|

|

Bio Dr. Yonekawa is an adult and pediatric retina specialist at Wills Eye Hospital/Mid |

The 11th Vit Buckle Society annual meeting in Las Vegas, Nevada, brought engaging, informative and spirited surgical discussion to the stage by a host of expert surgeons. Here, we provide summaries of five standout surgical talks.

As more treatments emerge, understanding the natural progression of GA and the baseline characteristics that predict progression will help us to choose the optimal strategy. Here, we report on recent literature into the natural progression of GA, the rate of progression, interventions to slow its progression and the ultimate implications of untreated GA.

Pediatric retina surgery tips

By Hong-Uyen Hua, MD

|

|

Dr. Hua is a second-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow at the Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute. DISCLOSURE: Dr. Hua disclosed relationships with Alimera Sciences, AbbVie/Allergan and Genentech/ Roche. |

|

Pediatric retina surgery can be intimidating, but J. Peter Campbell, MD, distilled a few basic principles for these potentially challenging operations. Dr. Campbell is the Edwin and Josephine Knowles Professor at Casey Eye Institute at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland.1

He elucidated essentials for fixing pediatric tractional retinal detachments: an understanding of the anatomy; and to get out of the eye as quickly and as safely as possible after achieving the surgical goal. Dr. Campbell demonstrated these principles with a few surgical case studies.

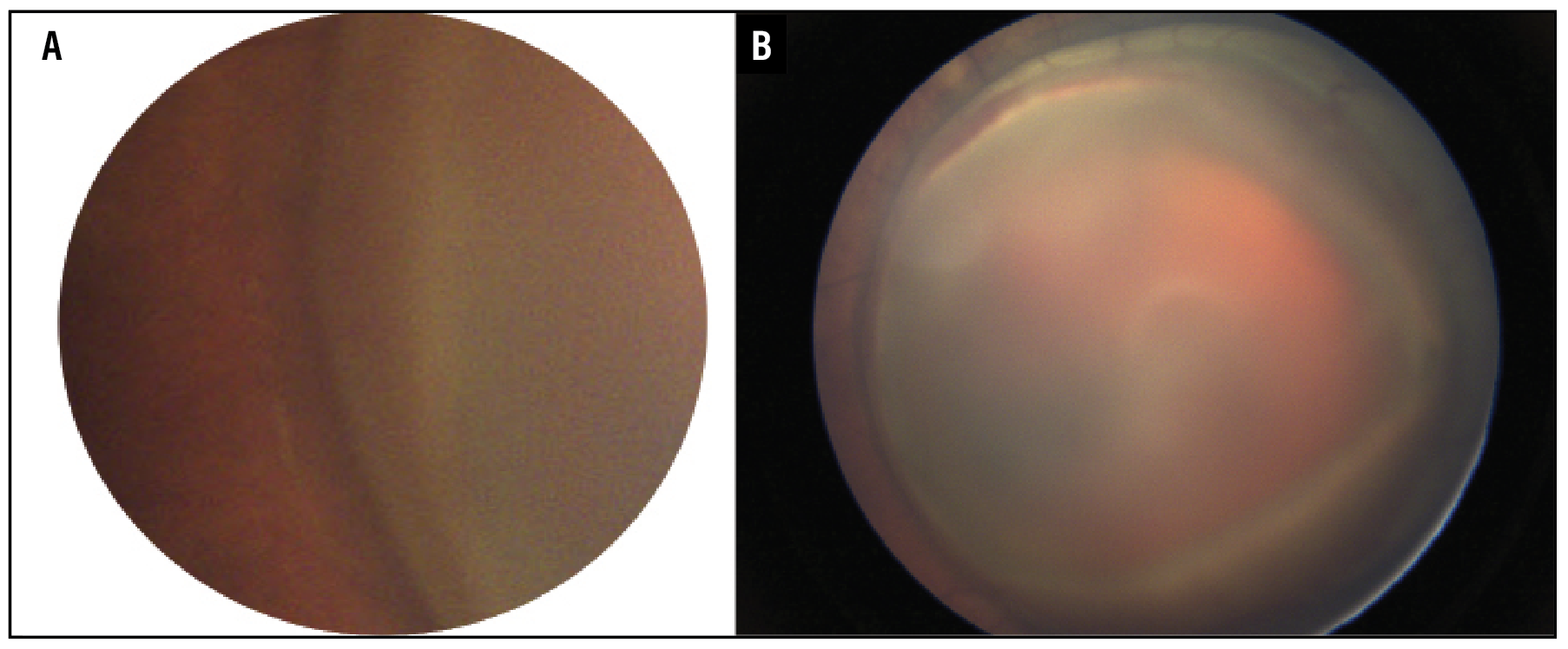

In a 6-month-old with a history of abusive head trauma, examination demonstrated a limited view of the retina (Figure 1A). Subinternal limiting membrane hemorrhage was noted to be encompassing the macula and most of the posterior retina (Figure 1B). Clearing the sub-ILM hemorrhage involved removing the anterior-posterior traction 360 degrees around the hemorrhage as well as in the sub-ILM space without creating a break.

|

|

Figure 1. A) Fundus photo of a 6-month-old baby with a history of abusive head trauma demonstrates a limited view of the retina. B) A subinternal limiting membrane hemorrhage encompasses the macula and most of the posterior retina. |

In another case, Dr. Campbell reported on an ex-26-week premature baby presenting as a near 40-week old baby with retinopathy of prematurity with continued progression after laser treatment. Exam under anesthesia revealed stage 4 retinal detachments (Figure 2A). Fluorescein angiography revealed a fibrovascular membrane with leakage at the disc and arcades (Figure 2B).

In this scenario, Dr. Campbell emphasized not to rush into a hot, active eye. The baby was given bilateral intravitreal bevacizumab. Neovascularization and tractional schisis resolved in the left eye with just intravitreal bevacizumab and panretinal photocoagulation.

The right eye required a lens-sparing vitrectomy (Figure 2C). Selective areas of anterior-posterior traction were gently released without causing iatrogenic breaks with aggressive maneuvers. The enemy of good is better: Don’t aim for perfection, and get out of the eye safely. The patient achieved an excellent anatomic result with a flat retina three years out from surgery (Figure 2D).

|

| Figure 2. Widefield fundus imaging of the right eye in a former 26-week-old premature baby with retinopathy of prematurity. A) The right eye shows stage 4 ROP. B) Fluorescein angiography shows leakage from the disc extending to the arcades. C) Vascular activity has decreased after an intravitreal bevacizumab injection, but the tractional retinal detachment persists as folds. D) The nicely flattened retina after lens-sparing vitrectomy with membrane peeling. |

Amniotic membrane graft for chronic macular holes

By Suzanne Michalak, MD

|

|

Dr. Michalak is a second-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow at Byers Eye Institute, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Michalak serves on an advisory board for AbbVie/Allergan. |

|

Rachel Mogil, MD, a second-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., presented a novel technique developed alongside Raymond Iezzi, MD, for closure of chronic macular holes following previous surgical failure with vitrectomy, ILM peeling and gas.2 The premise is to leave an amniotic membrane patch graft covering the hole under silicone oil for three months.

The technique involves first inserting the standard three 23-gauge trocar ports and then a chandelier system. The next step is to ensure a complete vitrectomy has been performed previously with careful shaving of the vitreous base. The ILM is then stained with ICG, and any prior ILM peel extended to the arcades. Restaining confirms ILM removal.

A corneal trephine is then used to size the amniotic membrane outside the eye. The amniotic membrane is then inserted into the eye through one of the 23-g cannulae using a 25-g forceps. A second forceps is used to unfurl the patch and to identify the chorion (sticky) side, which tends to scroll into itself and stick to the forceps.

|

Using a bimanual technique, the amniotic membrane is placed over the macular hole, chorion side down. Perfluoro-octane is injected onto the patch to stabilize it. Direct PFO/silicone oil exchange is then performed and intraoperative optical coherence tomography helps to confirm positioning and complete amniotic membrane graft coverage of the hole. The cannulae are removed and sclerotomies sutured.

Three months later, the team returns to remove the silicone oil and amniotic membrane. The results from the case presented were quite impressive for a chronic macular hole. Preoperative vision was 20/600 and vision three months following silicone oil/graft removal was 20/40. They plan an upcoming case series detailing more patients in whom this technique has been used successfully for chronic macular holes.

Pearls for retinal surgery in patients with diabetes

By Abtin Shahlaee, MD

|

|

Dr. Shahlaee is a second-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow at Wills Eye Hospital/Mid Atlantic Retina in Philadelphia. DISCLOSURE: Dr. Shahlaee has no relevant disclosures. |

|

Irene Roh, MD, a vitreoretinal surgeon at Joslin Diabetes Center/Beetham Eye Institute in Boston, shared these pearls for optimizing surgical outcomes in patients with diabetic retinopathy.3

Preoperative evaluation. Establish goals for surgery, including an estimation of visual potential as guided by your preoperative examination and, possibly, fluorescein angiography or OCT angiography. For example, evaluating the hyaloid status allows you to determine the optimal location to begin membrane dissection, specifically targeting the area where the separation between the posterior hyaloid and the underlying retinal surface is most pronounced.

Handle the hyaloid. The initial stages of diabetic vitrectomy typically involve addressing anterior-to-posterior traction and detaching and removing the posterior hyaloid. Releasing the hyaloid establishes the appropriate surgical plane, facilitating the removal of fibrovascular membranes.

By utilizing small-gauge instruments and intraocular forceps, the dissection of membranes becomes more precise, enabling improved access to the membranes and potential space. Regardless of the perceived difficulty or inoperability of a tractional retinal detachment (TRD), a disciplined approach can lead to successful outcomes.

|

Improve your view. Clear visualization is of utmost importance, particularly when dealing with complex dissections and lengthy surgical procedures. Patients with diabetes often have friable corneal epithelium, so use the appropriate viscoelastic agents. For phakic patients, incorporating dextrose into the balanced salt solution infusion can minimize lens opacity during the operation. In more advanced cataracts, consider simultaneous cataract extraction to ensure a clear view for vitrectomy.

Control bleeding. Early and consistent hemostasis is crucial. Prolonged and uncontrolled bleeding can obscure the surgical view. The formation of pseudomembranes due to coagulated blood can further complicate membrane dissection. While elevating the intraocular pressure can be helpful, Dr. Roh recommended diathermy or long-duration endolaser to address the underlying cause of bleeding. Prolonged pressure can lead to premature corneal edema, worsening of ischemia and optic neuropathy.

Intravitreal triamcinolone. This can aid in visualizing vitreoschisis and removing the hyaloid.

It’s not just about the surgery. Postoperatively, patients need close monitoring to evaluate for further DR complications, such as recurrent neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage, macular edema, retinal redetachments, proliferative vitreoretinopathy and cataract and epiretinal membrane formation.

US-guided vitrectomy: A solution to the dreaded ‘blind vitrectomy’

By Margaret M. Runner, MD

|

|

Dr. Runner is a second-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow with Associated Retinal Consultants at Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich. DISCLOSURE: Dr. Runner disclosed relationships with Alimera Sciences and AbbVie/Allergan. |

|

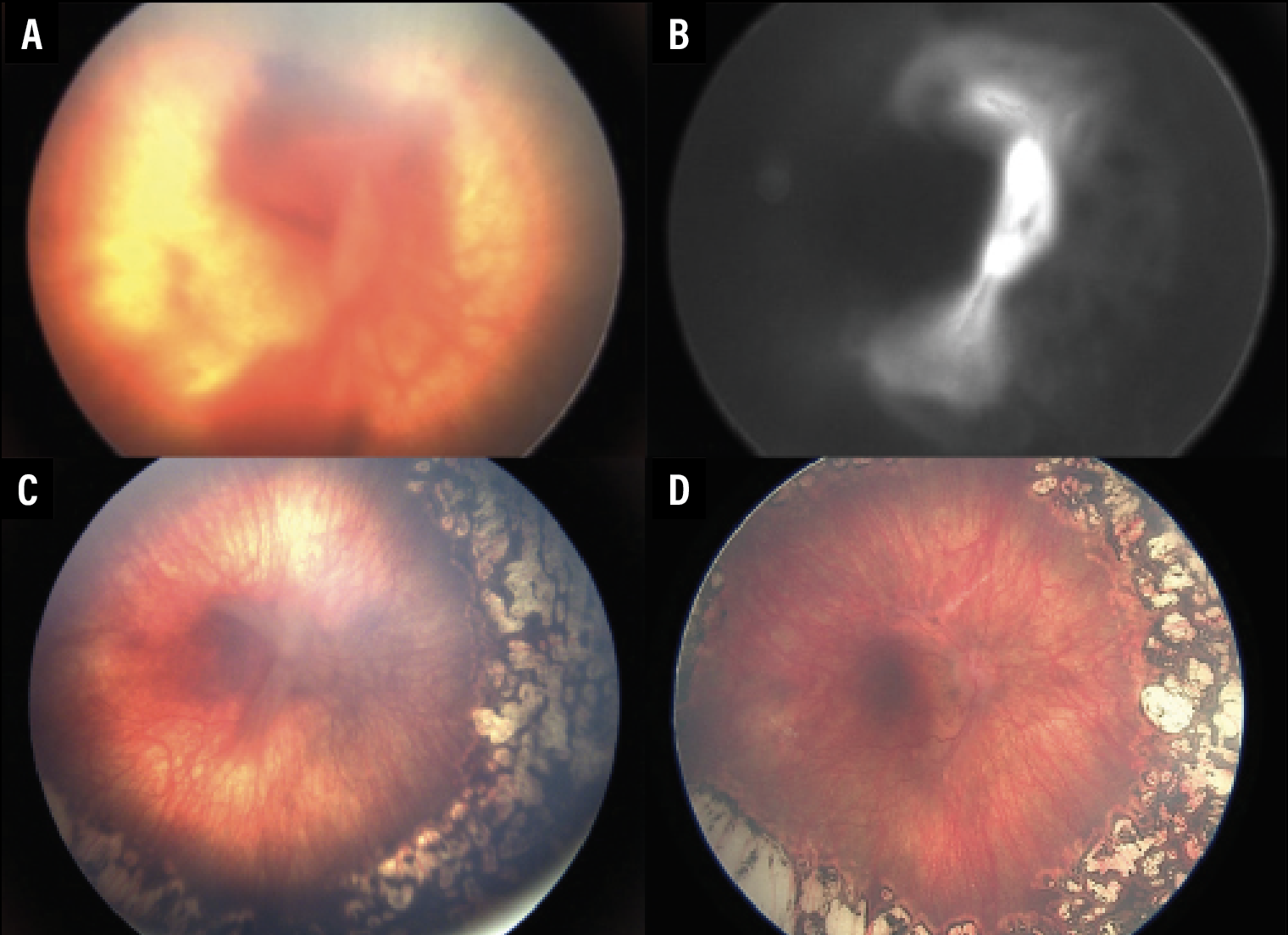

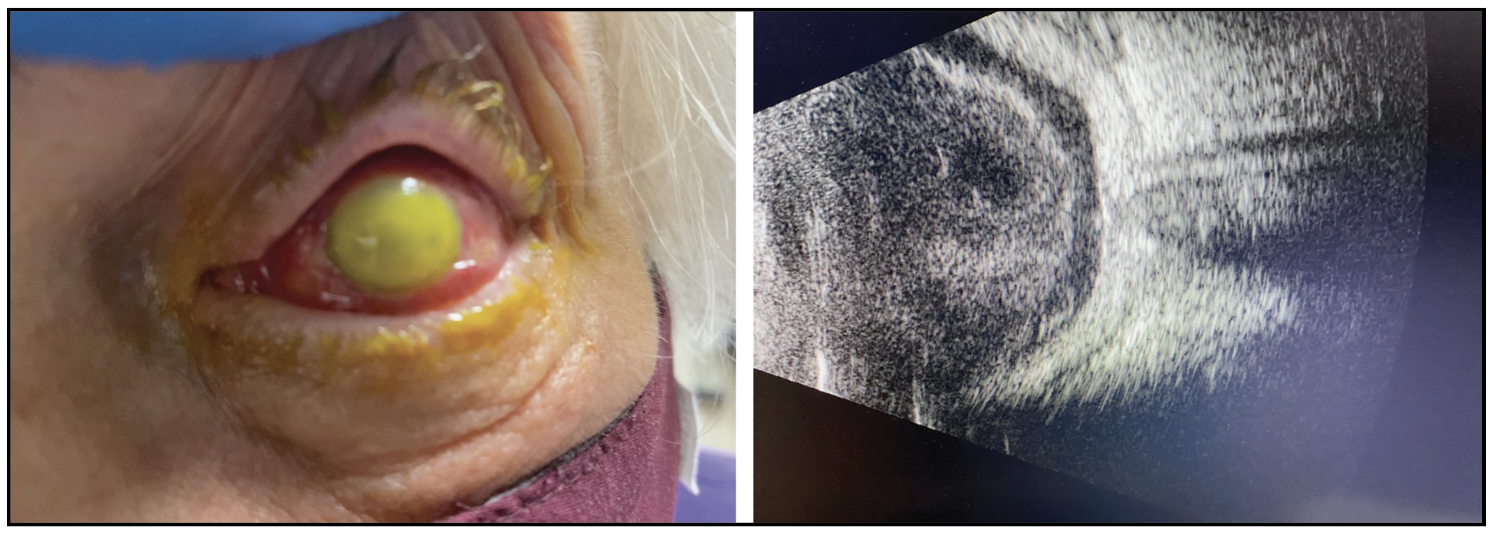

Raul Velez-Montoya, MD, presented a novel technique for using intraoperative B-scan ultrasonography to guide vitrectomy in eyes with infectious keratitis endophthalmitis.4 Patients with advanced endophthalmitis (Figure 3) may present with light perception vision or worse with minimal improvement after intravitreal antibiotics and aggressive topical therapy, thus prompting surgeons to consider vitrectomy.

Despite anterior chamber wash-outs, synechiolysis or corneal scraping, the view to the posterior pole can still be limited. To address this issue, Dr. Velez-Montoya, of the Association to Avoid Blindness in Mexico in Mexico City, demonstrated a technique utilizing intraoperative B-scan ultrasonography to visualize the cutter tip in relation to the eye wall. By holding in one hand the B-scan probe, protected in a sterile sleeve, and in the other the vitreous cutter, the surgeon can visualize the cutter on the monitor as a bright hyperechoic signal with posterior shadowing.

This technique may facilitate limited vitrectomy in challenging cases where there’s no view to the posterior pole, when endoscopes may not be available and/or temporary keratoprostheses (TKP) may be contraindicated. Dr. Velez-Montoya confirmed that standard stainless-steel vitrectomy cannulae don’t cause excessive internal echo noise to interfere with visualization by the probe. He recommended the standard 10-Mhz B-scan probe for visualization of intraocular landmarks.

Once the vitreous cutter’s bright echo is visualized and in a good location, the foot pedal is engaged and the cutter left in place until there’s no further movement of vitreous toward the cutter on the monitor. The procedure is repeated several times in different projections to safely remove the maximum amount of vitreous.

|

| Figure 3. External photograph and B-scan ultrasonography of a 71-year-old male patient who presented two days after intravitreal aflibercept injection with corneal opacification and dense vitritis. Baseline vision was light perception with minimal improvement after intravitreal antibiotics and topical therapy, therefore patient underwent surgery two days after presentation. Vitreous cultures ultimately grew Streptococcus mitis. |

To test this technique, Dr. Velez-Montoya enrolled patients with infectious keratitis endophthalmitis needing a PPV who weren’t candidates for TKP. Baseline visual acuity was 2.3 ± 0.25 logMAR (light perception) and preoperative ultrasound showed attached retina. Case duration was on average 25 minutes and all patients received intravitreal vancomycin/ceftazidime at the end.

|

Eight patients (66 percent) achieved endophthalmitis inactivation, two ultimately required evisceration due to uncontrolled infection, and two developed retinal detachment at post-op weeks six and eight. Visual acuity at three months post-op had improved to 2.1 ± 0.25 logMAR (hand motions) in this small cohort. The adverse events during follow-up were likely related more to the severity of the endophthalmitis rather than the ultrasound-guided vitrectomy. Although further studies are needed, this approach is a feasible alternative to visualize the position of the vitreous cutter rather than using the traditional “blind vitrectomy” for severe active endophthalmitis cases.

Tips for intraocular foreign body removal

By Thomas Lazzarini, MD

|

|

Dr. Lazzarini is a second-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami. DISCLOSURE: Dr. Lazzarini is a consultant to Regenxbio. |

|

Vivek Dave, MD, used several cases to highlight practical surgical tips on the management of intraocular foreign bodies (IOFB) in ruptured globe injuries.5 IOFBs can be contained to the anterior segment or localized to the posterior segment following scleral injury or a corneal injury with lens or zonular violation.

In his first case, Dr. Dave, of the Anant Bajaj Retina Institute, LV Prasad Eye Institute in Hyderabad, India, reported on a patient with a corneal laceration and a retained metallic posterior-segment IOFB. Anterior-chamber and vitreous hemorrhage prevented visualization to the posterior segment. In such cases, a front-to-back approach is prudent to clear media in a stepwise fashion to safely enter the posterior segment and retrieve the foreign body.

First, an anterior chamber wash-out with the placement of an anterior infusion clears the hemorrhage and hyphema. A complete lensectomy via phacoemulsification or phaco-fragmentation follows. The anterior chamber infusion may improve the vitreous hemorrhage in the anterior vitreous.

Once posterior visualization is established, a posterior vitreous detachment is induced prior to IOFB retrieval to minimize vitreous traction and to reduce the risk of subsequent retinal detachment. PFO can prevent iatrogenic macular damage from the IOFB, which may fall posteriorly during removal.

An intraocular magnet is a good tool for removing metallic foreign bodies. Other options include intraocular forceps or aspiration with a cannula. With standard intraocular forceps, such as ILM forceps, the prongs may be spread manually for a larger foreign body. In aphakic patients, the IOFB may be removed via a scleral tunnel or clear corneal wound, or via an enlarged, circumferential pars plana incision regardless of the lens status.

If a retinal detachment is identified, additional PFO may stabilize the retina during IOFB removal. Once the foreign bodies are removed, PFO may be brought up to drain the retina flat via a peripheral break or retinotomy. At this point, a direct PFO/silicone oil exchange or a fluid-air exchange is performed, followed by a gas or silicone oil tamponade, with the latter favored. All breaks should be lasered. A 360-degree peripheral laser can be considered given the possibility of missed or microscopic breaks in the setting of severe trauma.

Dr. Dave’s second case demonstrated a technique for identifying foreign bodies hidden in the anterior chamber angle. The patient had inferior corneal edema and a self-sealing corneal laceration after an accident involving broken glass. A foreign body was suspected but couldn’t be visualized because of the corneal edema.

In the operating room, the anterior chamber was filled with Healon, which also inflated the inferior angle. An endoscope helped visualize the angle, revealing a small piece of glass. Forceps were used to grasp and remove the glass through a limbal corneal wound. The corneal edema subsequently improved. RS

REFERENCES

1. Campbell JP. Pediatric retina surgery tips. Paper presented at Vit Buckle Society; April 14, 2023; Las Vegas, NV.

2. Mogil R, Iezzi R. Paper presented at Vit Buckle Society; April 14, 2023; Las Vegas, NV.

3. Roh I. Pearls for diabetic surgery. Paper presented at Vit Buckle Society; April 14, 2023; Las Vegas, NV.

4. Montoya RV. Session 9: International Surgical Retina “With Great Powre Comes Great Resonsibility.” Paper presented at Vit Buckle Society; April 15, 2023; Las Vegas, NV.

5. Dave V. Intraocular foreign bodies—the extreme ones! Paper presented at Vit Buckle Society; April 14, 2023; Las Vegas, NV.