A 77-year-old male was referred to the ocular oncology service at the University of Washington Eye Institute by his primary care physician for evaluation of a choroidal lesion in his left eye found incidentally on imaging. An MRI brain scan, ordered for unrelated dysphagia, showed an ovoid hyperintense lesion in his left globe.

Examination and findings

|

The patient was last seen six years earlier by an ophthalmologist, who noted a choroidal nevus in the superonasal periphery of the left eye. The patient’s ocular history was notable for pseduophakia in both eyes, and his medical history was significant for hypertension and type 2 diabetes.

Upon evaluation at our clinic, visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes. Intraocular pressures were normal, and pupils equal, round and reactive with no relative afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motility was full, as were confrontational visual fields in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination was within normal limits with a posterior chamber intraocular lens in each eye.

The dilated fundus exam in the left eye was notable for a pigmented choroidal lesion in the superonasal periphery with central lipofuscin and associated subretinal fluid. On B-scan ultrasound, the lesion appeared as a dome-shaped mass with medium internal reflectivity, measuring 9 x 7.5 mm with a thickness of 3.4 mm.

Work-up and surgery

Lesion growth, lipofuscin and subretinal fluid were consistent with a diagnosis of choroidal melanoma due to malignant transformation of a choroidal nevus. CT-scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis didn’t show any evidence of visceral metastases or lymphadenopathy. The patient underwent an operation to have tantalum clips placed and had proton beam radiotherapy. During the surgery, a trans-vitreous choroidal fine-needle aspiration was obtained. Castle gene expression profile showed that the lesion was Class 1A, portending a 98 percent chance of metastasis-free survival at five years.

Six months after completing proton beam therapy, the patient returned with vision decreased to light perception in the left eye. Examination revealed no view to the posterior pole, and a dense vitreous hemorrhage precluded ophthalmoscopic examination of the melanoma, which was stable on B-scan. The vitreous hemorrhage was presumed to be due to radiation retinopathy and the patient was referred to the retina service for consideration of pars plana vitrectomy and pan-retinal photocoagulation.

|

A second elevated mass

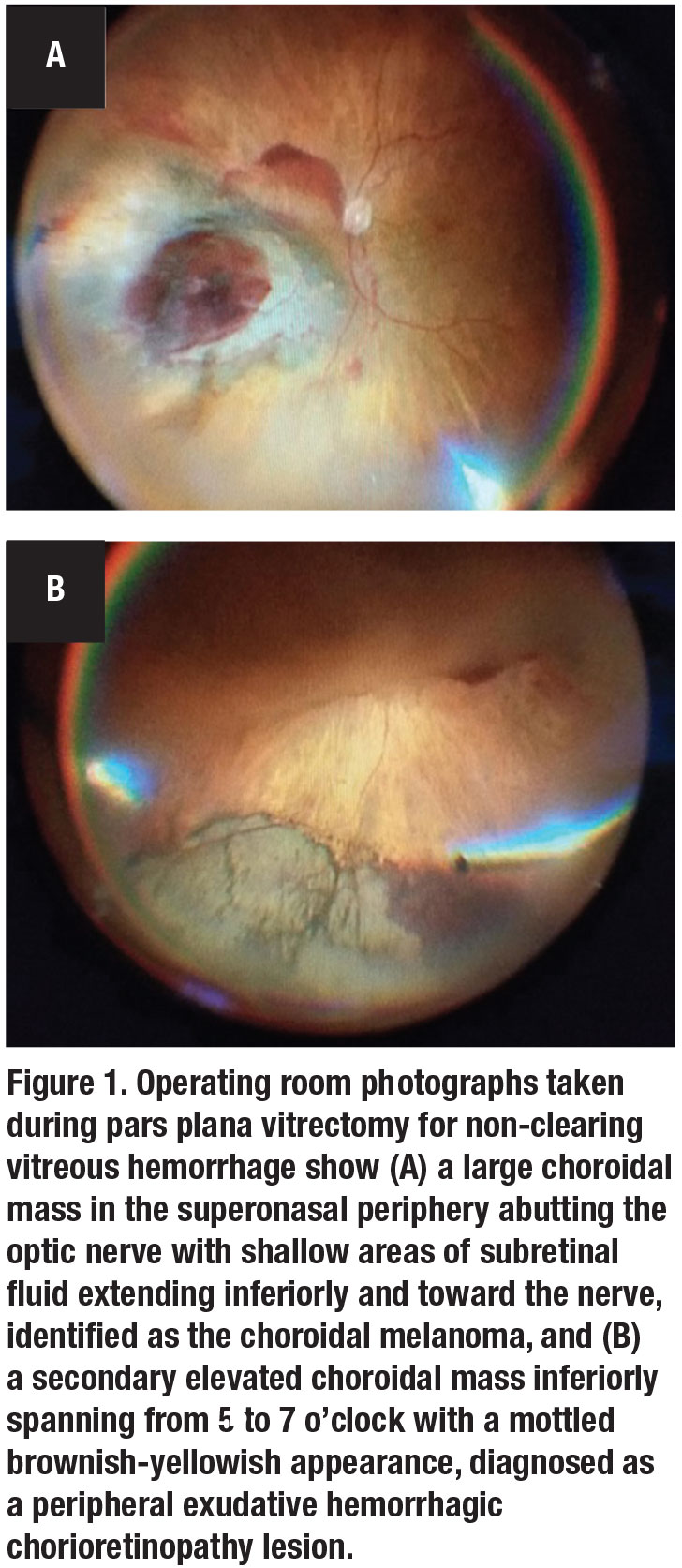

The patient was taken to the operating room for pars plana vitrectomy. A large mass of dehemoglobinized vitreous hemorrhage was present in the central vitreous, which was cleared and shaved into the periphery for 360 degrees. The choroidal melanoma was identified as a large choroidal mass in the superonasal periphery abutting the optic nerve with shallow areas of subretinal fluid extending inferiorly and toward the nerve (Figure 1A).

Unexpectedly, we noted a second elevated choroidal mass inferiorly, spanning from 5 to 7 o’clock with a mottled brownish-yellowish appearance (Figure 1B). This was clinically diagnosed as peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR). We applied a 360-degree endolaser peripheral panretinal photocoagulation to treat presumed radiation retinopathy, sparing the surfaces of the two mass lesions. At the conclusion of the case, we injected a 0.05 mL of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech/Roche) to treat the presumed active choroidal neovascular membrane.

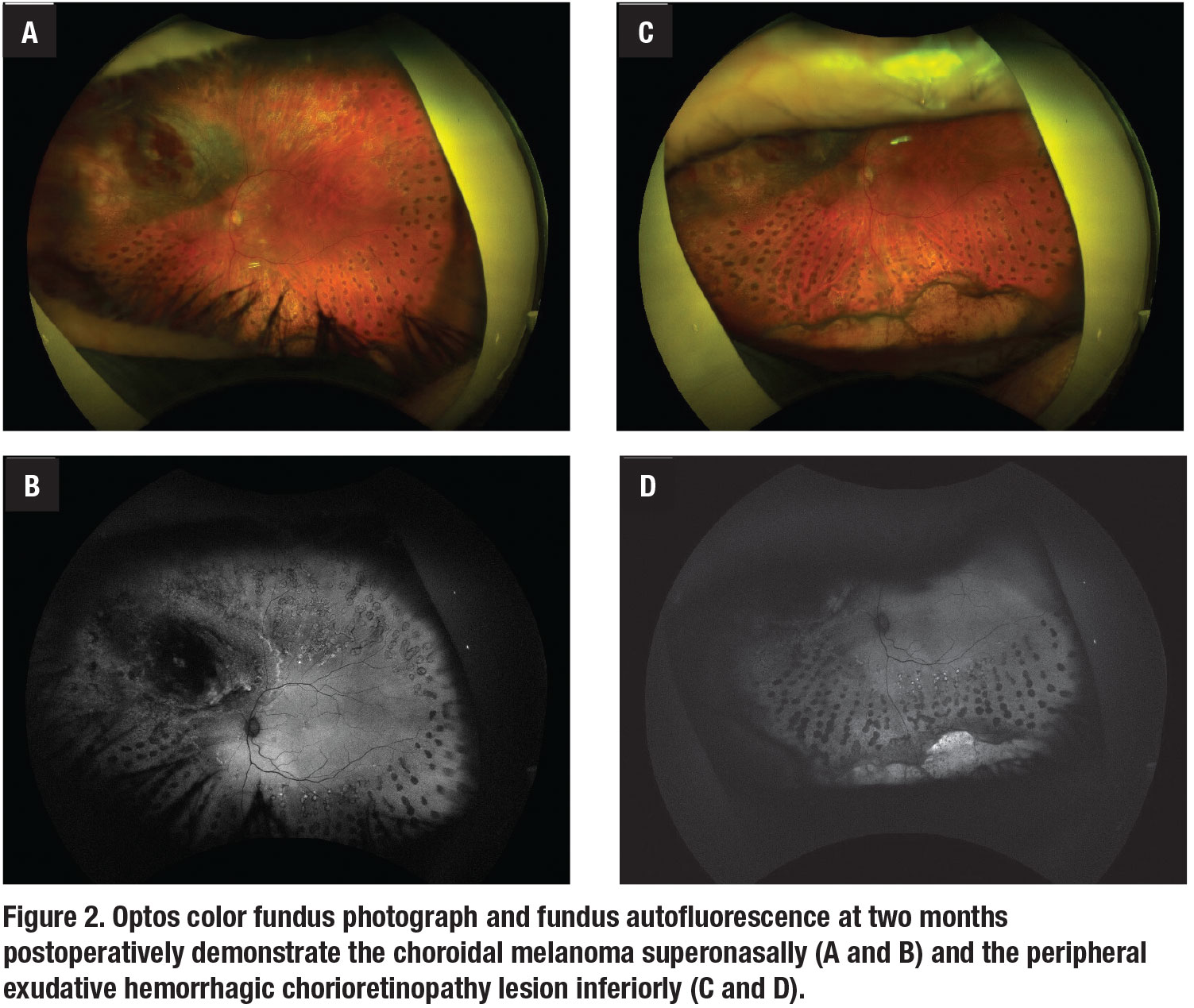

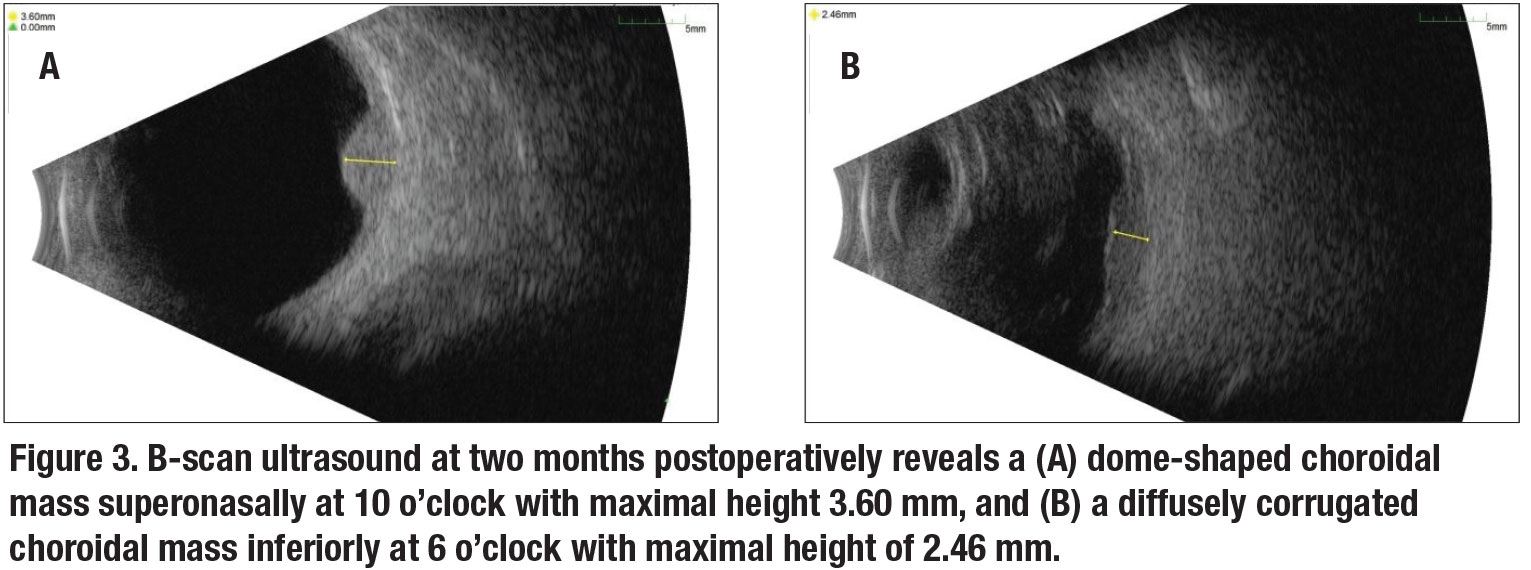

The PEHCR lesion was likely the source of the patient’s large vitreous hemorrhage. At his most recent visit at two months postoperatively, vision was 20/20 in both eyes. Color fundus photos and fundus autofluorescence of the left eye demonstrated the choroidal melanoma superonasally (Figure 2A and B) and the PEHCR lesion inferiorly (Figure 2C and D). B-scan ultrasound of the two lesions showed a dome shaped choroidal mass superonasally at 10 o’clock with maximal height of 3.6 mm (Figure 3A), and a diffusely corrugated choroidal mass inferiorly at 6 o’clock with maximal height of 2.46 mm (Figure 3B).

|

Features of PEHCR

PEHCR is a retinal degenerative process featuring subretinal or subretinal pigment epithelium hemorrhage or exudation. These lesions were first reported in 1961, when Algernon Reese, MD, and Ira Jones, MD, described 34 cases of hematomas under the RPE, of which four cases were peripheral to the macular region.1 In 1980, William Annesley Jr., MD, characterized 32 lesions with blood in the subretinal or sub-RPE space, which he termed “peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy.”2

|

PEHCR is often misinterpreted as an intraocular tumor, in particular choroidal melanoma. Jerry Shields, MD, and colleagues found that 1,739 (14 percent) of 12,000 patients who were referred for evaluation of presumed uveal melanoma actually proved to have a pseudomelanoma.3 In this series, PEHCR (13 percent) was second only to choroidal nevus (49 percent) as the leading category of pseudomelanomas.

In a subsequent study, Carol Shields, MD, and colleagues further investigated the features of PEHCR in 173 eyes of 146 patients referred with the diagnosis of choroidal melanoma.4 The mean patient age was 80 years, and most patients were Caucasian (99 percent) and female (67 percent). The lesions were bilateral in 31 percent.

Patients with PEHCR consistently have systemic hypertension. Dr. Carol Shields and colleagues reported 51 percent of patients in their series had hypertension.4 Dr. Annesley reported 44.4 percent of 27 patients had it,2 and a Swiss study reported 55 percent of 40 patients had hypertension.5

In the series by Dr. Carol Shields and colleagues, a high percentage of patients (42 percent) were asymptomatic, 37 percent had decreased vision and 20 percent had flashes/floaters.4 Thirty-six eyes (21 percent) had decreased visual acuity related to the PEHCR lesion, which was associated with the following presenting symptoms: vitreous hemorrhage in 24 eyes (14 percent); subretinal hemorrhage extending to the macula in eight eyes (5 percent); and subretinal fluid extending to the macula in four eyes (2 percent).

PEHCR lesions are found most commonly in the temporal quadrant, specifically in the inferotemporal quadrant and between the equator and the ora serrata.2,4,5 This is in contrast to choroidal melanomas, which are most commonly located at the macula or between the macula and the equator.6

On ocular ultrasound, PEHCR lesions appear as dome or plateau-shaped elevated lesions. In Dr. Carol Shields’ series, the mean basal dimension was 10.1 mm and the mean thickness was 3 mm.4 The lesions can have hollow, intermediate, solid or irregular acoustic quality. Intravenous fluorescein angiography reveals patchy blockage of choroidal fluorescence related to subretinal hemorrhage, sub-RPE hemorrhage or RPE hyperplasia.4

Observation is appropriate for asymptomatic patients because most PEHCR lesions stabilize or regress with time. Vitrectomy may be indicated for visual impairment due to associated vitreous hemorrhage.

|

Potential role for anti-VEGF

There is no standard of care for patients who become symptomatic due to macular extension of subretinal hemorrhage or fluid. However, anti-VEGF treatment may have potential benefit. A series in Turkey involved 12 eyes with two or three consecutive intravitreal injections of bevacizumab.7 In nine eyes (75 percent), the PEHCR lesions significantly regressed, while in three eyes (25 percent), the lesions extended into the macula despite treatment.

A German series treated nine eyes with an average of three anti-VEGF injections (either 1.25-mg bevacizumab or 0.5-mg ranibizumab [Lucentis, Genentech/Roche]) to achieve complete resolution of macular subretinal fluid.8 In three eyes, subretinal fluid reappeared after an average of 10 months, and 2.5 anti-VEGF injections were necessary to attain complete resolution of macular subretinal fluid for a second time.

Cryotherapy, laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy and intravitreal steroid therapy have all been proposed as potential treatments for PEHCR. However, further investigations are needed to demonstrate the efficacy of these treatments. RS

|

REFERENCES

1. Reese AB, Jones IS. Hematomas under the retinal pigment epithelium. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1961;59:43–69.

2. Annesley WH. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321–364.

3. Shields JA, Mashayekhi A, Ra S, Shields CL. Pseudomelanomas of the posterior uveal tract: The 2006 Taylor R. Smith Lecture. Retina. 2005;25:767-771.

4. Shields CL, Salazar PF, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy simulating choroidal melanoma in 173 eyes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:529-535.

5. Mantel I, Schalenbourg A, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and hemodynamic modifications. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:910-922.

6. Nagori S, Furuta M, Shields CL. Posterior uveal melanoma thickness at diagnosis correlates with tumor location. American Academy of Ophthalmology, New Orleans, Louisiana (2007) November 12–13.

7. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27:111-112.

8. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:653-659.