|

|

Bios Dr. Thomas is a consultant for Allergan/AbbVie, Alimera Sciences, Avesis, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals, Genentech/Roche and Novartis. |

The term “masquerade syndrome” was first used in 1967 to describe a case of conjunctival carcinoma manifesting as a chronic conjunctivitis.1 In uveitis, masqueraders are diseases that can mimic any form of intraocular inflammation. The list of masqueraders is extensive, but here we simplify them into neoplastic and nonneoplastic disorders that we routinely encounter in a retina practice.

Neoplastic masquerade syndromes

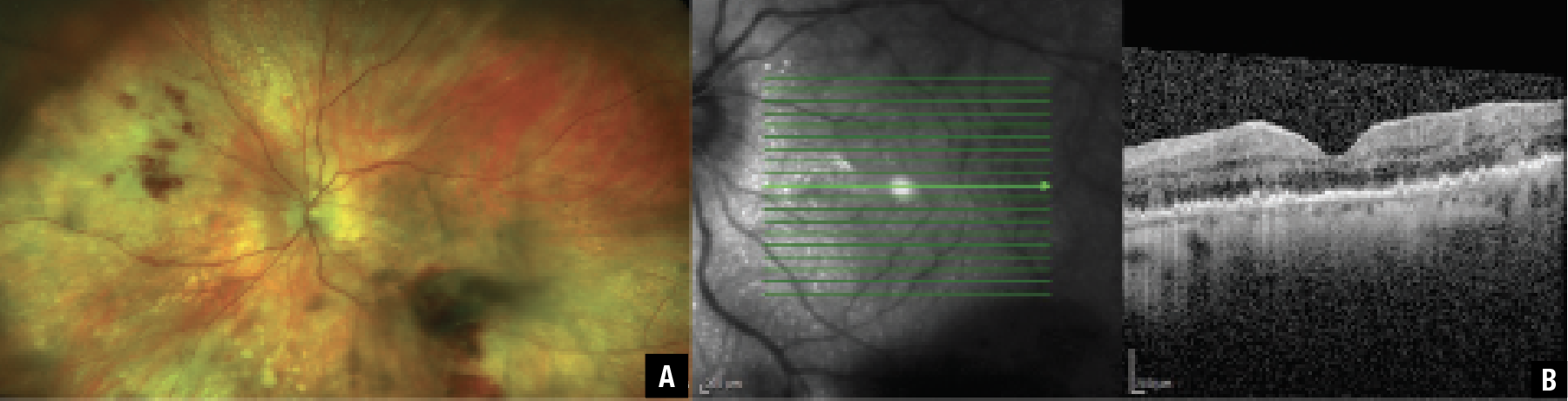

Vitreoretinal lymphoma. VRL is rare but one of the more common intraocular malignancies diagnosed (Figure 1). Its prompt recognition is paramount because up to 90 percent of cases have or will develop central nervous system disease.

VRL represents the most common lymphoma of the eye and it’s more often a diffuse large B-cell subtype, although T-cell lymphomas can occur. Patients often complain of floaters as a presenting symptom. On examination, patients can present with both anterior and intermediate cell and posterior segment findings, including infiltrates below the retinal pigment epithelium.2

Multimodal imaging can be key to making the diagnosis. Characteristic optical coherence tomography findings are RPE nodularity, outer retinal hyper-reflectivity and infiltrates between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane. On fundus autofluorescence, these infiltrates will be hyperautofluorescent. A common pattern on FAF is alternating hypo- and hyperautofluorescence. On fluorescein angiography, these lesions will have a granular appearance with staining and blocking.3

|

| Figure 1. A) Widefield pseudococolor image shows biopsy-proven vitreoretinal lymphoma with vitritis, retinal hemorrhages and multiple areas of varying size circular lesions throughout the periphery. B) Optical coherence tomography highlights the nodular appearance of the retinal pigment epithelium and infiltrates between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane. (Courtesy Johnathan A. Gonzales, MD). |

The diagnosis is made with intraocular specimens from an anterior chamber paracentesis or, more routinely, a vitreous biopsy. Direct visualization of lymphoma cells on cytopathology is the gold standard for diagnosis, but many tests can support the diagnosis of VRL. They include aqueous and vitreous analysis of interleukin (IL)-10 levels and IL-10 to IL-6 ratios, flow cytometry and myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 testing.4

A retinal biopsy can be considered when the vitreous biopsy is negative but clinical suspicion remains high. It’s important that a patient hasn’t received systemic or local corticosteroids preoperatively; these will increase the yield of lymphoma cells. Deep sequencing is an emerging technology that may be another technique to add to our armamentarium to aid in the diagnosis of lymphoma.5

Treatment includes a multidisciplinary team with oncology and can include both local therapy with intravitreal methotrexate or rituximab and systemic chemotherapy.

Uveal lymphoma. Also of B-cell origin, uveal lymphomas can affect the iris, ciliary body and choroid. Like VRL, they respond to steroid treatment, but their nature is far more indolent. A yellow-pink choroidal infiltration is notable on clinical exam, but thickening of the uveal tract appears later in the disease.6 The appearance of infiltrative choroidal lesions beneath Bruch’s membrane is a key OCT finding in uveal lymphoma that helps differentiate it from VRL.3

Leukemia. Up to 90 percent of patients with a diagnosis of leukemia can have ocular involvement.7 While posterior-segment involvement can result from retinal infiltration of neoplastic cells, it can also result from secondary causes such as anemia or hyperviscosity. The retinal manifestations, such as Roth spots, cotton wool spots, venous dilation and vessel tortuosity, can be extensive. However, from a uveitis standpoint, leukemia can manifest as an angiopathy that can resemble a frosted branch angiitis. It can also mimic a hypopyon uveitis and even an intermediate uveitis.8

Retinoblastoma. RB represents the most common pediatric intraocular tumor. Particularly, the diffuse subtype presents as a flat, ill-defined mass which can cause a pseudohypopyon masquerading as an anterior uveitis. Additionally, the disease can present with findings of a posterior uveitis, which makes the diagnosis challenging. Indeed, in one study 9 percent of referrals to a clinical service were for uveitis when in fact the true diagnosis was RB.9

Metastatic tumors. Given the vascular nature of the choroid, it’s no surprise that it represents the most common site for metastasis of systemic solid tumors. The metastasis is typically from the breast or lung. These lesions typically present as creamy white or yellow retinal masses with subretinal fluid and retinal hemorrhage.10 Metastasis may involve other uveal structures, such as the iris and ciliary body, which can present with an anterior uveitis.11

Paraneoplastic retinopathy. This includes diseases such as cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR) and melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR). Paraneoplastic retinopathy falls under the purview of a paraneoplastic syndrome, which is defined as “signs and symptoms observed from cancer but not directly as a cause of the cancer tissue or its associated sites of metastasis.”12

Examination findings include anterior and vitreous cell, and vascular attenuation. OCT may demonstrate outer retinal loss, which could mimic a uveitis syndrome.13 If suspicion for paraneoplastic retinopathy is high, seek out the source malignancy with whole-body imaging and ensure the patient has had age-appropriate cancer screening.

Non-neoplastic masquerade syndromes

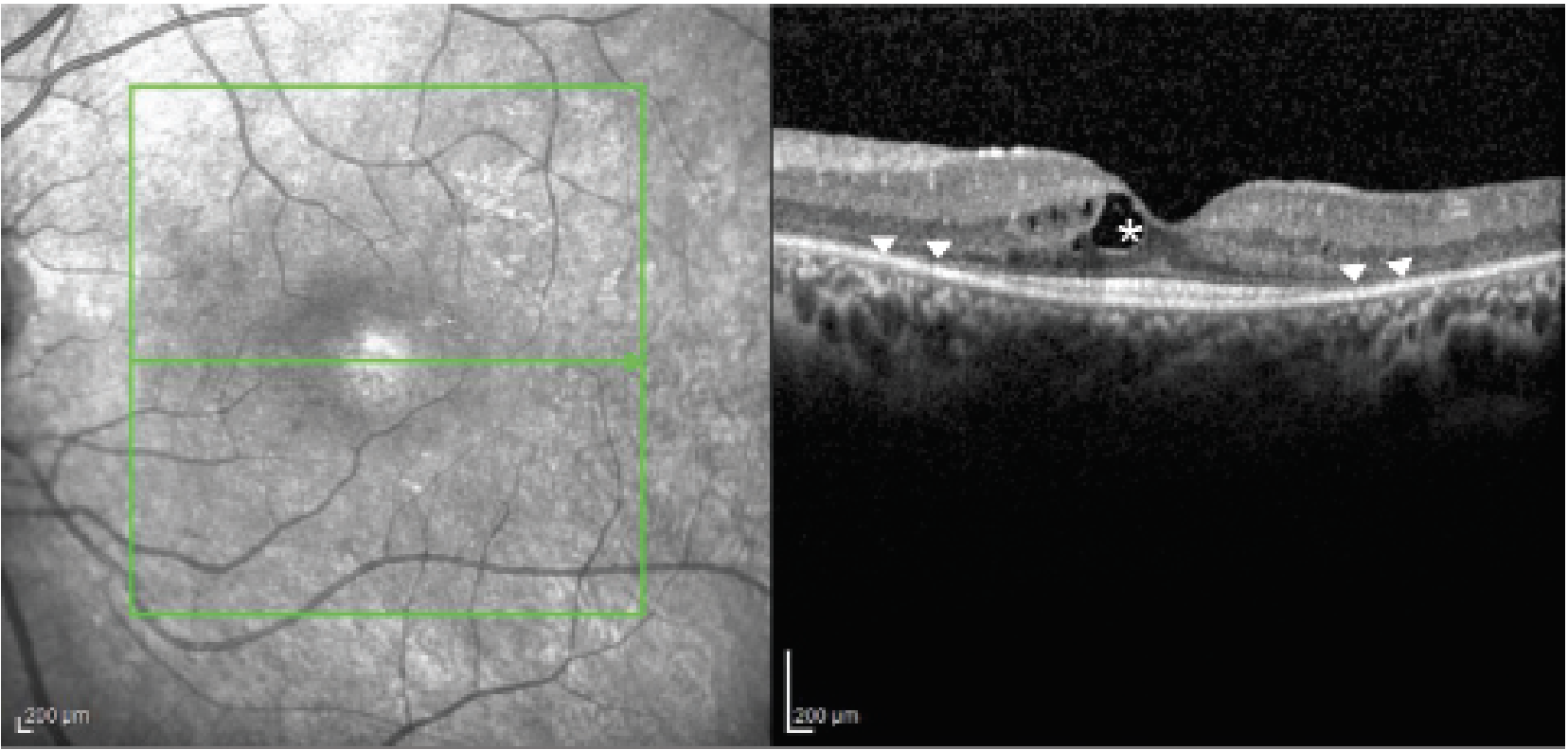

Retinitis pigmentosa. The classic triad for RP includes waxy pallor of the optic disc, retinal pigmentary changes and arteriolar attenuation (Figure 2). RP patients can present with cystic macular edema and also have vitreous cell—the result of photoreceptor death14—with RPE changes that can often disguise themselves as an intermediate and posterior uveitis.

|

| Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography image of retinitis pigmentosa demonstrating cystic macular edema (asterisk) and outer retinal loss (arrow heads). |

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Like uveitis, retinal detachments can present with hypotony. Given the presence of cell and pigment, it’s important to carefully exclude a far peripheral detachment as a cause for a patient’s presumed inflammation. Conversely, Schwartz-Matsuo syndrome can present with cell and elevated intraocular pressure (secondary to blockage of the trabecular meshwork by outer segments of the photoreceptors), which could mimic a hypertensive anterior uveitis.15

Intraocular foreign bodies. While IOFBs are easy to recognize and mitigate when entry wounds are present and a patient’s history is accurate, the insult can go unrecognized and their onset can be insidious in some cases, particularly with metallic foreign bodies. This can lead to masquerade signs of conjunctival injection, pigment and anterior-segment cell and flare, all of which could be mistaken for uveitis.16

Syphilis. While uveitis clinics commonly test for the great masquerader syphilis as an infectious etiology, its ocular manifestations are vast and merit placement on this list. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends both treponemal testing—fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, the T. pallidum passive particle agglutination assay, various enzyme immunoassays, chemiluminescence immunoassays and immunoblots—and nontreponemal testing, namely Venereal Disease Research Laboratory or rapid plasma reagin.

Ordering only one serologic test is insufficient for diagnosis. A treponemal test is necessary to confirm disease while a nontreponemal test can help to monitor disease activity and gauge treatment response.17

A 2017 meta-analysis found the optic nerve was the most frequently affected ocular structure, presenting as papillitis, neuritis or neuroretinitis, but that syphilis can present as an anterior or intermediate uveitis as well. While posterior placoid choroiditis can be seen, so can vasculitis and retinitis.18 Directed testing to rule out syphilis is a must whenever a patient presents with uveitis.

Bottom line

Masqueraders can mimic any form of ocular inflammation. Separating them into neoplastic and nonneoplastic etiologies can help us to identify these pathologies promptly and spare our patients from debilitating vision loss. RS

REFERENCES

1. Theodore FH. Conjunctival carcinoma masquerading as chronic conjunctivitis. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1967;46:1419–1420.

2. Chan CC, Rubenstein JL, Coupland SE, et al. Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: A report from an International Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Collaborative Group symposium. Oncologist. 2011;16:1589-1599.

3. Xu LT, Huang Y, Liao A, et al. Multimodal diagnostic imaging in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Int J Retin Vitr. 2022;8:58.

4. Pulido JS, Johnston PB, Nowakowski GS, Castellino A, Raja H. The diagnosis and treatment of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: A review [published correction appears in Int J Retina Vitreous. 2018;4:22]. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2018;4:18.

5. Gonzales J, Doan T, Shantha JG, et al. Metagenomic deep sequencing of aqueous fluid detects intraocular lymphomas. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:6-8.

6. Biscotti CV, Singh AD (eds): FNA Cytology of Ophthalmic Tumors. Monographs in Clinical Cytology. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2012; 21:31–43.

7. Kincaid MC, Green WR. Ocular and orbital involvement in leukemia. Surv Ophthalmol. 1983;27:211-232.

8. Talcott KE, Garg RJ, Garg SJ. Ophthalmic manifestations of leukemia. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27:545-551.

9. Shields CL, Ghassemi F, Tuncer S, Thangappan A, Shields JA. Clinical spectrum of diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma in 34 consecutive eyes. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:2253-2258.

10. Mathis T, Jardel P, Loria O, et al. New concepts in the diagnosis and management of choroidal metastases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019;68:144-176.

11. Kesen MR, Edward DP, Ulanski LJ, Tessler HH, Goldstein DA. Pulmonary metastasis masquerading as anterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:572–574.

12. Rahimy E, Sarraf D. Paraneoplastic and non-paraneoplastic retinopathy and optic neuropathy: Evaluation and management. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58:430-458.

13. Przezdziecka-Dołyk J, Brzecka A, Ejma M, et al. Ocular paraneoplastic syndromes. Biomedicines. 2020;8:490.

14. Olivares-González L, Velasco S, Campillo I, Rodrigo R. Retinal inflammation, cell death and inherited retinal dystrophies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2096.

15. Etheridge T, Larson JC, Nork TM, Momont AC. Schwartz-Matsuo syndrome: An important cause of secondary glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2020;17:100586.

16. Akal A, Goncu T, Atas M, Demircan S, Ozkan U, Yuvaci I. A case of treatment-resistant uveitis with intraocular foreign body. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2014;4:272-273.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis - STI treatment guidelines. Atlanta, GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. Updated March 30, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm . Accessed January 3, 2023.

18. Zhang T, Zhu Y, Xu G. Clinical features and treatments of syphilitic uveitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:6594849.