|

|

Bios

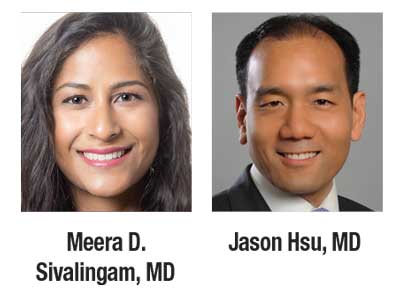

Dr. Sivalingam is a first-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow at Mid Atlantic Retina. Dr. Hsu is with Mid DISCLOSURES: Drs. Sivalingam and Hsu have no relevant financial relationships to disclose. |

A 69-year-old female was referred to our retina clinic for evaluation of floaters and blurred vision in both eyes for two weeks. Her medical history was significant for endometrial adenocarcinoma diagnosed 18 months earlier.

Work-up and imaging

Her visual acuity was 20/80 OD and 20/70 OS. Intraocular pressures were normal bilaterally. Her anterior segment exam revealed 1+ nuclear sclerosis in both eyes. Anterior chambers were quiet bilaterally. Fundus examination was significant for 1+ vitreous cell. The macula was flat.

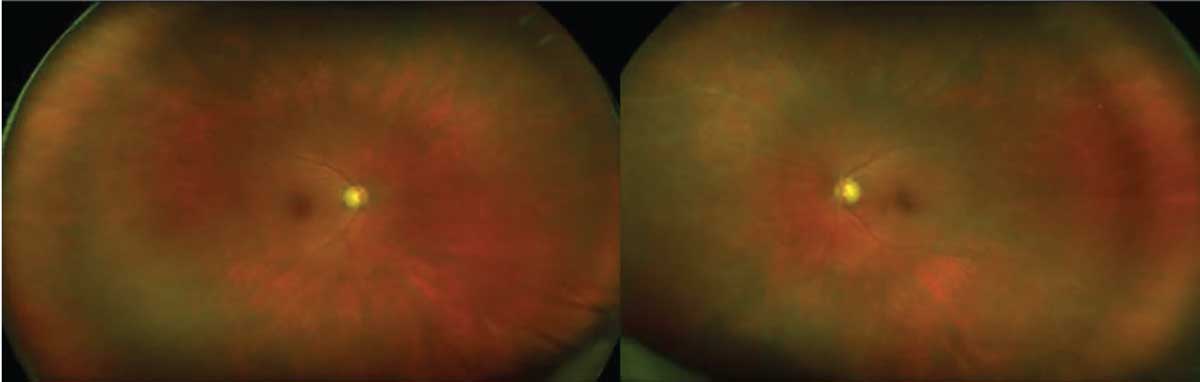

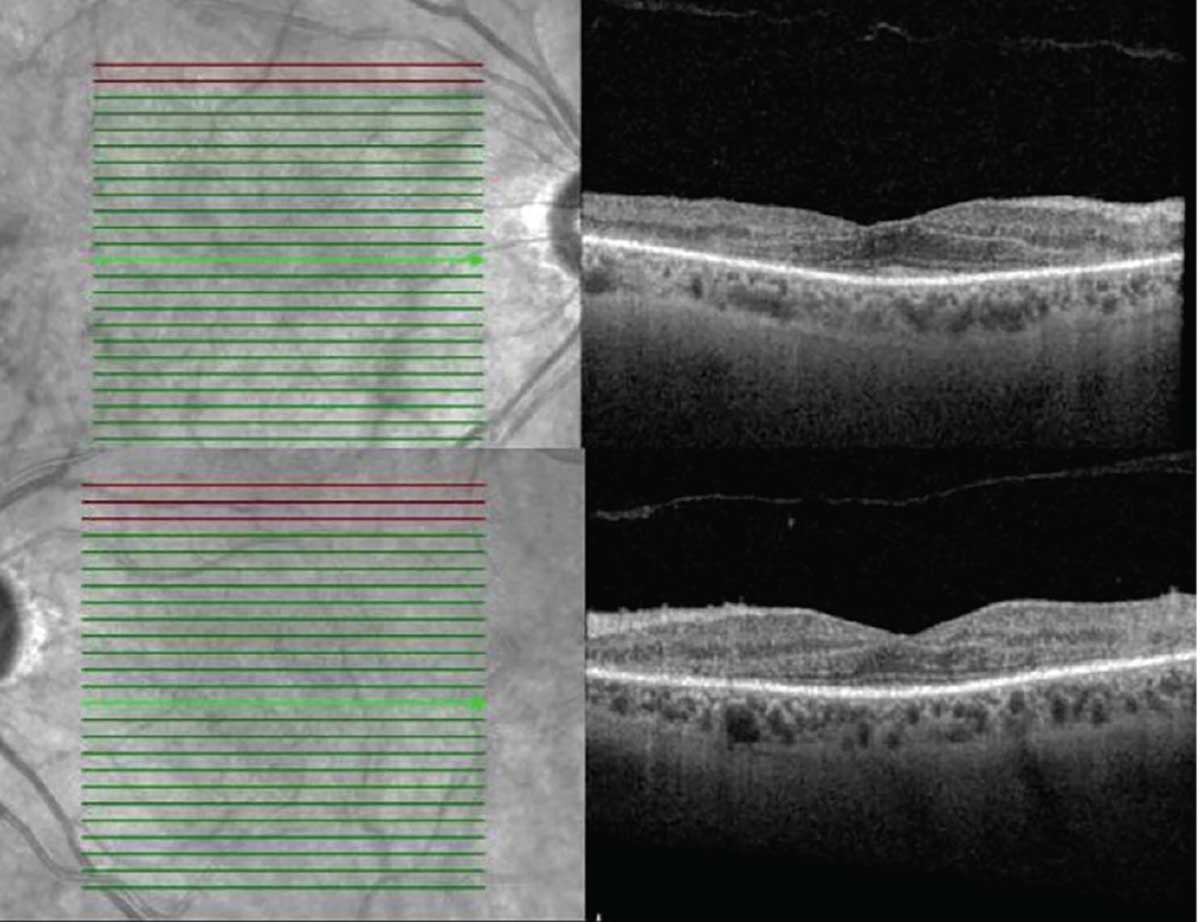

Marked arterial and venous sheathing was present in the periphery OU (Figure 1). Optical coherence tomography showed marked loss of the ellipsoid zone as well as significant loss of laminations of the outer plexiform and outer nuclear layers (Figure 2). Fundus autofluorescence revealed hyperautofluorescence of the posterior pole with mottled areas of hypoautofluorescence throughout the macula, as well as perivascular hyperautofluorescence OU (Figure 3).

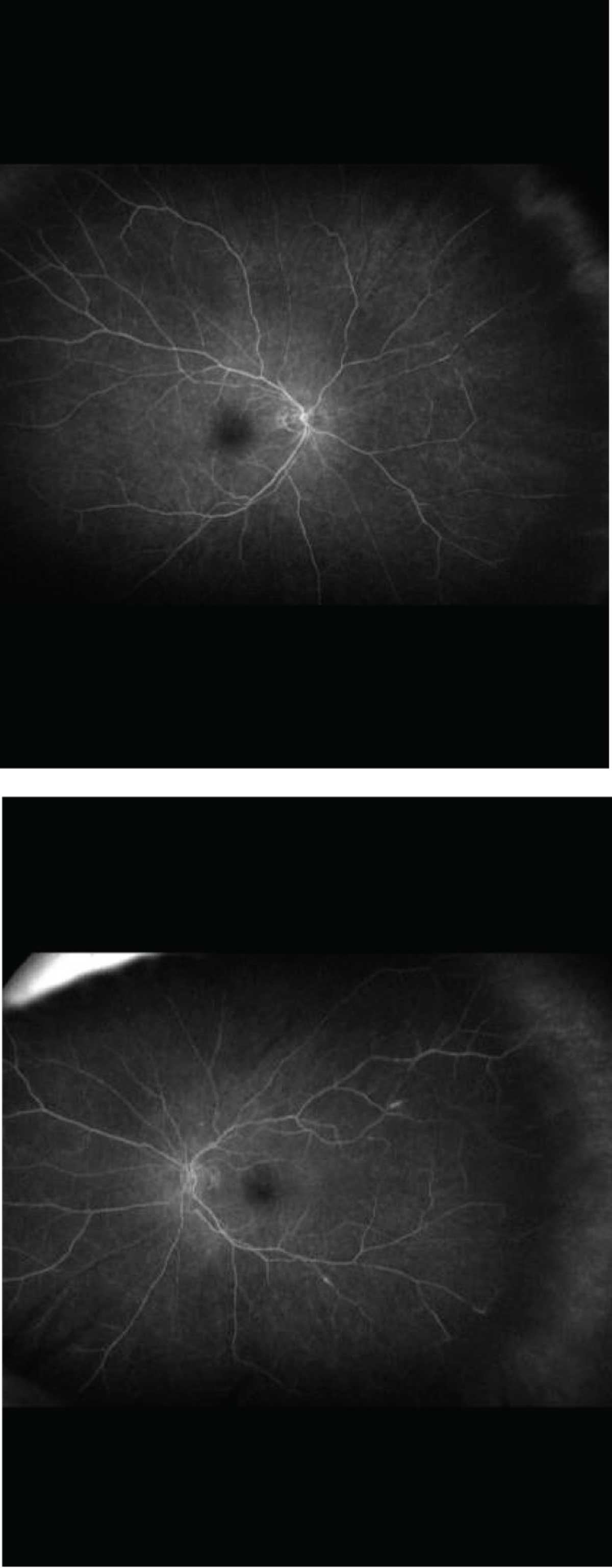

Fluorescein angiogram showed mildly delayed arterial-venous transit time and peripheral nonperfusion OU. The left eye demonstrated a few small focal areas of periarterial leakage (Figure 4). Full-field electroretinogram (ERG) was isoelectric in the scotopic, combined flash, single flash photopic and 30-hertz flicker stimuli, consistent with marked rod and cone dysfunction. Humphrey visual field 24-2, Stim V revealed diffuse depression OU.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbits with and without contrast was within normal limits.

|

| Figure 1. Color photography demonstrated marked arterial and venous sheathing in both eyes. |

Additional history and diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with endometrial adenocarcinoma in October 2020. She received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel with surgical resection in March 2021. In May 2021, the patient received one cycle of pembrolizumab.

Given the patient’s medical history and imaging findings, we diagnosed cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR).

|

| Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography showed marked loss of the ellipsoid zone outside the foveal center as well as significant loss of laminations of the outer plexiform and outer nuclear layers. |

Follow-up

The patient received sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone injections in both eyes and was started on prednisolone acetate q.i.d. After discussion with her oncologist, she was started on prednisone 60 mg PO daily with calcium/vitamin D supplementation.

At two-week follow-up, the patient’s VA declined to 20/200 OU. We discussed

escalating immunotherapies, including rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) and plasmapheresis (Plex) with her oncologist. The patient received five treatments of Plex on an every-other-day basis, followed by four weekly rituximab infusions.

VA at a three-month follow-up improved to 20/30 OD and 20/50 OS. However, at the four-month follow-up, the patient noted subjective decreased vision with a visual acuity of 20/50 OD and 20/70 OS. She received another course of Plex and rituximab. Unfortunately on follow-up one month later, her VA declined to light perception OU.

|

|

Figure 3. Fundus autofluorescence revealed hyperautofluorescence of the posterior pole with mottled areas of hypoautofluorescence throughout the macula as well as perivascular hyperautofluorescence in both eyes. |

Features of CAR

CAR is one member of a spectrum of autoimmune retinopathies. This spectrum can be divided into neoplastic and non-neoplastic entities. Neoplastic entities include CAR and melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR). CAR was first described by Ralph Sawyer, MD, and colleagues in 1976.1 The pathogenesis of CAR occurs when tumor-associated antigens trigger production of autoantibodies that cross-react with retinal antigens, leading to retinal degeneration.2

|

CAR affects women twice as frequently as men, whereas MAR more commonly affects men.3 Patients are most commonly affected in their fifth or sixth decade of life.

Small-cell carcinoma is the most commonly associated malignancy, followed by breast, uterine and cervical carcinoma.4 The interval between diagnosis of malignancy and onset of visual symptoms varies. Visual symptoms typically precede the cancer diagnosis. Antirecoverin and antienolase antibodies are among the most frequently identified autoantibodies.5 Recoverin is a protein present in photoreceptors involved in light and dark adaptation. Antienolase antibodies have been associated with breast and prostate cancer.6

Patients typically present with bilateral, subacute vision loss, scotomas, photopsias and nyctalopia.7 There’s no consensus on diagnostic criteria. The presence of autoimmune retinal antibodies isn’t required, nor is it diagnostic, because they can be present in unaffected patients.

Fundus autofluorescence imaging can show stippled hyperautofluorescence in the posterior pole. Spectral-domain OCT commonly shows outer retinal loss and ellipsoid disruption.2 Cystoid macular edema is also present in some cases. Full-field ERG can show variable abnormalities, depending on the degree of cone vs. rod function. Visual-field testing shows central or paracentral scotomas and constriction.2

|

| Figure 4. Fluorescein angiogram showed mildly delayed arterial-venous transit time and peripheral nonperfusion. The left eye (bottom) demonstrated a few small focal areas of periarterial leakage. |

Treatment

Visual deterioration in CAR can be severe. No standard treatment protocol exists. Treatment options include immunosuppression via systemic or local corticosteroids, including sub-Tenon’s and intravitreal forms, as well as immunomodulatory therapy, including IVIg, plasmapheresis, cyclosporin, rituximab, infliximab, azathioprine and tocilizumab.6

The clinical course and therapy response are highly variable. Paramount in the discovery of CAR is a thorough systemic work-up and identification of the primary malignancy. Care of the retinopathy should be carefully coordinated with the patient’s primary care physician and/or oncologist.

Bottom line

CAR is one entity in a complex category of autoimmune retinopathies that can have widely variable presentations. Careful examination in conjunction with ancillary testing is crucial for proper diagnosis. Comanagement with the patient’s primary care physician and oncologist is important to minimize morbidity and mortality. RS

REFERENCES

1. Sawyer RA, Selhorst JB, Zimmerman LE, Hoyt WF. Blindness caused by photoreceptor degeneration as a remote effect of cancer. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;81:606-613.

2. Dutta Majumder P, Marchese A, Pichi F, Garg I, Agarwal A. An update on autoimmune retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:1829-1837.

3. Adamus G, Ren G, Weleber RG. Autoantibodies against retinal proteins in paraneoplastic and autoimmune retinopathy? BMC Ophthalmol. 2004;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-4-5.

4. Dot C, Guigay J, Adamus G. Anti-alpha-enolase antibodies in cancer-associated retinopathy with small cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:746–747.

5. Shildkrot Y, Sobrin L, Gragoudas ES. Cancer-associated retinopathy: Update on pathogenesis and therapy. Sem Ophthalmol. 2011;26:321-328.

6. Grewal DS, Fishman GA, Jampol LM. Autoimmune retinopathy and antiretinal antibodies: A review. Retina. 2014;34:827-845.

7. Grange L, Dalal M, Nussenblatt RB, Sen HN. Autoimmune retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:266–272.