New Insights in Imaging

Take-home points

|

|

|

Bios Dr. Hamdan is a research fellow at the Cole Eye Institute of the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Mammo, Dr. Sharma and Dr. Srivastava specialize in uveitis and vitreoretinal diseases at Cole Eye Institute. Dr. Srivastava is also director of vitreoretinal fellowships. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Hamdan has no relevant relationships to disclose. Dr. Mammo served on an advisory board for Alimera Sciences. Dr. Srivastava disclosed relationships with Bausch + Lomb, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, jCyte, Adverum Biotechnologies, Zeiss, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals and Eyevensys. Dr. Sharma disclosed relationships with Allergan/AbbVie, EyePoint, Clearside Biomedical, Bausch + Lomb, Genentech/Roche, Regeneron, RegenxBio, Apellis IONIS, Santen and Gilead. |

Vitreoretinal lymphoma presents multiple diagnostic challenges because of its atypical clinical presentation, which may include misleading initial response to steroids and false-negative biopsies. As a masquerade syndrome, vitreoretinal lymphoma requires a high suspicion and reliance on good cytopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Clinicians have historically used vitreous biopsies and fine-needle aspiration biopsies (FNAB) to diagnose inflammatory, neoplastic or infectious ocular diseases in the posterior segment because these methods provide good accessibility and a low likelihood of complications.1-8

Nonetheless, when vitreous sampling or FNAB is inconclusive, more invasive techniques, such as retinal or subretinal pigment epithelium biopsies, may be warranted. Here, we present two cases that demonstrate the utility of these techniques.

Case 1: Worsening floaters and dry AMD

A general ophthalmologist saw an 82-year-old White phakic male for chronic worsening floaters in both eyes. His ocular history included non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration in both eyes and a right posterior vitreous detachment. His medical history was significant for prostate cancer status post-radiation and resection.

Visual acuity on initial presentation was 20/30 OU. The slit lamp exam demonstrated no anterior chamber or vitreous cells. Optical coherence tomography imaging at this time demonstrated drusen and rare subretinal deposits we interpreted to be consistent with drusen.

The patient had subsequent cataract surgery in the right eye. While on a topical steroid taper during the postoperative course, he was referred to the retina service for new white lesions in the right eye.

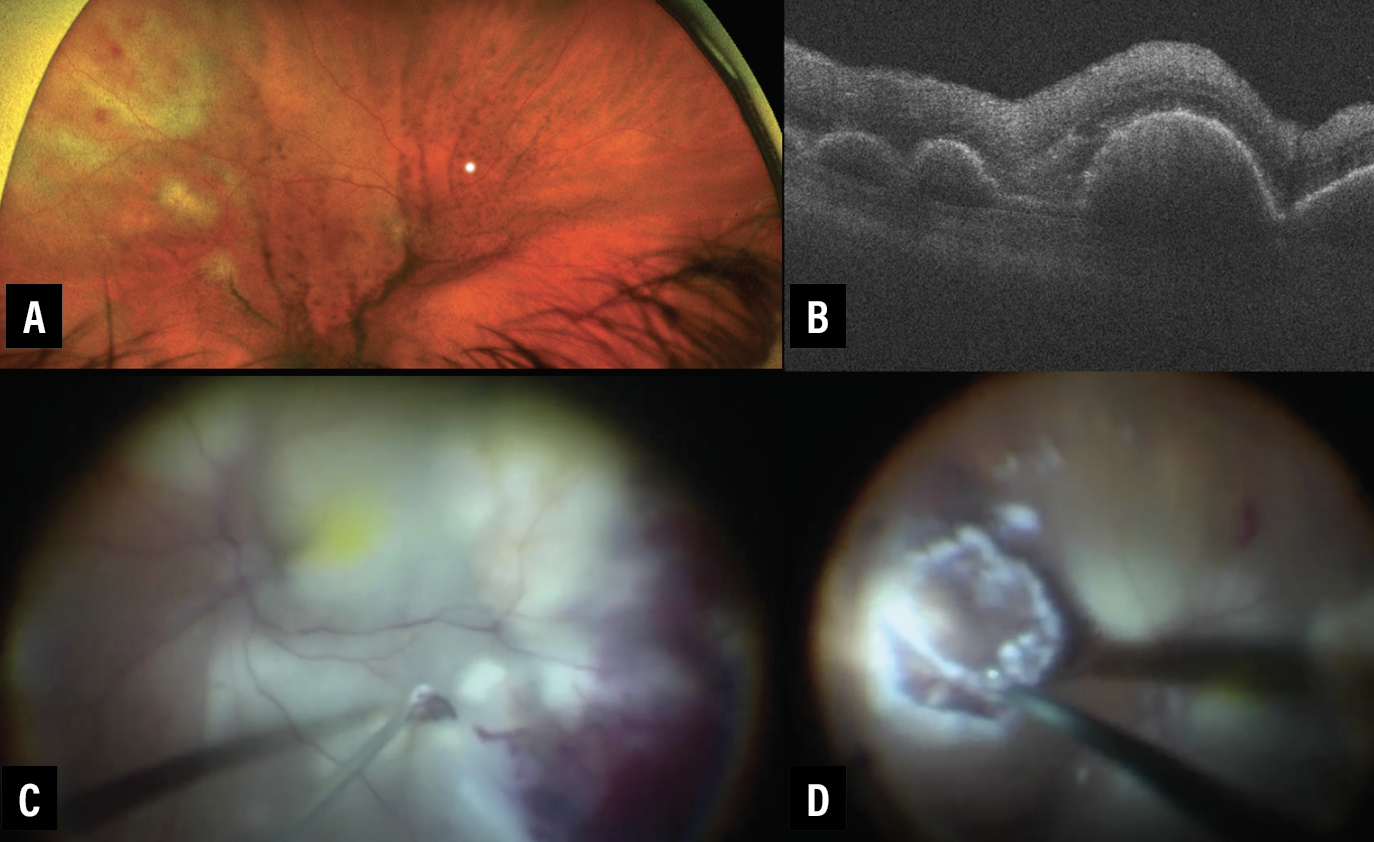

Decline in VA. Visual acuity declined rapidly from 20/50 to 20/500 within two weeks. Slit lamp and fundus examinations were significant for 3+ vitreous cell OD in clumps/sheets with superotemporal retinal whitening and elevation (Figure 1A). OCT demonstrated RPE thickening and hyperreflective subretinal infiltrates (Figure 1B). Inflammatory and infectious lab workups were unremarkable. A brain MRI showed no lesions.

A diagnostic pars plana vitrectomy was performed with only vitreous biopsy. Cytology and flow cytometry revealed no malignant cells. However, suspicion remained high for vitreoretinal lymphoma.

Neurological symptoms worsen. A full-thickness retinal biopsy was scheduled, although before the patient returned to the operating room, he developed worsening neurological symptoms and was admitted, whereupon a new brain MRI (just two weeks after the prior) demonstrated multifocal areas of bilateral signal abnormality suspicious for primary CNS lymphoma.

Lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid studies were inconclusive. These new findings prompted an even higher suspicion of vitreoretinal lymphoma. The patient’s primary-care team helped clear him to undergo an additional diagnostic vitrectomy with a full thickness retinal/RPE biopsy.

At the time of this surgery, his fundus appearance had worsened significantly (Figure 1C). The vitreous aspirate was inconclusive again, yet pathology of the subretinal (Figure 1C) and retinal and sub-RPE tissue (Figure 1D) revealed aggressive large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The patient was started on systemic rituximab and methotrexate. Within two weeks he was transferred to the intensive-care unit for increasing lethargy, and was later transferred to hospice.

|

| Figure 1. A) Optos widefield photograph of right eye demonstrates vitreous debris in clumps and sheets with superotemporal subretinal whitening and elevated lesions. B) Optical coherence tomography through the lesions demonstrates retinal pigment epithelium thickening and hyperreflective subretinal infiltrates. C) At the time of pars plana vitrectomy, the fundus appearance had significantly worsened with large areas of subretinal whitening and elevation. A subretinal aspiration biopsy is visualized with the 25-gauge cutter. D) Visualization of a full-thickness retinal and sub-RPE biopsy. |

Case 2

A 42-year-old male with no significant medical history presented through an outside referral with a decline in vision OS to 20/400. A diagnostic vitrectomy by an outside provider was negative.

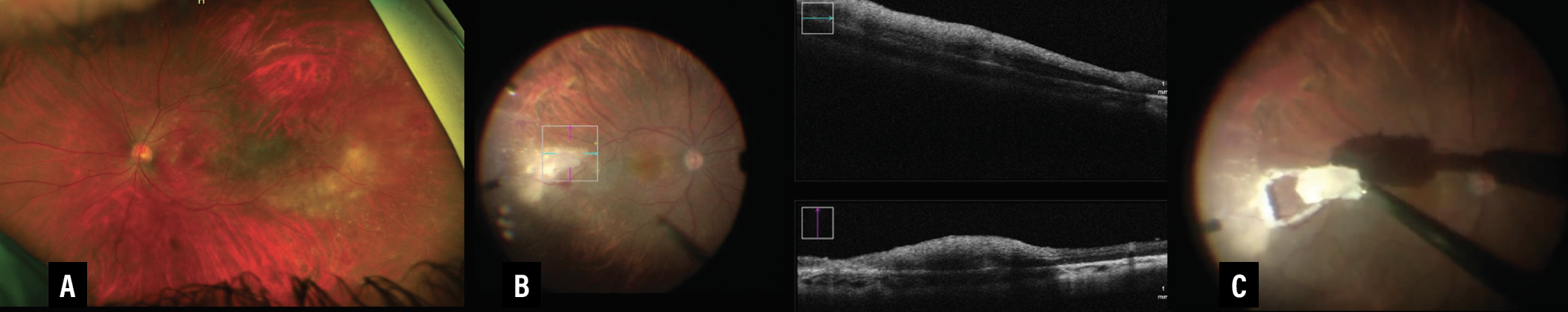

He presented with 1+ vitreous cells, clumps of vitreous debris, subretinal macula deposits, inferotemporal retinal whitening, vascular sheathing, and peripheral exudates (Figure 2A). OCT OS demonstrated ellipsoid zone mottling and subretinal hyperreflective deposits, which were greatest temporally.

Fundus autofluorescence demonstrated mostly hypoautofluorescence with some areas of hyperautofluorescence. Fluorescein angiography demonstrated significant vascular leakage around the subretinal lesions and greater leakage in the area of full-thickness retinal involvement inferotemporally with peripheral nonperfusion. Outside lab testing for syphilis antibodies and tuberculosis (QuantiFERON Gold) were negative. A brain MRI was also normal.

Intraoperative OCT showed full-thickness retinal involvement without significant subretinal/RPE involvement (Figure 2B). Despite the previous negative diagnostic vitrectomy at the outside hospital, these findings gave rise to a higher suspicion for vitreoretinal lymphoma, requiring a repeat diagnostic vitrectomy with full-thickness retinal/RPE biopsy.

|

| Figure 2. A) Optos widefield photograph of the left eye demonstrates vitreous debris, subretinal macular deposits, inferotemporal retinal whitening, vascular sheathing and peripheral exudates. B) Intraoperative optical coherence tomography shows full-thickness retinal involvement without significant subretinal/retinal pigment epithelium involvement. C) We performed a full-thickness retinal and sub-RPE biopsy. |

The vitreous aspirate was negative on cytology and flow cytometry for a malignant process. In contrast, the full-thickness retinal and RPE biopsy (Figure 2C) revealed evidence of a large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The patient returned to his outside institution with the tissue-proven diagnosis and began systemic and local chemotherapy.

Vitreous collection with PPV or FNAB

Vitreoretinal surgeons have several methods available for acquiring diagnostic tissue, including vitreous biopsies, FNABs and retinal/subretinal biopsies.

Because of its relatively low invasiveness, vitreous collection continues to be a standard diagnostic procedure for inflammatory disorders affecting the posterior segment.5 Vitreous can be acquired through a PPV or a FNAB. It’s typically done as a primary surgery and, theoretically, carries a decreased risk of complications compared to retinal/choroidal biopsies.5

In PPV, the vitreous sample is collected through aspiration into a syringe across a broken aspiration line while the cutter is activated.5 In contrast, FNAB involves insertion of a needle and syringe through the pars plana. FNAB isn’t recommended primarily for vitreous aspirate because of insufficient cellularity, although it could be a reasonable option for retinal, RPE or choroidal biopsy.5

Vitreous samples can be obtained in both undiluted and diluted forms for cytology and flow cytometry, respectively. Other options include polymerase chain reaction (PCR, MYD88 or viral), cytokine rearrangement, metagenomic sequencing, and microbial/fungal microscopy and culture.1,6

Fixate extracted cells quickly. Cells extracted from the vitreous should be quickly fixated or placed in tissue culture because they’re susceptible to rapid degeneration. We greatly encourage effective collaboration with a cytopathologist.5 We immediately place the sample into fixative to reduce the risk of cellular degeneration, followed by prompt transportation directly to the cytopathology lab.

Postoperative complications associated with vitreous biopsies include false-negative results, hemorrhage, retinal detachment, needle-tract seeding and endophthalmitis.5

Retinal/choroidal biopsies

One of the most common indications for retinal/choroidal biopsies is atypical uveitis refractory to treatment, especially when a rare neoplastic or infectious etiology is suspected. In highly suspicious cases, full-thickness biopsies can also be considered during the initial diagnostic procedure.1,2 These cases often have inconclusive vitreous biopsies, brain MRI studies and lumbar punctures, further requiring a definitive diagnosis to initiate treatment. Retinal/choroidal biopsies may either provide a definitive diagnosis or at least exclude infectious and malignant causes to enable more targeted therapy.1,2

|

Key steps for retinal/choroidal biopsies. Retinal/choroidal biopsies begin with a vitreous sample through a PPV, as we described.5 Perform endodiathermy of the retinal vessels surrounding the biopsy after completing the vitrectomy and then define the biopsy site with a diode laser and/or full-thickness diathermy. Curved horizontal scissors, vertical scissors, pneumatic vertical scissors or a small-gauge vitreous cutter may be used to remove the tissue.

Postdissection, leave a small segment of retina attached at the base so the tissue isn’t lost due to fluidic changes. Create or extend a full-thickness sclerotomy. Forceps, grasping at the tissue base, enable withdrawal of the specimen through the sclerotomy. A fluted, large-bore needle attached to suction or a syringe are alternative options for extraction.

Encircling the biopsy site. You may encircle the biopsy site with additional endolaser and long-acting gas or silicone oil tamponade if needed.5 We tend to aim for the thickest part of the lesion and avoid large vessels when performing direct aspiration biopsy with the cutter. We also raise the intraocular pressure and introduce the cutter at a low cut rate to help prevent hemorrhage. Complications associated with these approaches include cataract, retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, choroidal hemorrhage, proliferative vitreoretinopathy and endophthalmitis.5

Our biopsy experience

Resembling our experiences, other cases of false-negative vitreous studies have been reported, with definitive diagnoses later confirmed using retinal/RPE biopsies.1,2,4,9 In our recently completed single-center retrospective study, 51 patients had diagnostic vitrectomies suspicious for vitreoretinal lymphoma, 39 of which were positive (76.5 percent). Of these, 29 were vitreous-positive (three of which were retinal and/or subretinal biopsy [RSRB]-positive). The remaining 10 positive biopsies were noted to be vitreous negative but RSRB positive. We performed 14 RSRB, 13 of which were positive for vitreoretinal lymphoma (92 percent).

Most interestingly, 21 patients had retinal, subretinal and/or sub-RPE lesions on their initial visit, 13 of whom (62 percent) had a negative vitreous biopsy. This suggests that if patients present with clear lesions, the vitreous specimen may have a lower cytopathological yield.

The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis was 7.45 months among all patients. However, patients who tested positive only on RSRB tended to present at a later stage than patients with positive vitreous biopsies. Among RSRB-positive but vitreous-negative patients, the time to diagnosis was 8.56 months. For patients with positive vitreous biopsy, the average time to onset was 5.07 months (p=0.002).

A more chronic disease course?

|

We found no differences in vitreous haze scores between the two groups. We hypothesize that by the time a lesion develops, the disease course is more chronic. Given the fragility and necrosis of vitreous lymphocyte cells, the vitreous yield may decline with time. We used two different RSRBs techniques in our study: cutting/aspiration with a vitrector; or bimanual dissection with scissors and forceps. We performed 10 RSRBs with a cutting/aspiration technique with the vitreous cutter and four with a dissection technique with retinal scissors.

Importantly, only two postoperative retinal detachments occurred in the series, both in RSRB patients utilizing the cutting/aspiration technique. We used follow-up PPV with gas-tamponade in both for reattachment.

How we choose a biopsy technique

With these findings in mind, we highly consider RSRB for suspicious cases at time of primary diagnostic vitrectomy to expedite diagnosis and treatment.9

Biopsy methods may differ depending on provider preference and experience. We prefer PPV due to our comfort with the procedure and our preference for a definitive diagnosis at the time of initial surgery.

Ocular imaging is also invaluable as a supplementary tool. Preoperative and/or intraoperative OCT, a key portion of our surgical management, aids our decision to perform direct aspirate through a lesion vs. a dissection.1 We favor subretinal aspirate (Figure 1C) when the pathology is confined to the subretinal and sub-RPE space, whereas we opt for a full-thickness retinal and RPE biopsy in cases with full-thickness retinal involvement without subretinal involvement (Figures 2B, C).

In terms of the biopsies themselves, we prefer complete vitrectomies in place of limited core vitrectomies to reduce the likelihood of false-negative results. This is because inflammatory and lymphoma cells, believed to be predominantly in the cortical vitreous, have a diminished chance to be sampled with only a core biopsy.5 Necrotic cells may predominate the center of a lesion. Lesion margins are more likely to harbor the pathologic process.5 We prefer to avoid oral or periocular steroids for at least two weeks preprocedure to limit risk of cellular necrosis before the biopsy Finally, we can’t emphasize this enough: Proper coordination with cytopathology is a must.6

Bottom line

Retina specialists have several biopsy options for the diagnosis of atypical uveitis. Biopsy methods may differ depending on provider preference and experience. Consider RSRB during initial surgery for highly suspicious cases to expedite the diagnosis and treatment.9 In the future, PCR or metagenomic sampling of aqueous or vitreous fluid may also play a key role in the diagnosis of vitreoretinal lymphoma.10,11 RS

REFERENCES

1. Lim LL, Suhler EB, Rosenbaum JT, Wilson DJ. The role of choroidal and retinal biopsies in the diagnosis and management of atypical presentations of uveitis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2005;103:84-91; discussion 91-92.

2. Johnston RL, Tufail A, Lightman S, et al. Retinal and choroidal biopsies are helpful in unclear uveitis of suspected infectious or malignant origin. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:522-528.

3. Tang LJ, Gu CL, Zhang P. Intraocular lymphoma. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10:1301-1307.

4. Mastropasqua R, Thaung C, Pavesio C, et al. The role of chorioretinal biopsy in the diagnosis of intraocular lymphoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:1127-1132.

5. Mastropasqua R, Di Carlo E, Sorrentino C, Mariotti C, da Cruz L. Intraocular biopsy and immunomolecular pathology for "unmasking" intraocular inflammatory diseases. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1733.

6. Singh AD, Biscotti CV. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of ophthalmic tumors. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2012;26:117-123.

7. Mashayekhi A, Mazloumi M, Shields CL, Shields JA. Choroidal neovascular membrane after fine-needle aspiration biopsy of vitreoretinal lymphoma. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2022;16:25-28.

8. Ebert JJ, Di Nicola M, Williams BK Jr. Operative complications of posterior uveal melanoma surgery. Inter Ophthalmol Clin. 2022;62:15-33.

9. Srivastava SK, Mammo DA, Hamdan A. Vitreoretinal biopsy techniques and the role for retinal biopsy in vitreoretinal lymphoma: a single-institution experience. Paper presented at the American Society of Retina Specialists 40th annual scientific meeting; Chicago, IL; July 14, 2022.

10. Hakan D, Rao RC, Elner VM, et al. Aqueous humor–derived MYD88 L265P mutation analysis in vitreoretinal lymphoma: A potential less invasive method for diagnosis and treatment response assessment. Ophthalmol Retina. 2023;7:189-195.

11. Gonzales J, Doan T, Shantha JG, et al. Metagenomic deep sequencing of aqueous fluid detects intraocular lymphomas. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:6-8.