|

A 42-year-old Caucasian male presented with a one-week history of blurry vision, foreign body sensation, eye injection and mild ocular pain in his left eye. His medical history was unremarkable. He wasn’t taking any medications and denied any additional symptoms on a review of systems.

Workup and imaging findings

The patient appeared generally healthy, and his vital signs were within normal limits. On ocular examination, Snellen visual acuity with correction was 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS. Intraocular pressures were 17 mmHg OU. Pupil examination revealed a relative afferent pupillary defect OS. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable OD, but notable OS for moderate conjunctival injection, 2+ anterior chamber cell without keratic precipitates or iris transillumination deficits.

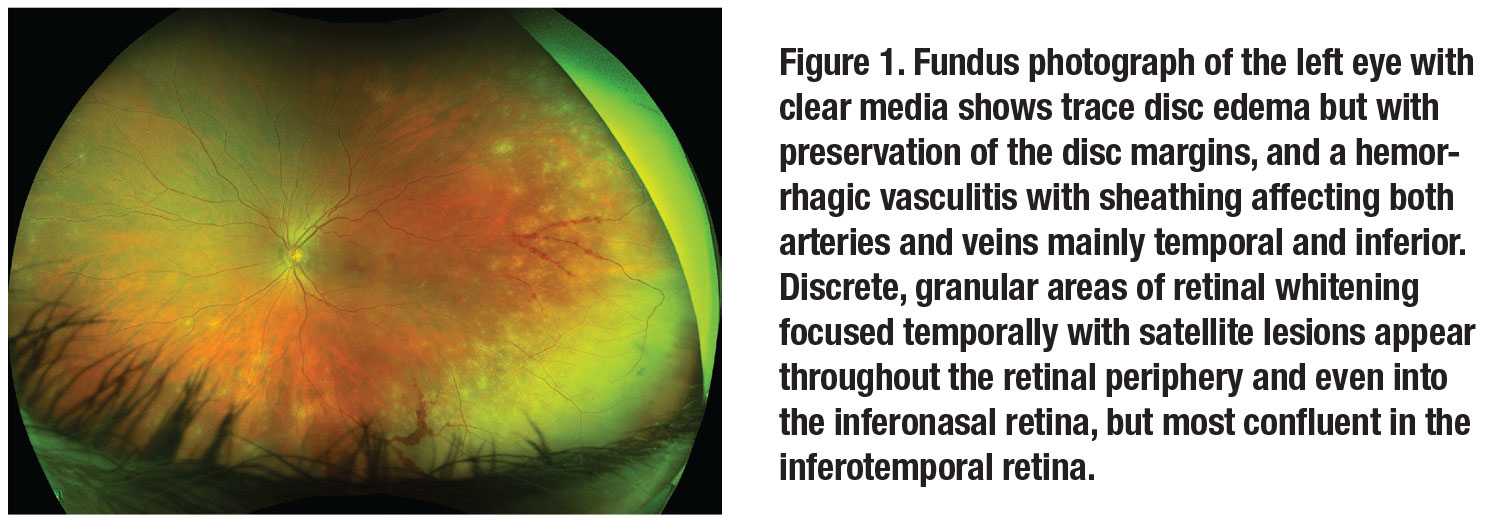

Posterior segment examination of the right eye was unremarkable. Posterior evaluation of the left eye showed 2+ vitreous cell with a large area of retinal whitening in the temporal peripheral retina with scattered patches of retinal whitening extending toward the posterior pole.

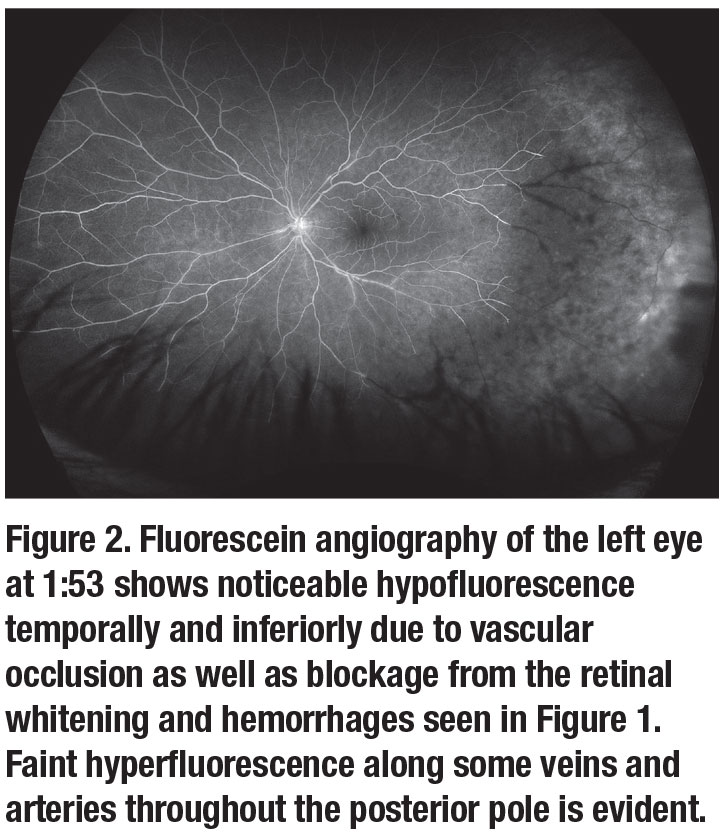

Perivascular hemorrhages with vascular sheathing were visible in the temporal retina (Figure 1). Fluorescein angiography of the left eye (Figure 2) revealed extensive hypofluorescence of the temporal retina likely associated with blocking from the areas of retinal whitening seen on the fundoscopic exam. There were additional areas of hypofluorescence associated with arteriovascular occlusion as well as areas of perivascular hyperfluorescence consistent with leakage.

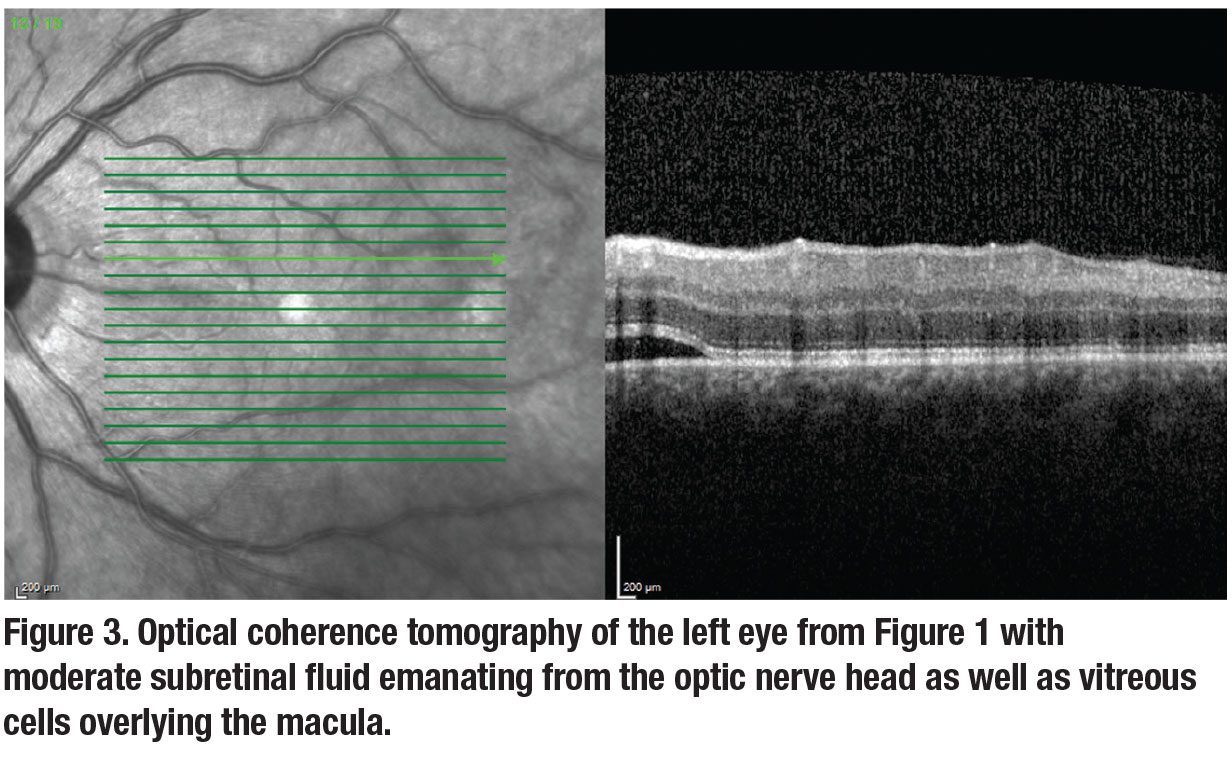

Optical coherence tomography of the left eye revealed subretinal fluid emanating from the optic nerve as well as vitreous cells overlying the macula (Figure 3). The differential diagnosis of this patient with unilateral acute anterior chamber and vitreous inflammation with retinal whitening included infectious and potentially inflammatory etiologies. Infectious causes included bacterial (e.g., tuberculosis, syphilis, Lyme disease), viral (e.g., herpetic necrotizing retinitis, cytomegalovirus retinitis), or parasitic (toxoplasmosis). Inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis, lupus and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis were considered but thought to be less likely.

Early diagnosis is critical

Multimodal imaging played a valuable role in making the diagnosis of acute retinal necrosis (ARN) in this healthy middle-aged male. Early diagnosis of ARN is paramount because any delay in therapy can result in permanent vision loss.

Workup, diagnosis and treatment

Given the significant retinal whitening and evidence of obliterative vasculopathy on fluorescein angiography in the left eye, we emergently treated the patient with a single intravitreal injection of foscarnet 2.4 mg/0.1 mL and initiated oral valacyclovir 2 g t.i.d. We treated the patient’s anterior uveitis with prednisolone acetate 1% q2h and atropine b.i.d. in the left eye.

|

We performed an anterior chamber paracentesis at the time of the intravitreal injection and sent the sample for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for varicella zoster virus (VZV), herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 and -2, cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis.

Blood work including syphilis serologies, quantiFERON-tuberculosis gold, anti-double-stranded-DNA antibody, lupus anticoagulant, angiotensin converting enzyme, a complete blood count, and a complete metabolic panel was normal.

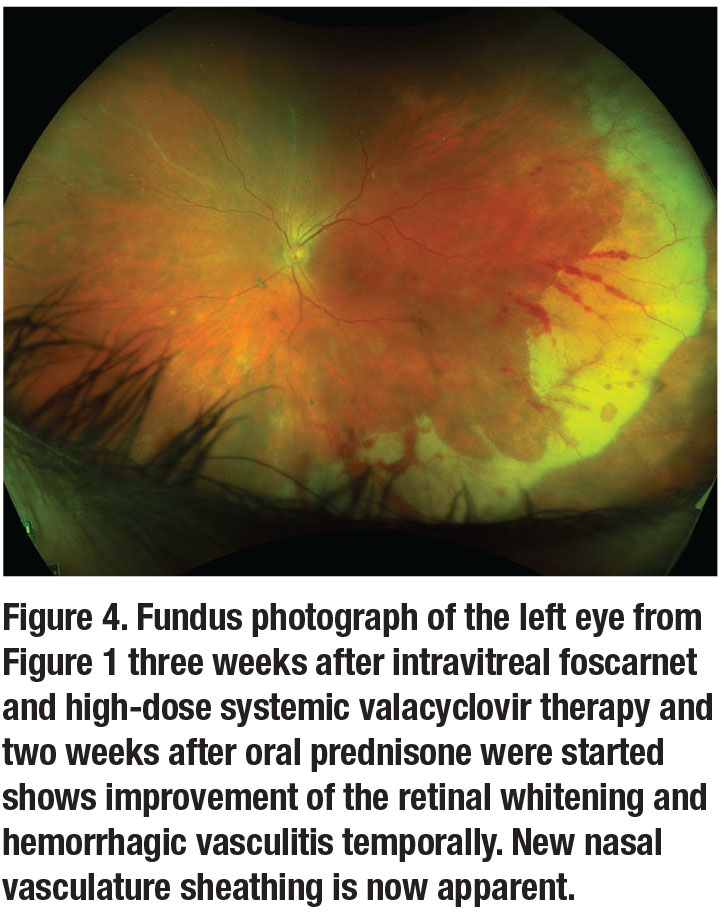

Two days after presentation, the anterior chamber PCR returned positive for VZV. Two days after that we started the patient on oral prednisone 40 mg per day and slowly tapered over three weeks. We also slowly tapered his topical drops as the clinical course improved. Two months after presentation his visual acuity was 20/20 with early atrophy and scarring forming in the periphery. The retina remained attached without the use of prophylactic laser barricade (Figure 4, page 10).

Disease presentation

Acute retinal necrosis typically presents with patches of peripheral retinal whitening that coalesce to form confluent areas of necrotic retina. The spread of the whitening typically occurs centripetally before spreading posteriorly towards the macula.1 New areas of retinal whitening spread rapidly in the absence of antiviral medication, and an obliterative vasculopathy with retinal hemorrhages in the areas of retinal whitening can also occur. Interestingly, the disease routinely spares the macula.

|

The most common isolated viridin is VZV, found in up to two-thirds of patients with ARN,2 while herpes simplex types 1 and 2 are the other common causes. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been a reported cause of ARN; however, definitive proof is scant and most cases believed to be related to EBV were likely due to varicella.2 The retinitis lasts four to six weeks, leaving scarred pigmented lesions in the place of previous retinal whitening.3

The border between the necrotic and perfused retina is a frequent site for the development of retinal tears, with up to 75 percent of untreated eyes developing rhegmatogenous retinal detachments within one to two months after the onset of disease.3 Bilateral involvement has been noted in roughly one-third of untreated cases and usually occurs within six weeks. However, very late involvement, even years after the initial diagnosis, has been reported.4

Making the diagnosis

A high degree of suspicion for ARN is critical when encountering retinal whitening with vitreous inflammation on exam. The diagnosis of ARN is purely clinical. The American Uveitis Society lists the following required criteria when diagnosing ARN:1

- a focus of retinal necrosis with discrete borders;

- rapid progression of the disease in the absence of anti-viral therapy;

- circumferential spread of the disease;

- an occlusive vasculopathy with involvement of the arteries; and

- a significant anterior chamber and vitreous inflammatory response.

The most sensitive and specific means for diagnosis are PCR assays, which are able to detect a single virion from the biopsy.5 Reports have indicated a sensitivity of 100 percent and specificity of 97 percent from vitreous biopsy PCR analyses,6 while anterior chamber analysis can identify the specific viridin in approximately 86 percent of cases.7

|

If clinical suspicion remains high even after negative PCR testing, an endoretinal biopsy may be undertaken, making a note to take a sample in the zone between the normal and necrotic retina as this greatly increases the diagnostic yield.8 Lastly, assessing immune status is crucial; a recent report found that as many as 16 percent of patients presenting with ARN have some form of impaired cellular immunity.9

Bottom line

|

The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s position paper on the management of ARN stated that no differences were found between oral or intravenous antiviral therapies from treatment initiation to initial and complete remission of the necrosis.10 High-dose oral valacyclovir (2 g q.i.d.) can achieve plasma levels similar to that of intravenous acyclovir; however, patients can still achieve favorable outcomes with a dosing of 2 g t.i.d. It’s thus reasonable to treat viral necrosis with initial oral antivirals at the time of presentation.

Additionally, intravitreal antiviral injections such as foscarnet 2.4 mg/0.1 mL or ganciclovir 2 mg/0.1 mL are available as adjunctive therapy to systemic treatment and may further aid in controlling the spread of necrosis.11 No consensus exists on the number of required injections or when to re-dose, but clinicians agree that more aggressive posterior disease may require repeated intravitreal injections.10 Intravitreal injections offer an opportunity for vitreous or anterior chamber sampling, which can aid in identifying the causative virus.

Lastly, the use of prophylactic laser barricade in preventing retinal detachment is highly debatable. No prospective clinical trials have proven the effectiveness of laser demarcation, while the studies advocating for it likely had a component of sampling bias as many of the eyes that didn’t receive laser were more likely to have media opacities limiting its use.12 RS

REFERENCES

|

1. Holland GN. Standard diagnostic criteria for the acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Executive Committee of the American Uveitis Society. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117:663-667.

2. Lau CH, Missotten T, Salzmann J, Lightman SL. Acute retinal necrosis features, management, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:756-762.

3. Duker JS, Nielsen JC, Eagle RC, Bosley TM, Granadier R, Benson WE. Rapidly progressive acute retinal necrosis secondary to herpes simplex virus, type 1. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1638-1643.

4. Fox GM, Blumenkranz M. Giant retinal pigment epithelial tears in acute retinal necrosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:302-306.

5. Short GA, Margolis TP, Kuppermann BD, Irvine AR, Martin DF, Chandler D. A polymerase chain reaction-based assay for diagnosing varicella-zoster virus retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:157-164.

6. Cunningham ET, Short GA, Irvine AR, Duker JS, Margolis TP. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome--associated herpes simplex virus retinitis. Clinical description and use of a polymerase chain reaction--based assay as a diagnostic tool. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:834-840.

7. Tran THC, Rozenberg F, Cassoux N, Rao NA, LeHoang P, Bodaghi B. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of aqueous humour samples in necrotising retinitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:79-83.

8. Pepose JS, Flowers B, Stewart JA, et al. Herpesvirus antibody levels in the etiologic diagnosis of the acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113:248-256.

9. Rochat C, Herbort CP. Acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Lausanne cases, review of the literature and new physiopathogenetic hypothesis. [in German] Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1994;204:440-449.

10. Schoenberger SD, Kim SJ, Thorne JE, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute retinal necrosis: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:382-392.

11. Chau Tran TH, Cassoux N, Bodaghi B, Lehoang P. Successful treatment with combination of systemic antiviral drugs and intravitreal ganciclovir injections in the management of severe necrotizing herpetic retinitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2003;11:141-144.

12. Tibbetts MD, Shah CP, Young LH, Duker JS, Maguire JI, Morley MG. Treatment of acute retinal necrosis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:818-824.