Take-home points

|

|

|

Bios DISCLOSURE: Dr. Chang is a paid consultant and speaker for EyePoint Pharmaceuticals. |

Adoption of immunotherapy to treat metastatic melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer and several other malignancies has contributed to the increased incidence of immunotherapy-driven noninfectious uveitis (NIU). By understanding the biological mechanisms underpinning this phenomenon and reviewing treatment options, retina specialists can be better prepared to manage these cases upon referral from an oncologist.

After exploring these topics, I’ll present a case that illustrates the value of localized corticosteroid therapy—in this instance, use of the fluocinolone acetonide implant 0.18 mg (Yutiq, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals)—to treat NIU secondary to systemic immunotherapy for cancer.

Immunotherapy: Side effects and ocular manifestations

Immunotherapy is an effective means of assisting the immune system’s ability to detect and destroy cancer cells, and it has been used in combination with other therapies to treat metastatic melanoma.1,2 The underlying biologic mechanisms that boost immune response result in T-cell activation, increased production of cytokines, and enhanced T-cell-mediated immune responses.3,4

In Taiwan, Chia-Jui Chang, MD, and colleagues have recorded several dermatological, gastrointestinal, nephrological, neurological, pancreatic, endocrine, hepatic and ocular adverse events that were reported following immunotherapy administration, including dry eyes and NIU.5 The root cause for uveitic manifestations may be the melanocytes present in the uveal tract.

In my experience, patients present with uveitic symptoms after two to three rounds of immunotherapy. Patients with NIU secondary to immunotherapy are typically referred to me for examination by an oncologist.

Patients with anterior NIU typically report photophobia, redness and blurry vision. Those with posterior NIU typically have blurry vision, floaters and sometimes scotomas. Patients with panuveitis can have any or all of these signs and symptoms.

Therapeutic options

Several treatment options exist for patients with NIU who are otherwise healthy, including local and systemic corticosteroid therapy, as well as systemic immunosuppression. Each of these approaches has advantages and disadvantages.

Local steroid therapy in the form of drops, periocular and intravitreal injections may be appropriate for some patients with acute flare. In patients with chronic NIU, steroid-eluting implants that release fluocinolone acetonide or dexamethasone may be more appropriate. Still, long-term ocular exposure to steroids may be undesirable because of the increased risk of intraocular pressure elevation or, in phakic patients, cataract progression.

Long-term systemic steroid therapy may lead to any number of complications. These can include weight gain and decreased bone density, although long-term systemic steroids may mitigate the risk of cataract or glaucoma that can come with localized therapy. Systemic immunosuppression may be an effective approach in otherwise healthy patients. However, immunosuppression among patients who are undergoing cancer immunotherapy is counterproductive, so it’s not advisable.

Case report: NIU in a woman with metastatic cutaneous melanoma

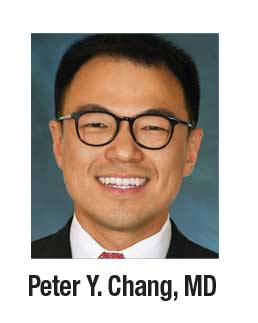

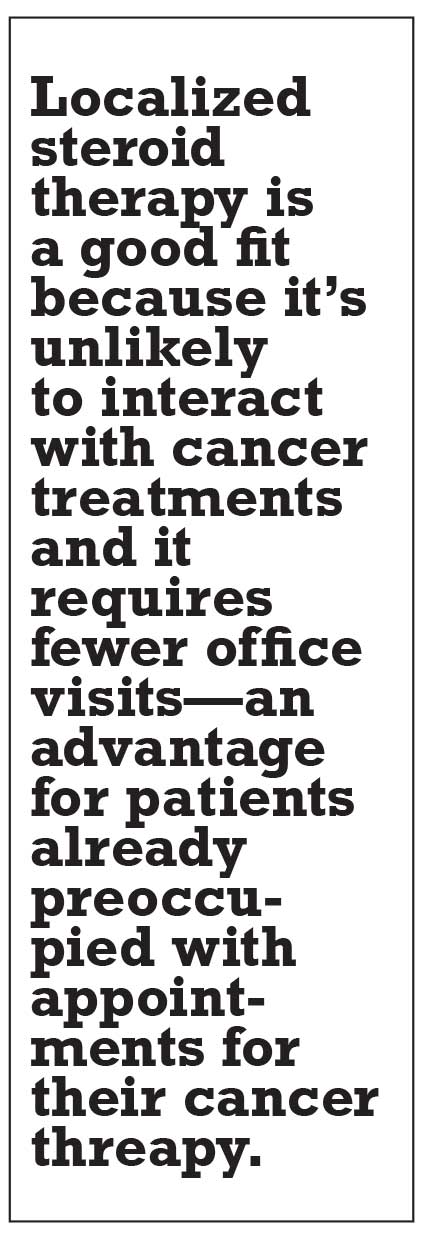

A 46-year-old woman with metastatic cutaneous melanoma presented with floaters and blurry vision six weeks after starting intravenous ipilimumab and nivolumab (the combination therapy was administered every three weeks). On exam, visual acuity was 20/40 OU, and intraocular pressure was within normal limits. There were trace anterior chamber cells and no lenticular changes. Fundoscopic exam revealed 1+ vitreous cells and blurry optic disc margin OU with subtle chorioretinal folds in the peripapillary region that also involved the nasal macula. Optical coherence tomography showed trace subretinal fluid in the peripapillary region OU (Figure 1), and fluorescein angiography imaging revealed optic nerve leakage with punctate hyperfluorescence consistent with leakage around the nerve and the macula (Figure 2). The patient denied headaches, tinnitus, or other signs that would suggest Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Given that her symptoms presented close to the initiation of ipilimumab therapy, a diagnosis of immunotherapy-associated posterior uveitis was made. The patient initially received bilateral intravitreal dexamethasone implant 0.7 mg (Ozurdex, Allergan/AbbVie) injections, but her uveitis relapsed after three months as she continued to receive nivolumab.

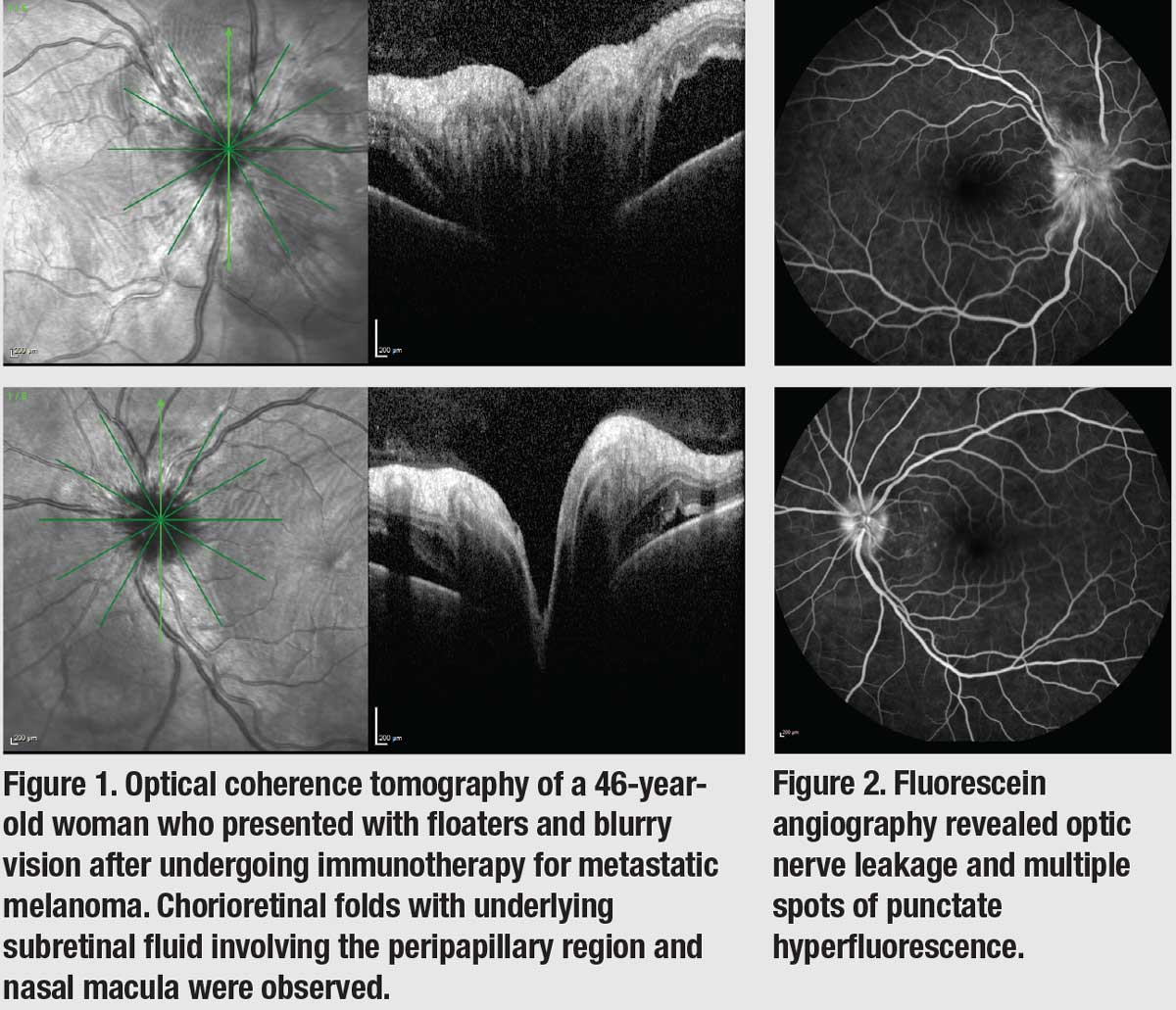

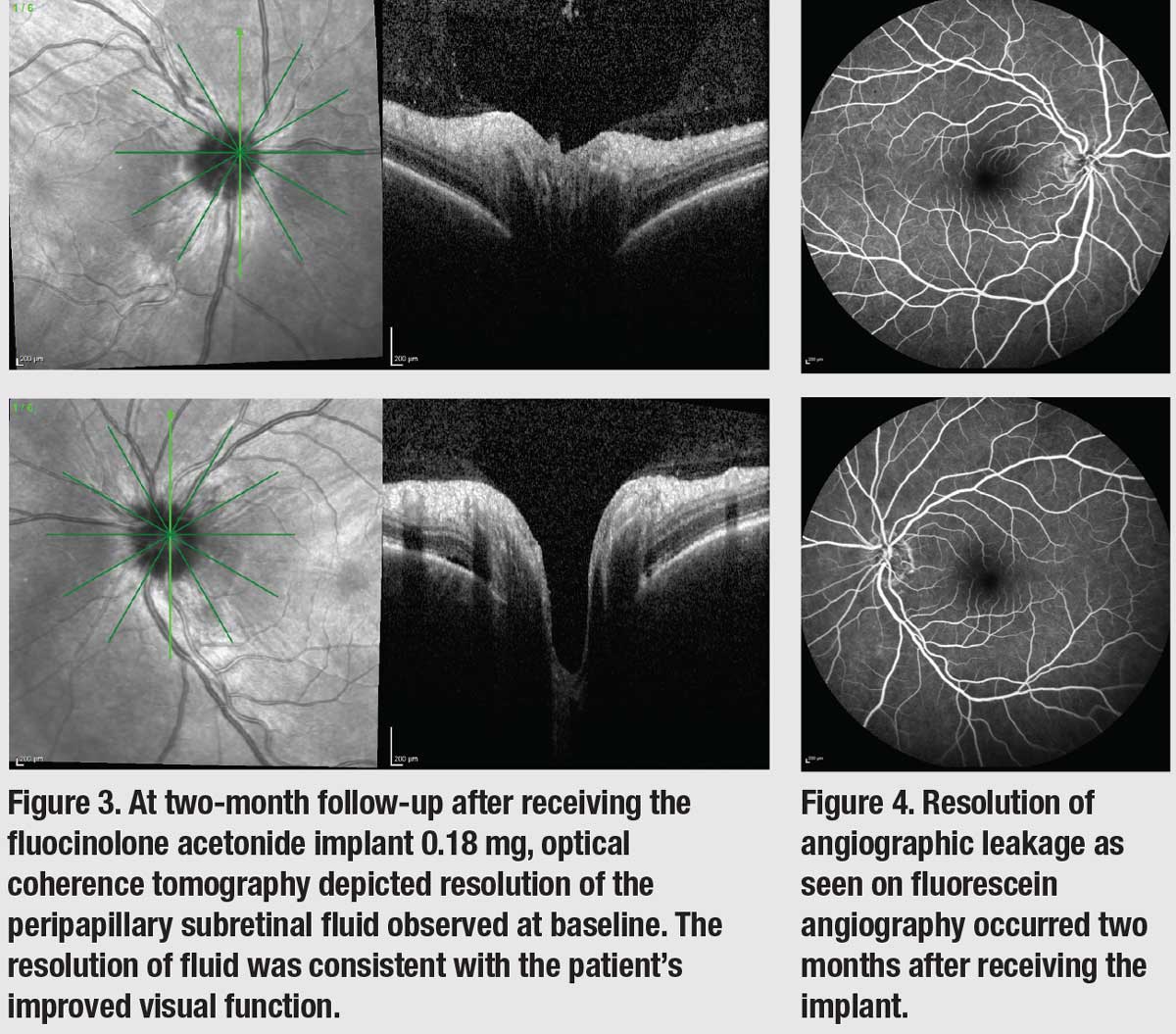

Because the immunotherapy was effective in halting her metastatic disease, a decision was made to proceed with fluocinolone acetonide implant 0.18 mg (Yutiq, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals) therapy in both eyes for long-term control of her uveitis. Two months after the initiation of the implant, OCT imaging showed resolution of the peripapillary subretinal fluid (Figure 3), and FA imaging showed that the angiographic leakages had resolved completely (Figure 4). Visual acuity returned to 20/20 OU. One year after treatment, the patient hasn’t developed IOP elevation, although a small posterior subcapsular cataract has formed, minimally affecting her vision. Her metastatic melanoma remains stable with nivolumab. |

Localized steroid therapy

Clinicians encountering patients with NIU secondary to immunotherapy must determine how to treat a patient’s ocular condition without significantly affecting their cancer treatments. Typically, when a patient fitting this profile presents to the clinic, I find that localized steroid therapy is a good fit because it keeps any treatment localized to the eye and, therefore, unlikely to interact with their cancer treatment. It also requires fewer office visits—an advantage for patients who are already preoccupied with appointments for cancer therapy.

I begin treatment with a course of steroid drops. This is often adequate, particularly in cases of anterior NIU. But in cases of posterior NIU or panuveitis, drops may not have enough ocular penetration. For these patients, intravitreal injections, periocular injections or sustained-release steroid implants may be effective.

|

In my practice, use of the sustained-release steroid fluocinolone acetonide implant 0.18 mg, which is indicated for chronic NIU affecting the posterior segment,6 has been effective at treating patients undergoing immunotherapy who present with NIU in the posterior segment. The array of treatment options for elevated IOP alleviates concerns about the increased risk of glaucoma. I’m less concerned about premature cataract development in patients with NIU secondary to immunotherapy, because they’re typically old enough that they’re nearing the age for cataract surgery. The fluocinolone acetonide implant 0.18 mg is injected in an office setting and is designed to elute the active agent for 36 months.

Two other sustained-release steroid options exist for these patients: intravitreal dexamethasone implant 0.7 mg (Ozurdex, Allergan/AbbVie); and fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant 0.59 mg (Retisert, Bausch + Lomb).

I’m reluctant to use the intravitreal dexamethasone implant 0.7 mg in these patients because it has a shorter duration of action (i.e., rarely more than three to four months in NIU). The fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant 0.59 mg is more invasive and costly, and it has been associated with faster cataract progression and higher incidence of steroid-induced glaucoma. I use it only in the most refractory cases.

My experience with the fluocinolone acetonide implant 0.18 mg in patients who have NIU as a consequence of cancer immunotherapy has been positive, as the case above illustrates.

Bottom line

Patients with metastatic melanoma or other advanced malignancies who are undergoing immunotherapy may be referred to your clinic if they report ocular side effects to their oncologist. In cases of NIU affecting the posterior segment, I advise considering localized steroid therapy because it will stay contained to the eye and won’t interfere with the patient’s systemic cancer treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Sharma P, Allison JP. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: Toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell. 2015;161:205-214.

2. Kim T, Amaria RN, Spencer C, et al. Combining targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Cancer Biol Med. 2014;11:237-246.

3. Peggs KS, Quezada SA, Korman AJ, Allison JP. Principles and use of anti-CTLA4 antibody in human cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:206-213.

4. Tarhini A, Lo E, Minor DR. Releasing the brake on the immune system: Ipilimumab in melanoma and other tumors. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2010;25:601-613.

5. Chang C, Chen S, Hwang D, Liu CJ. Bilateral anterior uveitis after immunotherapy for malignant melanoma. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2018;8:173-175.

6. Yutiq [package insert]. Watertown, MA; EyePoint Pharmaceuticals. 2018.

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge. Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.