precludes hole closure. By reducing this fluid, the hole edges can reapproximate and close.5,6 Surgeons are now using medical therapies targeting this fluid before taking select patients to the operating room.

Medication selection

The literature on macular hole closure following medical therapy is growing. Authors have reported on the use of a variety of medical therapies and doses targeting macular edema.

Selected therapies include topical steroids and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including ketorolac, as we used in this case.6–10 Other therapies include topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.11

Considering a therapeutic effect

Macular holes have been known to close spontaneously. It’s possible that our patient, and others reported in the literature, would have closed regardless of medical intervention. Spontaneous macular hole closure has been reported in 4 to 11.5 percent of cases.12 Spontaneous closure is more likely in cases of small holes, especially smaller than 250 µm, without vitreomacular traction—again, as was the case for our patient.13

However, two reports have described a close association between treatment and macular hole status.7,8 In both cases, patients demonstrated macular hole closure after topical NSAID and steroid exposure, respectively. What’s interesting is that both cases had macular hole recurrence after the topical therapy was stopped, but then the holes closed again when the patients restarted the medications.

This relationship between medication exposure and macular hole status is interesting to consider, though not conclusive. We need prospective research to further elucidate this relationship.

Bottom line

A growing number of reports have described a relationship between medical treatments targeting IRF and macular hole closure, including this case. A large selection of medications and doses have been tried and reported in the literature.

In light of these reports, hope is emerging that medical treatment for macular holes may offer patients comparable visual and anatomic outcomes to surgery but with reduced morbidity. However, at this time we lack the evidence to support this hypothesis. We need to prospectively study medical therapy in the management of macular holes to better understand this relationship. RS

REFERENCES

1. Johnson RN, Gass JD. Idiopathic macular holes. Observations, stages of formation, and implications for surgical intervention. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:917-924.

2. Kelly NE, Wendel RT. Vitreous surgery for idiopathic macular holes. Results of a pilot study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:654-659.

3. Puliafito CA, Hee MR, Lin CP, et al. Imaging of macular diseases with optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:217-229.

4. Smiddy WE. Macular hole formation without vitreofoveal traction. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:737-738.

5. Tornambe PE. Macular hole genesis: the hydration theory. Retina. 2003;23:421-424.

6. Gentile RC, Eliott D, Rosen RB, Benevento J, Reppucci VS, Iezzi R. The combined tractional-hydration theory of idiopathic macular holes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:4325.

7. Kurz PA, Kurz DE. Macular hole closure and visual improvement with topical nonsteroidal treatment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1687-1688.

8. Bonnell AC, Prenner S, Weinstein MS, Fine HF. Macular hole closures with topical steroids. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2022;16:351-354.

9. Gonzalez-Saldivar G, Juncal V, Chow D. Topical steroids: A non-surgical approach for recurrent macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2019;13:93-95.

10. Khurana RN, Wieland MR. Topical steroids for recurrent macular hole after pars plana vitrectomy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2:636-637.

11. Sokol JT, Schechet SA, Komati R, et al. Macular hole closure with medical treatment. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5:711-713.

12. Yuzawa M, Watanabe A, Takahashi Y, Matsui M. Observation of idiopathic full-thickness macular holes: follow-up observation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:1051-1056.

13. Liang X, Liu W. Characteristics and risk factors for spontaneous closure of idiopathic full-thickness macular hole. J Ophthalmol. 2019;2019:4793764.