|

|

|

With anti-VEGF therapy patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration typically have significant improvements in visual acuity and quality of life. While the short-term results are nothing short of spectacular, several important questions regarding long-term management of these patients persist. They include:

- Which is the best agent?

- How often should one treat?

- Does long-term dosing of these agents cause vision loss and damage?

- Are new platforms on the horizon for long-term delivery of these agents?

- This article answers those questions based on findings of pivotal clinical trials.

Are all anti-VEGF agents equal? How often should we treat?

In 2006, the landmark ANCHOR and MARINA studies demonstrated the efficacy and safety of monthly ranibizumab (Lucentis, Roche/Genentech) with monthly dosing. Patients gained 10.7 and 6.6 letters, respectively, at two years.1-2 Subsequently, the parallel VIEW1 and VIEW2 studies showed mean improvement in vision at two years with aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) q8 weeks after three initial monthly loading doses.3

Subsequent trials allowed us to evaluate the efficacy of these drugs employing less frequent dosing intervals including quarterly, pro re nata (PRN) and treat-and-extend regimens. The PIER study examined quarterly dosing with ranibizumab after three monthly loading doses, and, while superior to observation, PIER patients lost 2.3 letters from baseline at one year.4

|

One of the earliest exceptions was PrONTO, a Phase I/II trial that evaluated 40 patients over two years with monthly monitoring and PRN retreatment based on visual acuity, clinical examination and optical coherence tomography parameters.5 The visual acuity results approached those of ANCHOR and MARINA with nearly half the number of injections, but the study lacked a monthly treatment control arm. These results have not been duplicated in subsequent PRN trials.

The HARBOR trial compared monthly and PRN dosing of ranibizumab. The monthly 0.5-mg group gained 9.1 letters at 24 months vs. 7.9 letters for the PRN group. While this difference was not statistically significant, the median number of injections (but not the number of visits) was reduced from 21.4 to 13.3.6

CATT and IVAN were similar studies that compared monthly and PRN dosing of ranibizumab and off-label bevacizumab (Avastin, Roche/Genentech). At two years, PRN dosing was found to be noninferior to monthly treatment in both studies (except for PRN bevacizumab in CATT), although there was a trend toward better vision in the monthly groups.7,8

TREX compared monthly ranibizumab to a treat-and-extend (T&E) regimen.9 Once again, the visual acuity difference wasn’t statistically significant (10.5 in the monthly group and 8.7 in the T&E group), but trended toward better vision in the monthly group. The mean number of injections was 25.5 vs. 18.6 over two years. Also, no monthly cohort patients lost more than 2 letters, while five T&E patients lost at least 3 lines of vision.

While these studies have shown statistically similar results with monthly dosing in the short term, absolute data outcomes have been almost unanimously superior with monthly dosing of anti-VEGF agents.

What happens after two years?

The data beyond two years from these clinical trials aren’t as easy to interpret and apply as the clinical trial data, primarily because these extension studies mainly evaluated long-term drug safety. So, the follow-up and treatment schedules were not as rigorous.

|

HORIZON was the extension study for patients in the MARINA, ANCHOR and FOCUS trials. These patients didn’t follow a protocol; they received treatment at the investigators’ discretion during evaluation visits every three to six months. At four years, HORIZON patients essentially lost the initial VA gains and regressed to baseline vision (-0.1 letters).10 Further data analysis found an association between better vision and more injections.

The CATT five-year study assessed patients monitored and treated at the investigators’ discretion after the first two years of the trial. On average, patients lost 3 letters compared to baseline vision. Patients were seen an average of eight times per year and received an average of five treatments per year.11 Some discussion ensued as to whether the vision loss was due to undertreatment or development of macular atrophy, but the trial wasn’t powered to tease out this difference.12

The VIEW 1 extension study monitored patients more rigorously. Participants received fixed-interval >q8-week dosing, but they could receive more frequent treatments if they met prespecified criteria. In this extension, patients retained much better vision, with mean vision of gain 7.1 letters from baseline (compared with a 10.4-letter gain at the one-year primary endpoint).13

What happens in the long-term and does dosing frequency matter?

|

The best long-term data we have is from observational studies. The SEVEN-UP Study was an extension of the ranibizumab trials. Although there was no prespecified visit schedule or injection protocol, the data provide some information. At seven years, patients on average lost 8.6 letters from baseline. Patients receiving no injections over the subsequent three years lost 8.7 letters from baseline; those receiving one to five injections lost 10.8 letters; those having six to 10 injections lost 6.9 letters; and those receiving more than 11 injections gained 3.9 letters from baseline.14

The Fight Retinal Blindness Study Group from Australia observed patients treated with anti-VEGF for seven years. These patients lost an average of 2.6 letters from baseline, having received an average of five injections a year after year two, when they had gained 4 letters from baseline.15

Finally, the FIDO study was a single-center observational study using q4-week fixed-dosing for the first two years and >q8 weeks beyond that. These patients gained 12.1 letters from baseline (from a peak of 16.1 letters at two years) with an average of 10.5 injections per year.16

The central message from these long-term observational studies is that clearly, on average, more injections translated into better vision.

|

We now have 10-year data

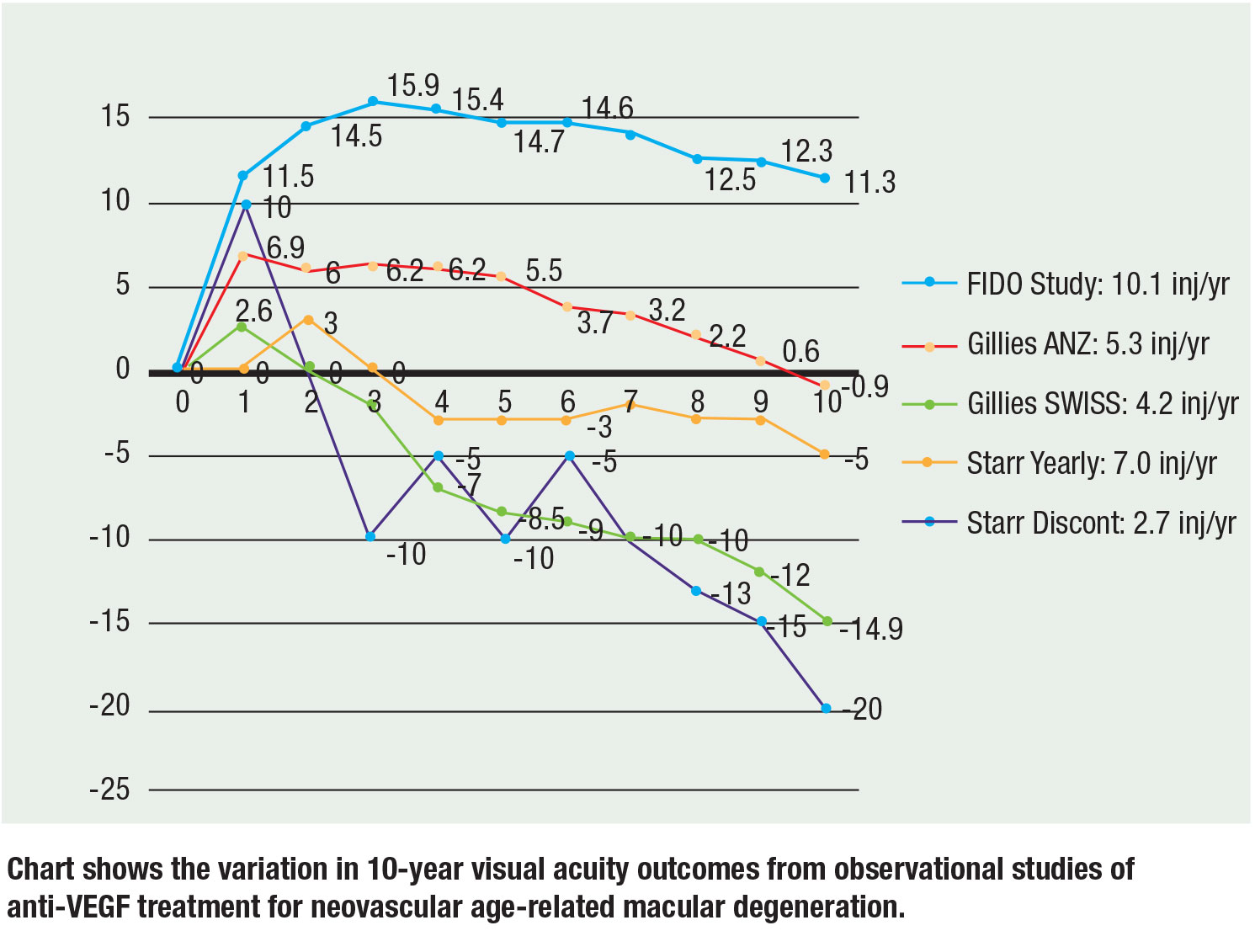

Recently, three large observational studies have reported 10-year data and the results remain consistent: More injections translate to better visual acuity. Mark Gillies, MD, and colleagues reported observational data from Australia-New Zealand and Switzerland. In the ANZ patients, mean vision decreased by 0.9 letters from baseline at 10 years with a median of 5.3 injections/year on a T&E regimen compared to the Swiss patients, whose vision decreased by a mean of 14.9 letters with a median of 4.2 injections per year on PRN. Their conclusion was that continuous treatment and more injections achieved better vision.17

Matthew Starr, MD, and colleagues evaluated a cohort that included patients who had at least two injections. On average, the patients received five to seven injections a year. Eyes receiving at least one injection a year lost approximately 7 letters from baseline, whereas eyes that didn’t receive at least a yearly injection lost 15 letters from baseline.18

Our 10-year FIDO cohort achieved a mean increase in vision of 11.3 letters from a peak of 15.9 with an average of 10.1 injections per year over the study period.19

It’s important to note that there are inherent risks with cross-trial comparisons given different initial visual acuity and patient populations, but the slopes and trends hold to the correlation of more injections with better vision. The figure (page 29) summarizes 10-year data from the three trials.

Does frequent treatment result in progression to geographic atrophy?

The worry of geographic atrophy progression with anti-VEGF treatment has been a concern and a frequently invoked rationale for not treating frequently. Some evidence suggests that the risk of vision loss from undertreatment far outweighs this potential concern. The SEVEN-UP trial showed greater incidence of GA in fellow eyes than in eyes treated with anti-VEGF.14

Furthermore, the FIDO 10-year data demonstrated a slightly lower incidence of GA with vision loss at 10 years in the treated eyes compared to untreated fellow eyes (15 vs. 19 percent).19 It’s likely that the progression of true GA is independent of

anti-VEGF treatment, and what is observed is drying-out of the neovascular complex that looks like GA but with a less-deleterious impact on vision.

Bottom Line

Continuous, regular treatment with anti-VEGF agents provides outstanding results in the management of wet AMD. The long-term data demonstrate that risk of vision loss is greater from undertreatment than from continuous treatment at regular intervals as currently applied in fixed-interval dosing or conservative treat-and-extend regimens. Long-term delivery platforms such as the port-delivery system and gene therapy appear promising in decreasing the barriers of noncompliance, burden of frequent visits and challenges of variable individual dosing requirements. RS

References

1. Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432-1444.

2. Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. MARINA Study Group, Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419-1431.

3. Schmidt-Erfurth U, Kaiser PK, Korobelnik JF, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: ninety-six-week results of the VIEW studies. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:193-201.

4. Regillo CD, Brown DM, Abraham P, et al. Randomized, double-masked, sham-controlled trial of ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: PIER Study year 1. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:239-248.

5. Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, Fung AE, et al. A variable-dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: year 2 of the PrONTO Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:43-58.

6. Ho AC, Busbee BG, Regillo CD, et al, for the HARBOR Study Group. Twenty-four-month efficacy and safety of 0.5 or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2181-2192.

7. Martin DF, Maguire MG, Fine SL, et al, for the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1388-1398.

8. Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, et al. Alternative treatments to inhibit VEGF in age-related choroidal neovascularization: 2-year findings of the IVAN randomized control trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1258-1267.

9. Wykoff CC, Ou WC, Brown DM, et al. Randomized trial of treat-and-extend versus monthly dosing for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: 2-year results of the TREX-AMD study. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;1:314-321.

10. Singer MA, Awh CC, Sadda S, et al. HORIZON: An open-label extension trial of ranibizumab for choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1175-1183.

11. Maguire MG, Martin DF, Ying GS, et al. Five-year outcomes with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: The comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1751-1761.

12. Grunwald JE, Pistilli M, Ying GS, et al. Growth of geographic atrophy in the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:809-816.

13. Kaiser PK, Singer M, Tolentino M, et al. Long-term safety and visual outcome of intravitreal aflibercept in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;1:304-313.

14. Rofagha S, Bhisitkul RB, Boyer DS, Sadda SR, Zhang K, for the SEVEN-UP Study Group. et al. Seven-year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON: A multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2292-2299.

15. Gillies MC, Campain A, Barthelmes D, et al, for the Fight Retinal Blindness Study Group. Long-term outcomes of treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Data from an observational study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1837-1845.

16. Peden MC, Suñer IJ, Hammer ME, Grizzard WS. Long-term outcomes in eyes receiving fixed-interval dosing of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents for wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:803-808.

17. Gillies M, Arnold J, Bhandari S, et al. Ten-year outcomes of neovascular age-related macular degeneration from two regions. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;210:116-124.

18. Starr MR, Kung FF, Bui YT, et al. Ten-year follow-up of patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration treated with intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections. Retina. Published online November 13, 2019.

19. Suñer IJ, Peden MC, Hammer ME, Grizzard WS. Ten-year outcomes in eyes receiving fixed-interval dosing of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents for wet age-related macular degeneration. Paper presented at Retina Society 2019; September 12, 2019; London, U.K.

20. Campochiaro PA, Marcus DM, Awh CC, et al. The port delivery system with ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: results from the randomized phase 2 LADDER clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:1141-1154.

21. Ho AC; the Janssen/ORBIT Study Group. Precision delivery programs for cell and gene therapy. Paper presented at: Vail Vitrectomy Meeting; February 10, 2019; Vail, CO.

22. ADVM-022 gene therapy for wet AMD (OPTIC). Sponsor: Adverum Biotechnologies. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03748784. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03748784. Accessed April 18, 2020.

23. RegenxBio reports first quarter 2019 financial and operating results and additional positive interim phase I/IIa trial update for RGX-314 for the treatment of wet AMD [press release]. Rockville, MD; May 7, 2019. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/regenxbio-reports-first-quarter-2019-financial-and-operating-results-and-additional-positive-interim-phase-iiia-trial-update-for-rgx-314-for-the-treatment-of-wet-amd-300845423.html Accessed July 9, 2020.