|

Bios Dr. Leveque is a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Washington in Seattle where Dr. Hashimi is an ophthalmology resident and Dr. Agi is a retina fellow. DISCLOSURES: The authors have no relevant disclosures. |

Presentation

A 33-year-old male was referred to our tertiary care hospital for ophthalmic evaluation of transient vision loss in both eyes. The patient was in his usual state of good health but developed a sore throat, fever, chills and full body aches prior to presentation. He tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) and was treated with azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin. Four days later, he experienced episodic periods of dizziness, arm numbness, headaches, tinnitus and bilateral vision loss.

Examination Findings

During the initial presentation to an outside emergency room, he underwent an immediate stroke protocol work-up, including MRI of the brain, which demonstrated multifocal small infarcts. Laboratory testing was unremarkable, but ultrasound of the lower extremities revealed a unilateral deep vein thrombosis, for which he was started on a heparin drip. Unfortunately, his encephalopathy progressed with worsening confusion and seizures, so he underwent repeat MRI which showed a concomitant increase in the number of infarcts, localizing around the corpus callosum. CT angiogram, however, didn’t show occlusion or vascular anomalies.

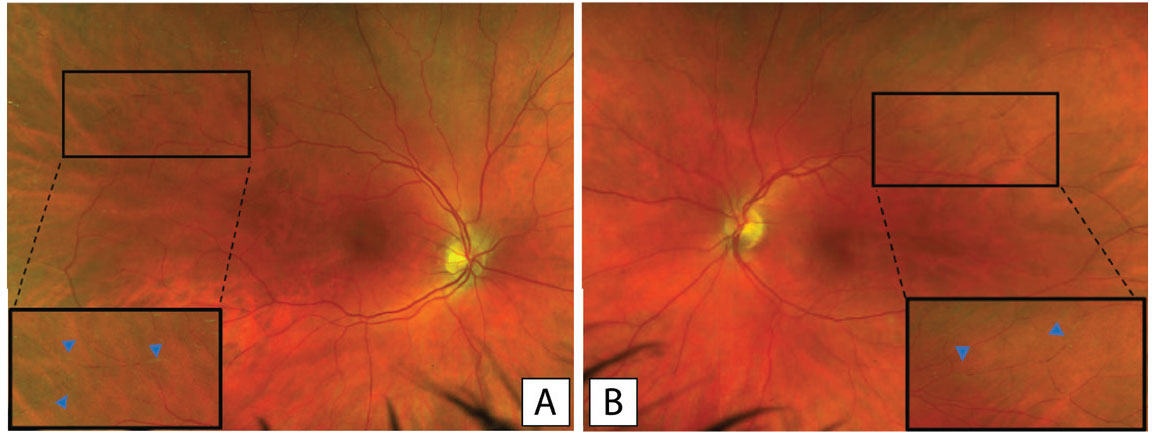

In the setting of his episodic vision loss, the patient was transferred to our center for ophthalmic evaluation. At that time, the patient’s best corrected Snellen visual acuity had improved to 20/20 bilaterally with normal eye pressures and no afferent pupillary defect. He didn’t have any signs of anterior or intermediate uveitis, but dilated fundus exam revealed bilateral sectoral arterial box-caring and Gass plaques (GPs) in the temporal and superior quadrants (Figure 1).

Work-up

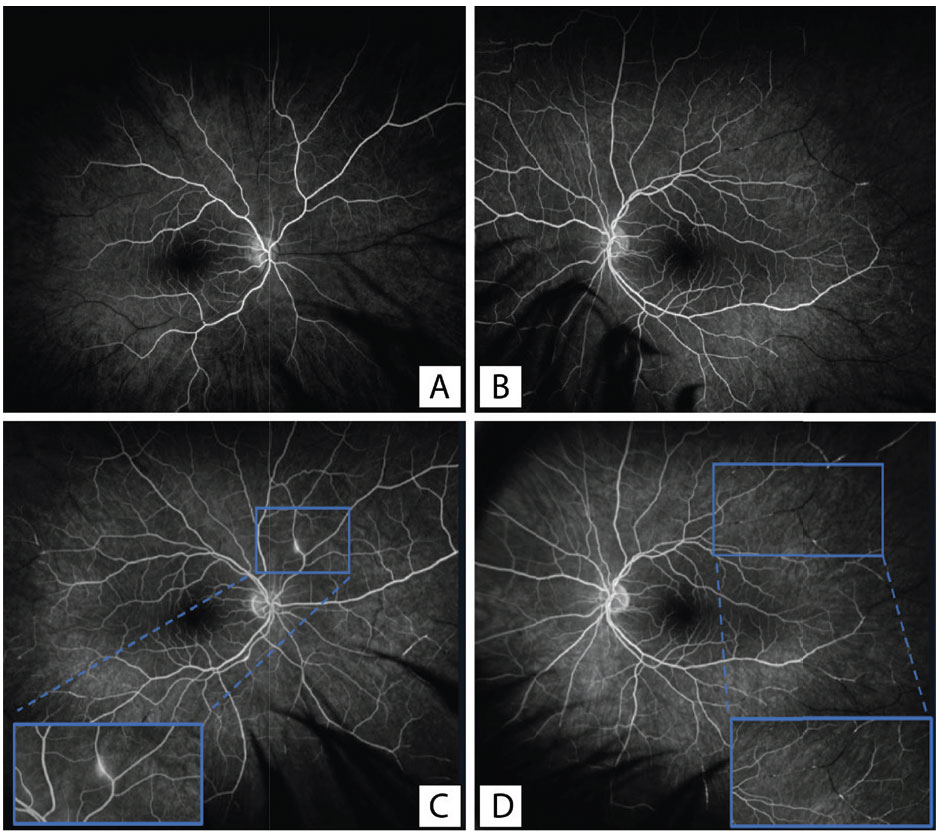

To further evaluate the retinal changes, we obtained widefield fluorescein angiography with transit of the right eye (Figure 2). There was a normal arm-to-eye time of 11 seconds, but later frames demonstrated multiple branch retinal artery occlusions and peripheral non-perfusion in the temporal retina bilaterally. There was also perivascular leakage in the superonasal mid-periphery of the right eye. Given his retinal findings and tinnitus, the patient also underwent audiology testing, which confirmed moderately-severe sensorineural hearing loss.

|

|

Figure 1. Pseudocolor fundus photography of the right (A) and left (B) eyes respectively with a magnified view showing bilateral artery attenuation and arrows pointing to the Gass plaques. |

Diagnosis and Management

The patient was diagnosed with Susac Syndrome given the complete triad of encephalitis, branch retinal artery occlusions and sensorineural hearing loss.

The mainstay of treatment is immunosuppression to mitigate the auto-immune mediated inflammatory response. Our patient was started on five days of high-dose IV methylprednisolone 1,000 mg/day for CNS vasculitis. The neurology team initiated intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for three days before transitioning to Rituximab 1,000 mg every six months with a slow taper off high-dose oral steroids.

Given the extent of peripheral retinal ischemia, he was seen in the Retina Department for pan retinal photocoagulation of the areas of non-perfusion as prophylaxis against neovascularization. He has subsequently followed in the Uveitis Department for monitoring for re-activation as he tapered off oral steroids.

Discussion

Susac Syndrome (SuS) is an idiopathic systemic vasculitis presumed to be due to an immune-mediated inflammation of the vascular endothelium presenting clinically as a triad of central nervous system dysfunction, branch retinal artery occlusion and sensorineural hearing loss. It most commonly occurs in the second to fourth decades of life. While typically a single episode, recurrences have been reported in up to 42 percent of cases.1

|

|

Figure 2. Optos fluorescein angiography demonstrating multiple peripheral retinal artery occlusions with associated peripheral non-perfusion. Frames A and B demonstrate early phase filling of the right and left eye, respectively. Frame C demonstrates a magnified view of the arterial wall hyperfluorescence, which can be observed in the peripheral vasculature, most significantly in the superonasal quadrant. Panel D demonstrates late filling of the left eye with a magnified view of multiple retinal artery occlusions in the vascular periphery. |

While our patient presented with all three symptoms in rapid succession, SuS can be difficult to diagnose, as the triad is usually incomplete at disease onset. Diagnostic criteria are divided into definite and probable SuS based on constellations of clinical symptoms and diagnostic signs.2 Brain MRI findings include multifocal hyperintense round small lesions, typically involving the corpus collosum. In the eye, in addition to multiple branch retinal artery occlusions, other exam findings may aid with diagnosis including Gass plaques. Initially described by Don Gass,3 GPs are small yellow or yellow-white plaques located along the lumen of vessels, and frequently occur away from arteriolar bifurcations, which can help differentiate them from Hollenhorst plaques. While GPs are not unique to Susac Syndrome, they are a common feature and should be differentiated from other types of plaques.

Fluorescein angiography can also be a helpful modality for diagnosis and treatment. Typical findings were reported in 2007,4 including GPs and arterial wall hyperfluorescence (AWH), which can also be seen in the case presented here (Figure 2). In addition, the FA can be useful to evaluate areas of non-perfusion and neovascularization, which may guide preventative treatment with PRP.

Interestingly, our patient developed SuS shortly following a COVID-19 infection, which is known to be associated with systemic vasculitis5 and retinal microvascular occlusions.6 The unique clinical and diagnostic findings in our patient confirmed a named SuS diagnosis. To date, a few cases of SuS occurring following COVID-19 infection have been reported in the literature,7,8 although the high prevalence of COVID-19 infection in the general population and the rarity of SuS precludes us from drawing definitive conclusions about causation.

This case serves as a reminder that seemingly routine diagnoses such as artery occlusions require a high level of suspicion with a carefully obtained history and review of systems, which may help guide the workup and aid in revealing an underlying diagnosis. RS

REFERENCES

1. Dörr J, Krautwald S, Wildemann B, et al. Characteristics of Susac syndrome: A review of all reported cases. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:6:307-316.

2. Kleffner I, Dörr J, Ringelstein M for the European Susac Consortium (EuSaC), et al. Diagnostic criteria for Susac syndrome Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2016;87:1287-1295.

3. Gass JDM, Tiedeman J, Thomas MA. Idiopathic recurrent branch retinal arterial occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:9:1148-1157.

4. Martinet N, Fardeau C, Adam R, et al. Fluorescein and indocyanine green angiographies in Susac syndrome. Retina. 2007;27:9:1238-1242.

5. Wong K, Shah MUFA, Khurshid M, Ullah I, Tahir MJ, Yousaf Z. COVID-19 associated vasculitis: A systematic review of case reports and case series. Ann Med Surg. 2022;74:103249.

6. Fonollosa A, Hernández-Rodríguez J, Cuadros C, et al. Characterizing COVID 19-related retinal vascular occlusions: A case series and review of the literature. Retina. 2022;42:3:465-475.

7. Raymaekers V, D’hulst S, Herijgers D, et al. Susac syndrome complicating a SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Neurovirol. Published online 2021:1-6.

8. Venditti L, Rousseau A, Ancelet C, Papo T, Denier C. Susac syndrome following COVID-19 infection. Acta Neurol Belg. 2021;121:807-809.