|

|

Pars plana vitrectomy was first reported as a potential therapeutic tool for patients with uveitis in 1981, demonstrating an improvement in visual acuity in 75 percent of eyes in a series of 28 patients.1 In the decades since, techniques and technologies have evolved, and PPV has further emerged as an important therapeutic and diagnostic tool in uveitic patients.

As a therapeutic approach, reported benefits of PPV for uveitis include the removal of inflammatory cells and cytokines, the debulking of vitreous opacities and membranes, the repair of associated retinal pathology and the potential to reduce cystoid macular edema.2,3 Several studies have suggested that PPV may also be helpful in reducing the burden of systemic therapy in select patients with uveitis.3 Here, we outline current applications of PPV in the diagnosis and treatment of uveitis.

Diagnostic PPV for undifferentiated uveitis

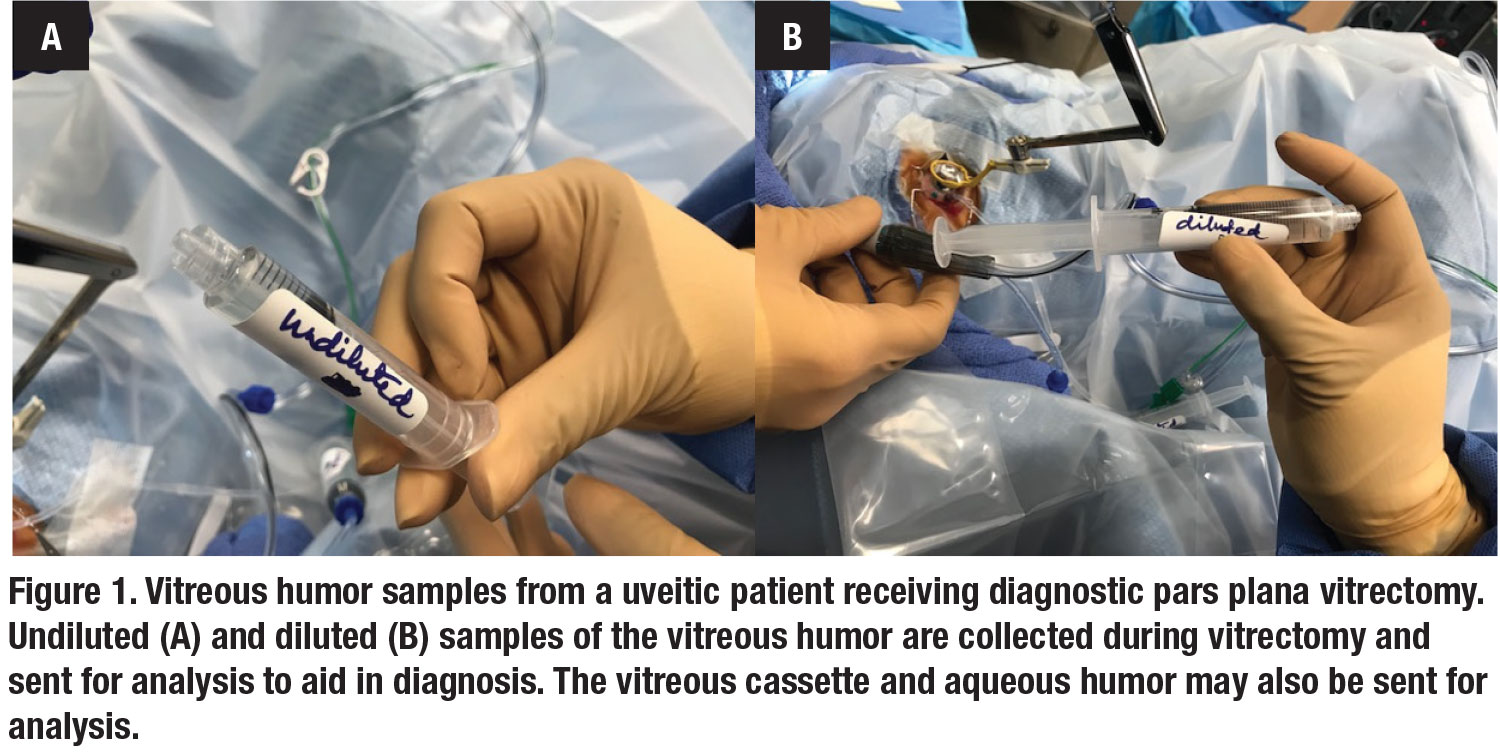

In cases of undifferentiated uveitis, PPV can serve as a valuable diagnostic tool to identify infection, detect malignancy and explore potential alternative diagnoses. Biopsy samples obtained during PPV to assess for underlying pathology typically include undiluted vitreous, diluted vitreous and the vitreous cassette samples (Figure 1). Working with a dedicated ocular pathologist is particularly helpful to differentiate the infectious, autoimmune or malignant ophthalmic processes.

In cases of suspected infection, standard stains and cultures are performed for bacteria, fungus and mycobacterium. Additionally, multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test may be ordered to detect herpes simplex virus 1 or 2, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and toxoplasmosis, among others.

If needed, bacterial, fungal and acid-fast bacilli DNA sequencing can be obtained through labs such as at the University of Washington. In cases of suspected malignancy, molecular genetics, immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry may be indicated.

Cytology may also be beneficial in cases of autoimmune uveitis to distinguish granulomatous vs. non-granulomatous inflammation, an important distinction for determining the etiology of ocular inflammation.

In four recent studies evaluating PPV in uveitis, a definitive diagnosis was established in 20 to 60 percent of cases. Aggregating the results of these studies, vitreous biopsies provided the diagnosis in 34 percent (85/248) of undifferentiated eyes, returning positive for such conditions as endogenous mycosis (31 eyes), lymphoma (21 eyes), toxoplasma chorioretinitis (10 eyes), HZV and/or acute retinal necrosis (10 eyes), benign neoplastic masquerades (six eyes) and other miscellaneous infections (seven eyes).3–7

Therapeutic PPV in uveitis

PPV also serves a therapeutic role for certain uveitic patients. Although indications for therapeutic PPV in the setting of uveitis are broad and varied, studies have reported meaningful improvements in anatomic and visual outcomes, along with the potential for reduction in the need for systemic treatment.

|

A systematic review of PPV for uveitis from 2005 to 2014 reported improved CME, enhanced visual acuity and reduced need for corticosteroids and immunomodulatory therapy following PPV.3 In this review, 69 percent of uveitic eyes demonstrated improved VA compared to 13 percent with worsening VA following PPV. Additionally, 14 of 16 studies demonstrated a reduction in the percentage of patients with CME. Meanwhile, median use of systemic corticosteroids decreased from 48 percent preoperatively to 12 percent postoperatively and median use of systemic immunomodulatory drugs decreased from 56 percent preoperatively to 36 percent postoperatively.

Additional studies have examined the efficacy of PPV in infectious uveitis. In a study from India of patients with bilateral posterior uveitis due to ocular tuberculosis, eyes undergoing PPV had improved control of ocular inflammation at postoperative months one and three (74 percent and 97 percent) compared to non-PPV eyes (20 percent and 83 percent), in addition to more significant improvement in best-corrected VA.9

Vitrectomy has also been reported to improve visual outcomes when performed for persistent vitreous inflammation in cases of recalcitrant ocular toxocariasis.10 Similarly, a few recent manuscripts reported PPV to be an effective option to improve vision for both visually significant ocular toxocariasis- and toxoplasmosis-related epiretinal membranes and macular holes.10-12

Vitrectomy is a therapeutic option for certain cases of acute retinal necrosis (ARN), though results are more varied considering the aggressive nature of this condition and its generally poorer prognosis. Studies investigating the role of early PPV in patients with ARN have suggested it may lower rates of ARN-associated rhegmatogenous retinal detachments, but a definitive role in prevention is still unclear.13,14

|

Clinical case study

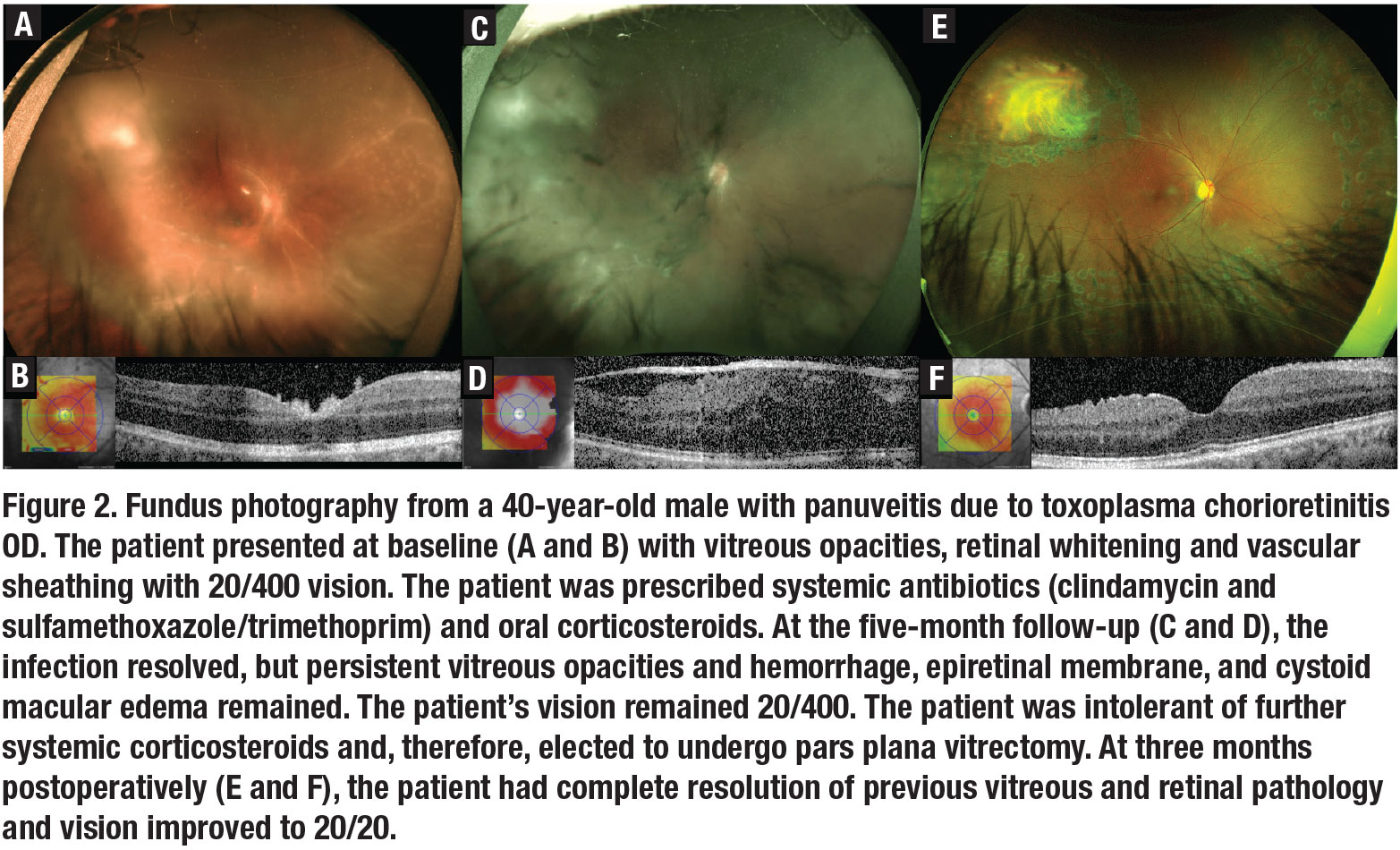

An otherwise healthy 40-year-old man presented to the clinic with panuveitis in the right eye of several months duration and BCVA of 20/400. Imaging showed evidence of severe vitreous debris, an active superotemporal chorioretinal lesion, and profound vascular sheathing (Figure 2A, page 15). The suspected etiology was toxoplasma chorioretinitis, confirmed by anterior chamber PCR and positive serologies. We prescribed an extended course of oral clindamycin and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, in conjunction with a tapered course of prednisone.

At the five-month follow-up visit, the infection had regressed and the chorioretinal lesion was consolidated and inactive. However, the patient had persistent vitreous opacities and hemorrhage in addition to a prominent epiretinal membrane (Figure 2C). The patient also could not tolerate the side effects of a prolonged course of systemic corticosteroids.

Due to the persistent vitreous debris and inability to continue steroids, the patient accepted the option of PPV with membrane peeling. In the meantime, he was continued on maintenance sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim every Monday, Wednesday and Friday to prevent reactivation of infection.

At three months post-PPV, the patient had complete resolution of vitreous debris, haze, retinal edema, and epiretinal membrane with improvement of VA to 20/20 (Figure 2E). At six months post-PPV, the patient had stable vision without recurrence of chorioretinitis, vitritis or epiretinal membrane.

Bottom line

PPV can play an important role in the management of uveitis as both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool. Patient selection is critical, but in appropriate patients, don’t overlook the use of PPV in the management of uveitis. RS

REFERENCES

1. Algvere P, Alanko H, Dickhoff K, Lähde Y, Saari KM. Pars plana vitrectomy in the management of intraocular inflammation. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1981;59:727-736.

2. Becker M, Davis J. Vitrectomy in the treatment of uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:1096-1105.

3. Henry CR, Becker MD, Yang Y, Davis JL. Pars plana vitrectomy for the treatment of uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;190:142-149.

4. Oahalou A, Schellekens PAWJF, de Groot-Mijnes JD, Rothova A. Diagnostic pars plana vitrectomy and aqueous analyses in patients with uveitis of unknown cause. Retina. 2014;34:108-114.

5. Pion B, Valyi ZS, Janssens X, et al. Vitrectomy in uveitis patients. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2013;322:55-61.

6. Svozilkova P, Heissigerova J, Brichova M, Kalvodova B, Dvorak J, Rihova E. The role of pars plana vitrectomy in the diagnosis and treatment of uveitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21:89-97.

7. Margolis R, Brasil OFM, Lowder CY, et al. Vitrectomy for the diagnosis and management of uveitis of unknown cause. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1893-1897.

8. Tranos P, Scott R, Zambarakji H, et al. The effect of pars plana vitrectomy on cystoid macular oedema associated with chronic uveitis: a randomised, controlled pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1107-1110.

9. Kaza H, Modi R, Rana R, et al. Effect of pars plana vitrectomy on focal posterior segment inflammation: a case-control study in tuberculosis-associated uveitis. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018; 2:1163-1169.

10. Despreaux R, Fardeau C, Touhami S, et al. Ocular toxocariasis: clinical features and long-term visual outcomes in adult patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016; 166:162–168.

11. Miranda AF, Costa de Andrade G, Novais EA, et al. Outcomes after pars plana vitrectomy for epiretinal membranes associated with toxoplasmosis. Retina. 2016;36:1713–1717.

12. Sousa DC, Costa de Andrade G, Nascimento H, Maia A, Muccioli C. Macular hole associated with toxoplasmosis.” Retin Cases Brief Rep. Published online June 28, 2018. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000757

13. Huang JM, Callanan P, Callanan D, Wang RC.. Rate of retinal detachment after early prophylactic vitrectomy for acute retinal necrosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;26: 204–207.

14. Risseeuw S, de Boer JH, Ten Dam-van Loon NH, van Leeuwen R. Risk of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in acute retinal necrosis with and without prophylactic intervention. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;206:140–148.