|

|

Bio Dr. Durrani is a first-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow at Mid Atlantic Retina/Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia. Dr. Hsu is an attending physician at Mid Atlantic Retina and the Retina Service of Wills Eye Hospital. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Durrani and Dr. Hsu have no relevant financial relationships to disclose. |

Examination findings

The patient’s visual acuity was counting fingers in the right eye and 20/25 in the left. Intraocular pressures were within normal limits in both eyes. Anterior segment examination was significant for trace nuclear sclerosis in both eyes. The anterior chamber and anterior vitreous were notably quiet bilaterally.

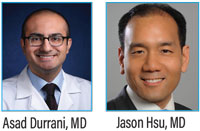

Fundus examination of the right eye (Figure 1A) demonstrated clear vitreous without vitritis. The optic nerve was flat with sharp margins. Circumpapillary and contiguous to the disc, there was a large helicoid area of chorioretinal atrophy with intermixed hyperpigmentation involving the entire macula. The vessels were of normal course and caliber without sheathing and the periphery was unremarkable.

Fundus examination of the left eye (Figure 1B) also demonstrated clear vitreous without vitritis. The optic nerve head was flat with sharp margins. Circumpapillary and contiguous to the disc was a helicoid area of chorioretinal atrophy, smaller than the right eye, with intermixed hyperpigmentation abutting, but not involving, the fovea.

The left eye also showed an area of hypopigmentation along the inferior arcade at the edge of chorioretinal atrophy in the left eye. The vessels were of normal course and caliber without sheathing and the periphery was unremarkable.

|

|

Figure 1. Pseudocolor fundus imaging demonstrates bilateral helicoid chorioretinal atrophy emanating from the disc. |

Imaging results

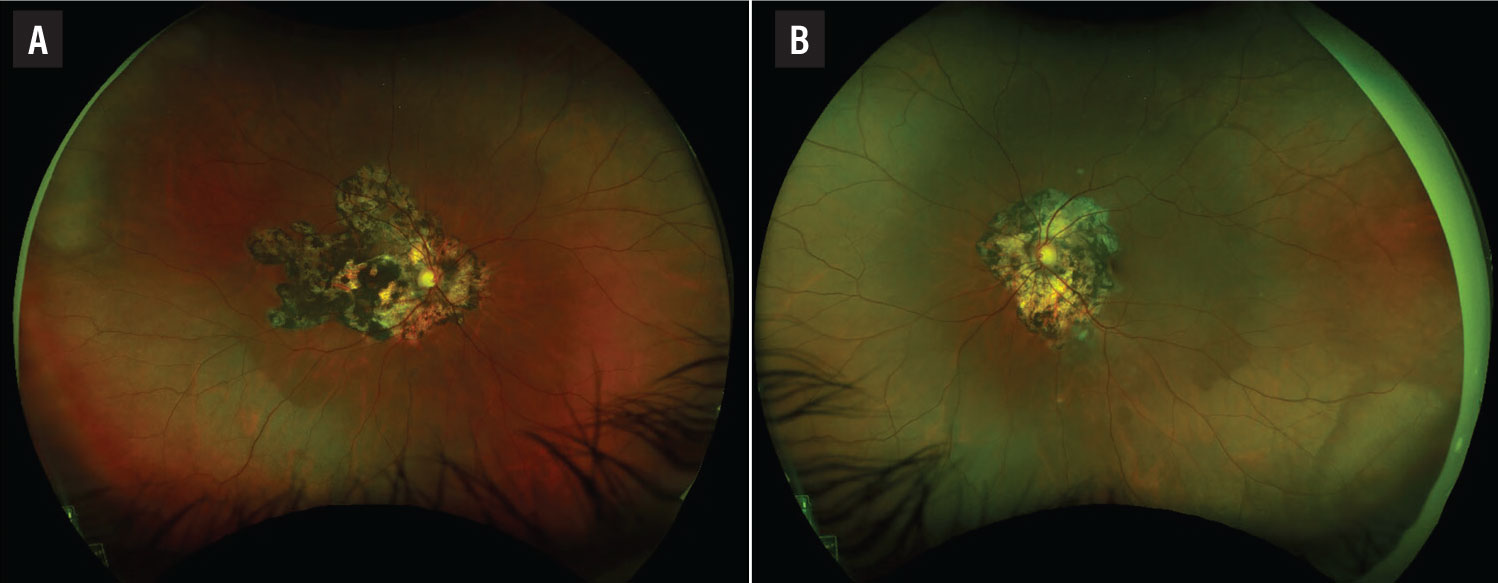

Optical coherence tomography of the macula showed preserved inner retinal laminations with large areas of outer retinal atrophy and retinal pigment epithelium migration the right eye (Figure 2A) and outer retinal atrophy in the nasal macula with preserved inner and outer retinal lamination subfoveally and in the temporal macula in the left eye (Figure 2B).

|

|

Figure 2. A) Optical coherence tomography shows marked outer retinal atrophy involving the entire macula in the right eye. B) The fovea and temporal macula in the left eye are spared. |

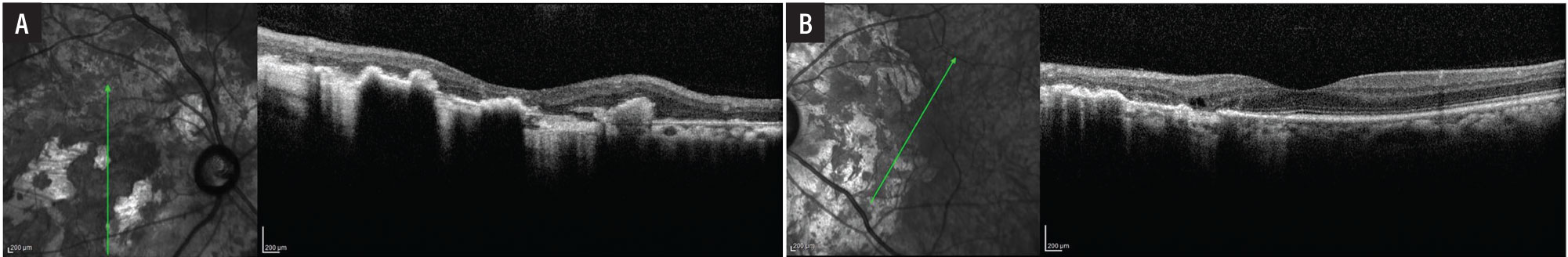

Fundus autofluorescence demonstrated dense hypoautofluorescence in the area of chorioretinal atrophy in the right eye (Figure 3A) and dense hypoautofluorescence in the area of chorioretinal atrophy with an adjacent area of hyperautofluorescence along the inferior arcade in the left eye (Figure 3B).

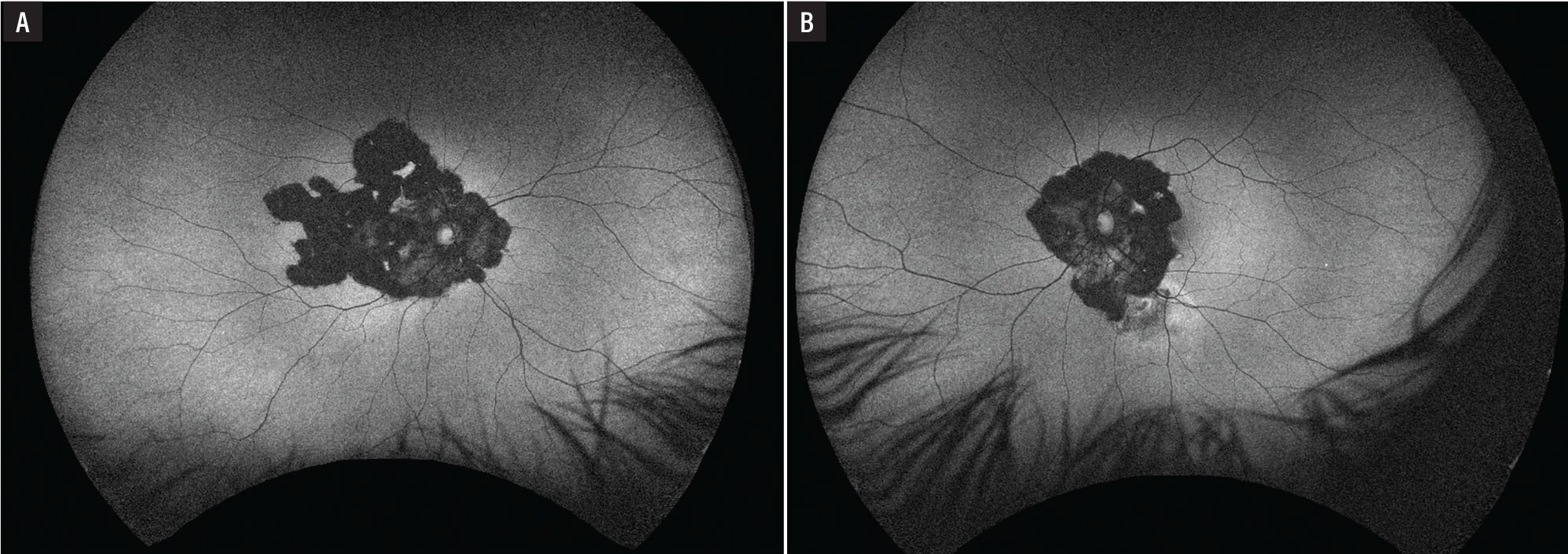

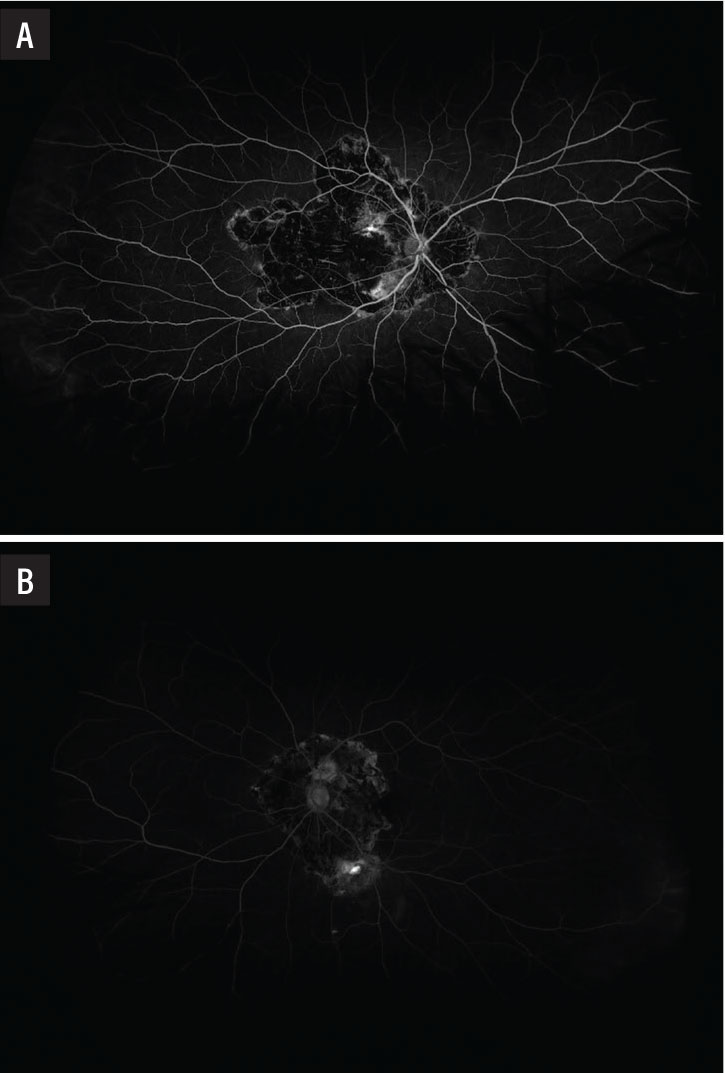

Fluorescein angiogram showed a large window defect in the area of chorioretinal atrophy with interspersed hypofluorescence from blockage due to hyperpigmentation and hyperfluorescence from the choroidal vasculature of the right eye (Figure 4A) and a similar pattern of fluorescence in the area of chorioretinal atrophy with an area of late leakage along the inferior arcade concerning for disease activity in the left eye (Figure 4B).

Additional history and diagnosis

Given the classic appearance, we obtained a limited laboratory work-up. A negative QuantiFERON Gold test ruled out serpiginous-like choroiditis. We diagnosed serpiginous choroiditis with an acute flare in the left eye. Another provider had already prescribed maintenance therapy with adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) and mycophenolate, so we started high-dose oral steroids to manage his acute flare.

|

|

Figure 3. Fundus autofluorescence reveals dense hypofluorescence in both eyes with a leading edge of hyperfluorescence in the left eye (B) concerning for activity. |

Serpiginous choroiditis

Serpiginous choroiditis is a bilateral chronic inflammatory disease of the RPE and choriocapillaris that often recurs despite appropriate treatment. This is a rare cause of posterior uveitis, estimated to cause less than 5 percent of all posterior uveitides.1 The disease typically effects middle-aged adults without any gender predilection.2

The etiology of serpiginous choroiditis remains unknown. Proposed etiologies include an association with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B7, given the increased frequency of this HLA type in patients with serpiginous choroiditis, herpetic disease or an immune response to retinal S-antigen, a protein found in the membrane of the photoreceptor outer segments.3

Serpiginous choroiditis is often asymmetrical. Patients typically present with vision loss in one eye. The lesions in this disease start in the peripapillary region and spread in a helicoid or snake-like manner into the macula and mid-periphery. These lesions have a leading edge that, once resolved, leave chorioretinal atrophy with interspersed hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation on funduscopic examination.

Vitreous inflammation is minimal or absent. Fundus autofluorescence and fluorescein angiography are helpful ancillary imaging modalities to assess disease activity at the atrophy margins.4 OCT can help monitor for juxtafoveal or foveal involvement, which leads to rapid loss of visual acuity.

|

|

Figure 4. A) Fluorescein angiogram in the right eye showed a window defect with inactive choroiditis. B) The left eye demonstrated a window defect with an area of active leakage along the inferior arcade. |

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes serpiginous-like choroiditis, persistent placoid maculopathy, ampiginous choroiditis and acute multifocal posterior placoid pigment epitheliopathy.

It’s crucial to differentiate serpiginous choroiditis from serpiginous-like choroiditis secondary to tuberculosis.5 Serpiginous-like choroiditis tends to present with multifocal or placoid lesions in the posterior pole with vitritis and anterior chamber reaction.6 Often, the lesions in serpiginous-like choroiditis aren’t contiguous with the disc as in serpiginous choroiditis. Patients with serpiginous-like choroiditis secondary to tuberculosis require antituberculosis drug therapy. A QuantiFERON Gold test is mandatory before initiating steroid or immunosuppression therapy in cases of serpiginous choroiditis.

Treatment and long-term prognosis

The natural history of serpiginous choroiditis includes multiple recurrences with eventual foveal involvement. The mainstay of treatment involves immunosuppressive therapy with steroid-sparing agents to prevent vision loss.

No agreed-upon best treatment exists for this challenging disease. Multiple regimens have been proposed, including systemic steroids alone or systemic steroids combined with agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil or anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents.7-8 These agents have various side effects, ranging from mild to severe or life-threatening. For this reason, consultation with a rheumatologist is often recommended when treating this condition.

Systemic corticosteroids, periocular steroids and/or intravitreal steroids may be necessary to rapidly control the disease when it recurs or threatens the fovea. Despite aggressive immunosuppression, many patients will experience a decline in visual acuity due to eventual foveal involvement. A small number of patients also may experience vision loss due to secondary choroidal neovascular membrane formation.9

Bottom line

Serpiginous choroiditis is a rare cause of posterior uveitis characterized by bilateral inflammation of the retinal pigment epithelium and choriocapillaris that frequently recurs despite aggressive immunosuppression. The helicoid chorioretinal atrophy emanating from the optic nerve is characteristic of this disease. Fundus autofluorescence is an excellent imaging modality to monitor for recurrence. Rule out serpiginous-like choroiditis secondary to tuberculosis infection because the management of this related entity is antibiotic therapy. RS

REFERENCES

1. Chang JH, Wakefield D. Uveitis: A global perspective. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2002;10:263-279.

2. Sen HN, Davis J, Ucar D, Fox A, Chan CC, Goldstein DA. Gender disparities in ocular inflammatory disorders. Curr Eye Res. 2015;40:146-161.

3. Broekhuyse RM, Van Herck M, Pinckers AJ, et al. Immune responsiveness to retinal S-antigen and opsin in serpiginous choroiditis and other retinal diseases. Doc Ophthalmol. 1988;69:83-93.

4. Cardillo Piccolino F, Grosso A, Savini E. Fundus autofluorescence in serpiginous choroiditis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:179-185.

5. Majumder PD, Biswas J, Gupta A. Enigma of serpiginous choroiditis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:325-333.

6. Khanamiri HN, Rao NA. Serpiginous choroiditis and infectious multifocal serpiginoid choroiditis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58:203-232.

7. Lim WK, Buggage RR, Nussenblatt RB. Serpiginous choroiditis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50:231-244.

8. Akpek EK, Jabs DA, Tessler HH, Joondeph BC, Foster CS. Successful treatment of serpiginous choroiditis with alkylating agents. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1506-1513.

9. Christmas NJ, Oh KT, Oh DM, Folk JC. Long-term follow-up of patients with serpiginous choroiditis. Retina. 2002;22:550-556.