|

|

Bios Dr. Suhler is a professor of ophthalmology at OHSU. Dr. Thomas is an associate in vitreoretinal surgery and uveitis at Tennessee Retina, with offices in central Tennessee and southern Kentucky. DISCLOSURES: Drs. Suresh, Suhler and Thomas have relevant financial relationships to disclose. |

The treatment of noninfectious uveitis has long relied on the use of systemic immunosuppression, most commonly with first-line antimetabolite immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil, and with off-label biologics for refractory patients.

|

|

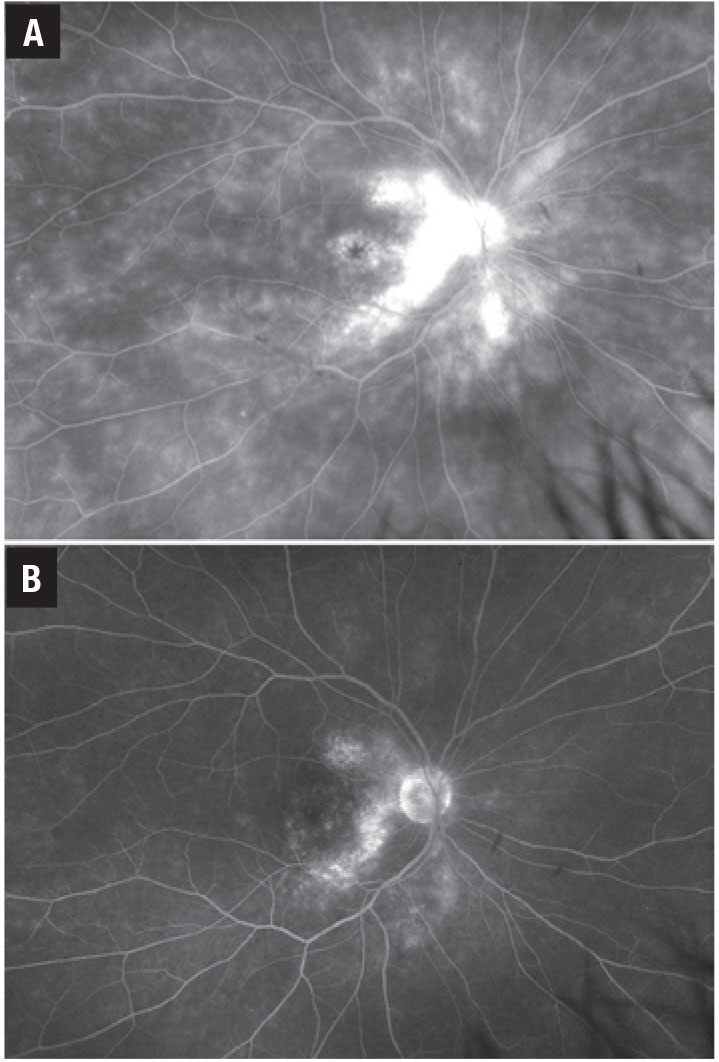

Figure 1. Vascular leakage in sarcoid retinal vasculitis on adalimumab 40 mg every two weeks (A) and after transitioning to tocilizumab 162 mg every two weeks (B). |

In 2016 the biologic tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) became the first and only Food and Drug Administration-approved non-corticosteroid treatment for noninfectious uveitis in adults. That approval was based on the results of two large multicenter randomized clinical trials, VISUAL 1 and 2,1 and extended to children after the SYCAMORE study.2 Since the approval of adalimumab, the field of anti-inflammatory biologics has rapidly progressed, and multiple additional agents have been or are being investigated for the treatment of uveitis. We review them here.

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

TNF inhibitors are the most broadly utilized and effective class of biologics for the treatment of uveitis, and adalimumab remains the most widely used. Standard adalimumab dosing is a subcutaneous injection of 40 mg every two weeks after a loading dose of 80 mg followed by 40 mg one week later; loading doses are deferred in children.

Although highly effective, about 40 to 60 percent of patients on this regimen will develop treatment failure at one year, according to the VISUAL I and II studies.1 Treatment failure can often be attributed to the development of anti-adalimumab neutralizing antibodies, although insufficient serum levels of adalimumab, or simply non-responsiveness to TNF blockade can also contribute. Testing for the presence of serum anti-adalimumab antibodies can help guide treatment decisions in cases of loss of response. If anti-adalimumab antibodies are absent, increasing the serum level of adalimumab by switching to weekly dosing has been shown to improve uveitis control in about 60 percent of patients.3

Five alternative TNF inhibitors

Alternatively, the presence of anti-adalimumab antibodies might prompt a switch to an alternative TNFi rather than escalation to weekly therapy. Currently four FDA-approved alternative TNFis exist: infliximab (Remicade, Janssen); golimumab (Simponi, Janssen); certolizumab pegol (Cimzia, UCB); and etanercept (Enbrel, Amgen).

• Infliximab. Of the alternatives, this is the most-studied TNFi in uveitis. The efficacy of infliximab for the treatment of uveitis is likely similar to that of adalimumab.4,5 Unlike adalimumab, which is a fully human monoclonal antibody, infliximab is a chimeric human/mouse antibody leading to a higher immunogenicity and greater risk of forming anti-drug antibodies. For this reason, many practitioners recommend concurrent use of an antimetabolite to reduce antibody formation.

The primary advantage of infliximab over adalimumab is the potential to achieve higher therapeutic levels. Infliximab is given as an intravenous infusion administered with three loading infusions over six weeks, followed by infusions at four-to-eight-week intervals at doses of 5 to 20 mg/kg.

• Golimumab. This humanized antibody can be administered as a subcutaneous injection every four weeks or as an intravenous infusion (Simponi Aria) every four to eight weeks. Although literature on its use in uveitis is still fairly limited, a few studies have shown a promising response for uveitis refractory to both adalimumab and infliximab.6,7

• Certolizumab pegol. This uniquely constructed agent uses a humanized anti-TNF Fab fragment joined with a polyethylene glycol molecule in place of the Fc fragment. The lack of an Fc fragment is thought to reduce the immunogenicity compared to other TNF inhibitors. Also, the lack of an Fc fragment prevents placental transfer of certolizumab, making it the safest TNFi to use in pregnancy.8 Like golimumab, the available data on its efficacy in ocular inflammation is sparse, although it has shown promising results in treating patients refractory to multiple other TNFi.9

• Etanercept. A recombinant fusion protein composed of the TNF receptor and the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G1, etanercept is used extensively in rheumatoid arthritis. It’s widely considered ineffective for uveitis and may even induce paradoxical flares of uveitis.10

Interleukin-6 inhibitors

|

|

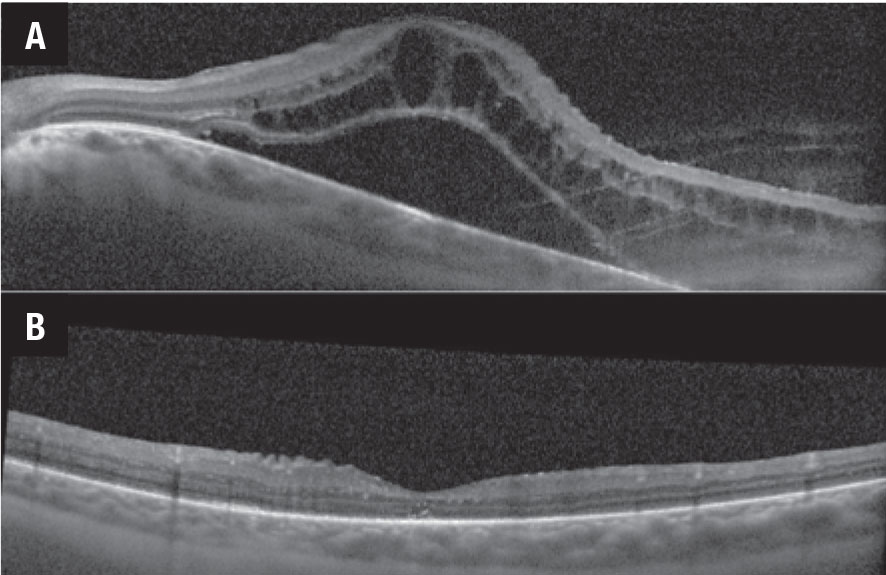

Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography scans demonstrate macular edema before (A) and after (B) intravenous tocilizumab therapy. |

Another class of drugs includes tocilizumab (Actemra, Genentech), a humanized interleukin-6 inhibitor that can be administered subcutaneously every one to two weeks or as an IV infusion every four weeks. It’s currently approved for the treatment of RA, giant cell arteritis and some forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Although highly effective in select cases of uveitis, IL-6 inhibition likely has a much narrower role in the treatment of ocular inflammatory disease than the TNFi.

The APTITUDE trial evaluating tocilizumab in TNFi-refractory JIA uveitis failed to meet its primary endpoint of inflammatory control, although about 30 percent of patients showed improvement when switched from a TNFi to tocilizumab.11 Tocilizumab does appear to be effective for the treatment of retinal vascular leakage, with 83 percent of patients showing improvement in angiographic inflammation (Figure 1).12 Tocilizumab has also proven to be highly effective in the treatment of uveitic macular edema, with early studies showing a dramatic response to treatment (Figure 2).13

Sarilumab (Kevzara, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) is an alternative to IL-6 inhibition. It has similarly shown efficacy in posterior segment disease, particularly uveitic macular edema.14

CD-20 inhibitors

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody against the CD-20 antigen found on B-lymphocytes. Administered as an IV infusion every six to 12 months, rituximab leads to a depletion of the B-cell population. Compared with the other biologics, the long-lasting effect of rituximab increases its immunosuppressive risk. Although effective in the treatment of orbital inflammatory disease, recurrent scleritis and severe JIA uveitis, the utility of rituximab in treating other forms of uveitis has been fairly limited.15 As a result, rituximab is often relied on only in severe disease recalcitrant to other forms of treatment.

Other anti-inflammatory biologics

A number of biologics targeting alternative cytokines have been explored as potential therapeutics for uveitis. Some of these agents include inhibitors of IL-1 (anakinra, canakinumab), IL-2 (daclizumab), IL-17 (ixekizumab, secukinumab) and IL-23 (ustekinumab, guselkumab).

Currently, the utility of most of these agents for the treatment of uveitis is largely anecdotal and limited to case reports. Secukinumab is the only agent that has been evaluated in a clinical trial for the treatment of uveitis. However, results of this trial were mixed, with patients receiving intravenous secukinumab dosed at 30 mg/kg every four weeks showing a 73-percent response rate, although remission at 57 days was reported in only 27 percent of patients.16 A clinical trial investigating ustekinumab for the treatment of Behçet’s uveitis is under way.17

Bottom line

Adalimumab remains the mainstay of treatment for uveitis refractory to antimetabolite therapy. In cases of adalimumab failure, switching to a newer TNFi such as golimumab and certolizumab may provide inflammatory control. On the other hand, the IL-6 inhibitors tocilizumab and sarilumab provide an alternative treatment option and appear to be particularly effective when used in cases where uveitic macular edema and retinal vasculitis are predominant manifestations of disease. Rituximab has been shown to be effective in select cases of refractory scleritis, orbital inflammatory disease and JIA-associated uveitis. The optimal use of other targeted biologic anti-inflammatory agents in the treatment of uveitis is yet to be fully elucidated. RS

REFERENCES

1. Sheppard J, Joshi A, Betts KA, et al. Effect of adalimumab on visual functioning in patients with noninfectious intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, and panuveitis in the VISUAL-1 and VISUAL-2 trials. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:511-518.

2. Horton S, Jones AP, Guly CM, et al. Adalimumab in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: 5-year follow-up of the Bristol participants of the SYCAMORE Trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;207:170-174.

3. Lee J, Koreishi AF, Zumpf KB, Minkus CL, Goldstein DA. Success of weekly adalimumab in refractory ocular inflammatory disease. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:1431-1433.

4. Martel JN, Esterberg E, Nagpal A, Acharya NR. Infliximab and adalimumab for uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2012;20;18-26.5. Vallet H, Seve P, Biard L, et al. Infliximab versus adalimumab in the treatment of refractory inflammatory uveitis: A multicenter study from the French Uveitis Network. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1522-1530.

6. Fabiani C, Sota J, Rigante D, et al. Rapid and sustained efficacy of golimumab in the treatment of multirefractory uveitis associated with Behçet’s disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27:58-63.

7. Miserocchi E, Modorati G, Pontikaki I, Meroni PL, Gerloni V. Long-term treatment with golimumab for severe uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22:90-95.

8. Prieto-Peña D, Calderón-Goercke M, Adán A, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol in pregnant women with uveitis. Recommendations on the management with immunosuppressive and biologic therapies in uveitis during pregnancy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39:105-114.

9. Llorenç V, Mesquida M, Sainz De La Maza M, et al. Certolizumab pegol, a new anti-TNF-α in the armamentarium against ocular inflammation. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24:167-72

10. Ferreira LB, Smith AJ, Smith JR. Biologic drugs for the treatment of noninfectious uveitis. Asia-Pacific J Ophthalmol (Phila.). 2021;10:63-73

11. Ramanan A V., Dick AD, Guly C, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with anti-TNF refractory juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (APTITUDE): A multicentre, single-arm, Phase 2 trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e135-e141.

12. Sadiq MA, Hassan M, Afridi R, et al. Posterior segment inflammatory outcomes assessed using fluorescein angiography in the STOP-UVEITIS study. Int J Retin Vitr. Published online October 6, 2020.

13. Mesquida M, Molins B, Llorenç V, et al. Twenty-four month follow-up of tocilizumab therapy for refractory uveitis-related macular edema. Retina. 2018;38:1361-1370.

14. Heissigerová J, Callanan D, de Smet MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of sarilumab for the treatment of posterior segment noninfectious uveitis (SARIL-NIU): The Phase 2 SATURN study. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:428-437.

15. Miserocchi E, Pontikaki I, Modorati G, Gattinara M, Meroni PL, Gerloni V. Anti-CD 20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) treatment for inflammatory ocular diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;11:35-39.

16. Letko E, Yeh S, Stephen Foster C, Pleyer U, Brigell M, Grosskreutz CL. Efficacy and safety of intravenous secukinumab in noninfectious uveitis requiring steroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:939-948.

17. Pepple KL, Lin P. Targeting interleukin-23 in the treatment of noninfectious uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:1977-1983.