|

|

Bios Dr. Tsui is an assistant professor of ophthalmology in the uveitis service at the Jules Stein Eye Institute, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Shusko has no financial disclosures. Dr. Tsui is a consultant for Kowa Company and EyePoint Pharmaceuticals. |

Oncologic immunotherapies continue to be developed and transform the management choices of multiple types of cancer. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are a class of immunotherapy that disinhibits T-cells to promote the detection and elimination of abnormal host cells. The aim is to increase the antitumor response, but they also may cause systemic and ocular autoimmune side effects known as immune-related adverse events, or IRAEs.

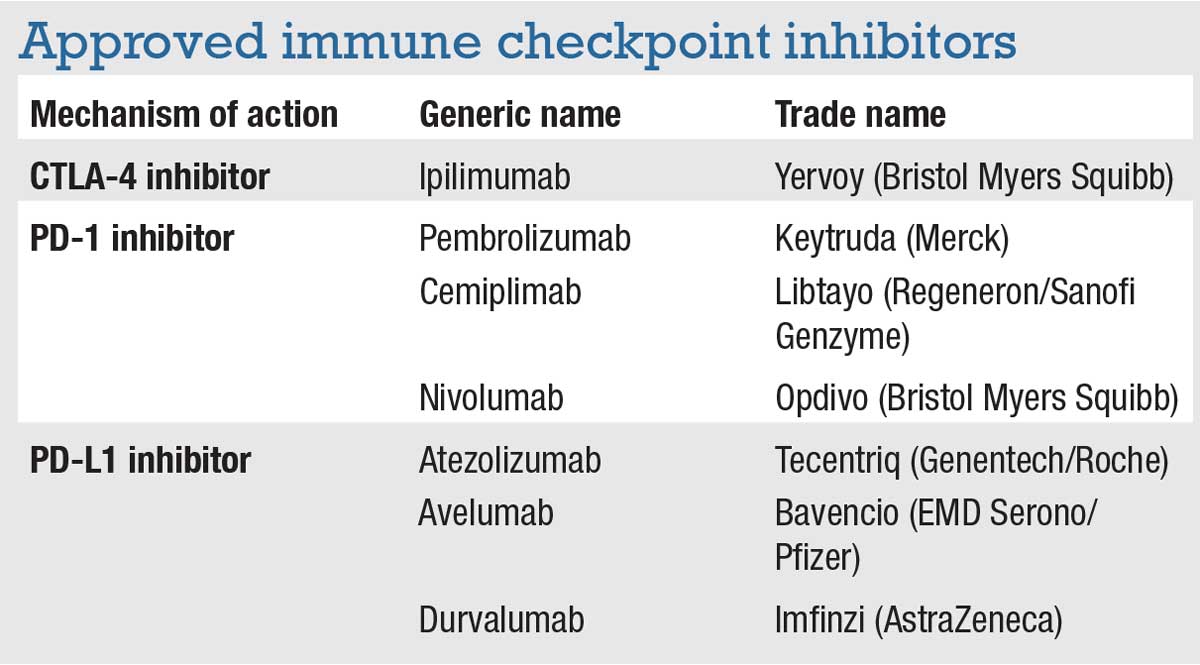

There are seven approved immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPIs) in the United States (Table). These medications target three different checkpoints:

- cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4);

- programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1); and

- programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1).

ICPIs are used for many types of cancers, but primarily for metastatic melanoma. Off-label uses for other types of cancers are starting to emerge as ICPIs become more widely available.

Ocular IRAEs

IRAEs in the eye most commonly affect the ocular surface, manifesting as conjunctivitis, episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis, corneal graft rejection and dry-eye syndrome.1,2 Orbital complications include myasthenia gravis, exacerbation of thyroid ophthalmopathy, thyroid-like ophthalmopathy, cranial nerve palsies and myopathy.

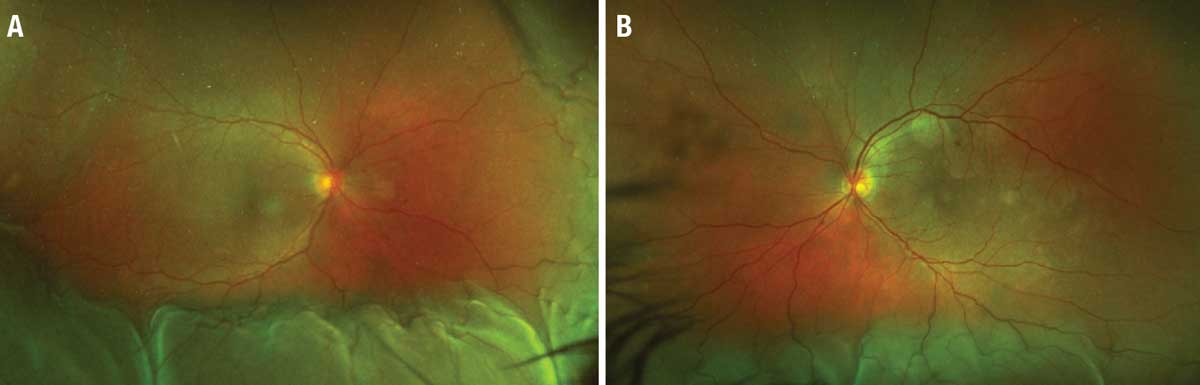

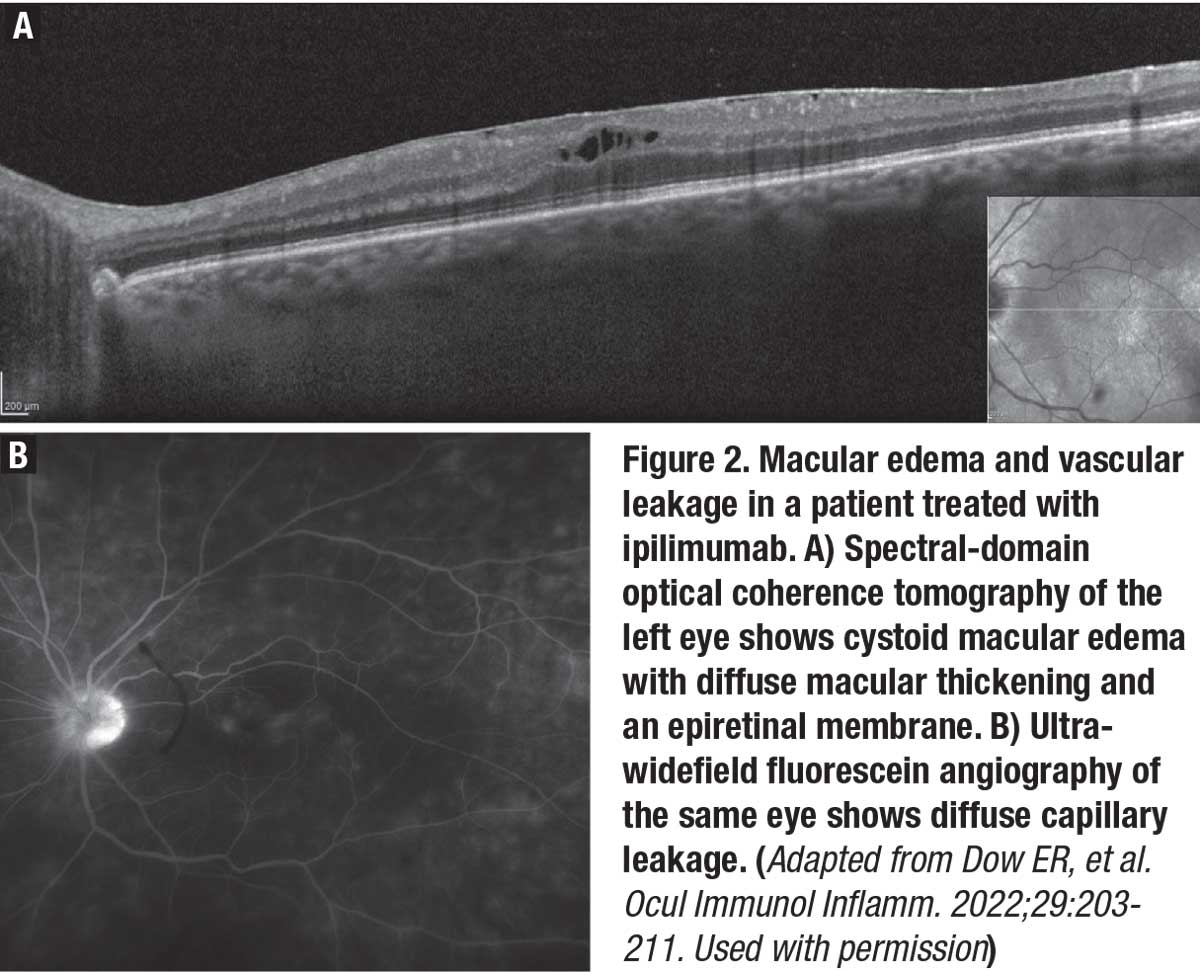

ICPI-associated uveitis (ICPIU) is becoming more recognized with the increasing publication of case reports and case series. Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate examples of uveitis in patients undergoing treatment with ICPIs. The incidence of IRAEs with use of ICPIs was 1.2 percent in a large database study.3 These authors noted a higher rate of ICPIU in patients with melanoma than other types of cancer.

ICPIU was more common with CTLA-4 inhibitors (ipilimumab) than other medication classes. Patients with a history of uveitis had higher rates of ICPIU. Patients affected by ICPIU were disproportionately Caucasian (82 percent), a disparity that may be due to the high prevalence of melanoma, the most common indication for ICPIs, in Caucasians.4,5

|

| Figure 1. Posterior uveitis with choroidal effusions in a patient treated with a ipilimumab-nivolumab combination. A) Ultra-widefield color fundus photograph of the right eye shows choroidal effusion inferiorly, nasally, and temporally as well as subretinal fluid in the macula. B) Color photograph of the left eye also reveals an inferior choroidal effusion and macula-involving subretinal fluid. (Adapted from Dow ER, et al. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2022;29:203-211. Used with permission) |

Characteristics of ICPIU

A literature review last year of 126 ICPIU cases reported that anterior uveitis was the most common type (37.7 percent) followed by panuveitis (34 percent) and posterior uveitis (25.7 percent).6 Intermediate uveitis (0.01 percent) was rarely reported. Most ICPIU cases followed these distribution patterns except in two cases.

Combination ipilimumab/nivolumab had an increased incidence of anterior uveitis (52.8 percent). Atezolizumab had no incidence of anterior uveitis, but it did have increased rates of posterior uveitis (80 percent). More specifically, IRAEs associated with atezolizumab were described as resembling acute macular neuroretinopathy (AMN) or paracentral acute middle maculopathy (PAMM) with retinal vasculitis or venulitis. No other ICPIs had a presentation like AMN or PAMM.

|

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada-like disease was seen in 35 percent of patients who presented with panuveitis. The association between VKH disease and melanoma has been well-described.7-11 An analysis of 48 cases of ICPIU presenting as VKH-like posterior inflammation showed the most common cancer association was melanoma (79 percent).12

Forty-four percent of VKH-like cases were associated with pembrolizumab, 23 percent with ipilimumab and 17 percent with nivolumab. Cases of VKH-like panuveitis were noted to have prodromal malaise and headache, serous retinal detachments, hearing loss, vitiligo and/or poliosis. Cross-reactivity between retinal and melanoma antigens may play a role in ICPIU.

Risk factors and management

A literature review of 40 patients found that the primary indication for ICPIs was lung cancer,12 countering the studies that stated melanoma was the primary association. Patients with a history of ocular trauma, ocular surgery or use of pembrolizumab were more likely to experience intraocular inflammation.

|

Currently, the literature on ICPIU consists of only case reports, case series and survey studies. No standard recommendation exists for treatment of ICPIU.

The most common treatment uses topical steroids. In a review of 49 ICPIU cases, 27 patients received topical steroids only, with resolution of the uveitis in most cases.13 Topical steroids used included prednisolone acetate 1% and difluprednate 0.05%. Dosing frequency ranged from q.i.d. to hourly. Nine cases were treated with periocular steroid injections with or without topical steroids; the results were similar. Triamcinolone and dexamethasone were the most used periocular injections.

Thirteen patients received oral or intravenous steroids along with local therapy. The indication for initiating systemic steroids was ICPIU in eight of the 13 cases. ICPIs were discontinued in 18 cases, but only nine of them were due to ICPIU.

One case of nivolumab-associated ICPIU that was successfully treated with frequent topical steroids developed CME that required intravitreal triamcinolone.14 The patient required an additional intravitreal triamcinolone treatment eight months after discontinuation of nivolumab. Cases have reported methotrexate use, but very few reports of steroid-sparing immunomodulatory agents for the treatment of ICPIU have been published.11

Framework for treatment

A recently published case series with a review of guidelines from the European Society of Medical Oncology and American Society of Clinical Oncology provides a framework for ICPIU treatment.15 They reported eight cases of ocular IRAEs, including five cases of anterior uveitis and one of intermediate uveitis.

|

Each case of anterior uveitis was successfully managed with topical steroids alone while the patients continued ICPI treatment. The case of intermediate uveitis required oral prednisone and discontinuation of pembrolizumab. The patient was rechallenged with ipilimumab but had to abort therapy after two cycles due to severe colitis. The patient’s metastatic disease had remained stable for 14 months at the time of publication.

Patients on ICPIs who experience ocular symptoms should be referred to an ophthalmologist early for further testing to grade the severity of the IRAEs. Both treatment of uveitis and ICPI use should be evaluated on an individual patient basis. Often, depending on the severity of the inflammation, local therapy may be sufficient to control it without stopping ICPI or using systemic corticosteroids. A multidisciplinary approach to managing ocular IRAEs should be weighed with the benefit of continuing the ICPI therapies.

Bottom Line

We’re learning more about the immune- related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors as case reports and case series emerge. Ocular side effects most commonly involve the ocular surface, but ICPIU is a concern for patient morbidity.

Depending on the severity and response of the uveitis, topical or systemic steroids may be sufficient while continuing the ICPI. Any decision to suspend or discontinue ICPIs must involve the oncologist and ophthalmologist because these drugs may extend patient survival. RS

REFERENCES

1. Dalvin L, Shields CL, Orloff M, Sato T, Shields JA. Checkpoint inhibitor immune therapy. Retina. 2018;38:1063-1078.

2. Sun MM, Levinson RD, Filipowicz A, et al. Uveitis in patients treated with CTLA-4 and PD-1 checkpoint blockade inhibition. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28:217-227.

3. Braun D, Getahun D, Chiu VY, et al. Population-based frequency of ophthalmic adverse events in melanoma, other cancers, and after immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;224:282-291.

4. Luiz OC, Gianini RJ, Gonçalves FT, et al. Ethnicity and cutaneous melanoma in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil: A case-control study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36348.

5. Raimondi S, Suppa M, Gandini S. Melanoma epidemiology and sun exposure. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00136. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3491.

6. Dow ER, Yung M, Tsui E. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated uveitis: Review of treatments and outcomes. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:203-211.

7. Norose K, Yano A. Melanoma specific Th1 cytotoxic T lymphocyte lines in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:1002-1008.

8. Lavezzo MM, Sakata VM, Morita C, et al. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: Review of a rare autoimmune disease targeting antigens of melanocytes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:29.

9. Shi T, Lv W, Zhang L, Chen J, Chen H. Association of HLA-DR4/HLA-DRB1∗04 with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6887.

10. Wong RK, Lee JK, Huang JJ. Bilateral drug (Ipilimumab)-induced vitritis, choroiditis, and serous retinal detachments suggestive of Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada Syndrome. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2012;6: 423-426.

11. Matsuo T, Yamasaki O. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease-like posterior uveitis in the course of nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antibody), interposed by vemurafenib (BRAF inhibitor), for metastatic cutaneous malignant melanoma. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5:694-700.

12. Kim YJ, Lee JS, Lee J, et al. Factors associated with ocular adverse event after immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69:2441-2452.

13. Venkat AG, Arepalli S, Sharma S, et al. Local therapy for cancer therapy-associated uveitis: A case series and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:703-711.

14. Richardson DR, Ellis B, Mehmi I, Leys M. Bilateral uveitis associated with nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma: A case report. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10:1183-1186.

15. Shahzad O, Thompson N, Clare G, Welsh S, Damato E, Corrie P. Ocular adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A novel multidisciplinary management algorithm. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:1758835921992989. doi:10.1177/1758835921992989.