Take-home Points

|

|

|

Bio Dr. Garg is a professor of ophthalmology and co-director of retina research at The Retina Service of Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, and is a partner with Mid Atlantic Retina. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Garg has no relevant financial relationships to disclose. |

I’m not one prone to Schadenfreude, but when a 2012 study found that 46 percent of ophthalmologists had neck pain, 26 percent had back pain, and 17 percent had wrist or hand pain, I was relieved—not because others were suffering, but because I wasn’t alone.1 I started having back pain during my second year of residency doing strabismus surgery, of all things. Since then, keeping my neck, back, wrists and now shoulders pain-free has been an ongoing endeavor.

Ophthalmologists have a higher risk of occupational injury than other physicians. One early study found that ophthalmologists reporting neck symptoms tended to be younger and were more likely to be women, tended to be in practice for fewer years, and reported higher stress levels.2 Interestingly, the authors found that musculoskeletal issues seemed to be independent of the number of patients or surgeries performed. However, other studies demonstrated that repetitive work injuries seemed to increase along with the workload.3

The main reasons for our work issues are poor posture, repetitive motions and the fact that we repeatedly maintain really awkward positions such as using the headlamp or hunching over the slit lamp.4-6 In this article, I’ll explain the causes of our problems with occupation-related injury, and then share a few solutions.

The problems

Our workflow isn’t designed for the long-term health of our own bodies, as these four elements of our routine illustrate:

|

| Figure 1. The computer system is at a 90-degree angle to the patient, which requires quite a twist to see the patient. Sitting properly also reduces the need to hunch over. (Photos by Alexa Bednar) |

• Exam room setup. Our computers are set up against one wall with the patient’s chair 90 degrees away (Figure 1). After I walk into the room, I stand in front of the patient and turn my head 90 degrees to look at the screen—clearly not a recipe for spinal happiness. Rather than sitting properly, I tend to crouch over and start typing while sitting awkwardly.

• The slit lamp. While the slit lamp is an amazing piece of design and engineering, it induces bad posture. Due to the fixed position of the oculars, many of us end up hunching forward. Holding the condensing lens with our arms outstretched puts stress on our shoulders and upper back, and grasping the lens causes wrist and hand problems. Additionally, the slit lamp tables are often unnecessarily large, forcing us to sit back farther from the slit lamp. Those of us with larger torsos and/or abdomens also have to sit farther back, additionally causing dorsiflexion of the neck.

• Indirect ophthalmoscopy. Here, we end up standing in awkward positions and twisting our neck from side to side, all of which sets us up for musculoskeletal issues in the future.

• The operating room. Mostly we use whatever chairs, OR tables and microscopes are available. I use a Machemer stool, which is really comfortable; however, the wide circular base sometimes hits the foot pedals, which I then have to push farther from me. The oculars may or may not tilt enough to enable us to sit upright. When I’m operating with our fellows, the poorly positioned assistant scope forces me to sit side-saddle because there isn’t enough room for my legs under the table.

The solutions

There are a number of things we can do to help reduce injury. Here are some ideas:

|

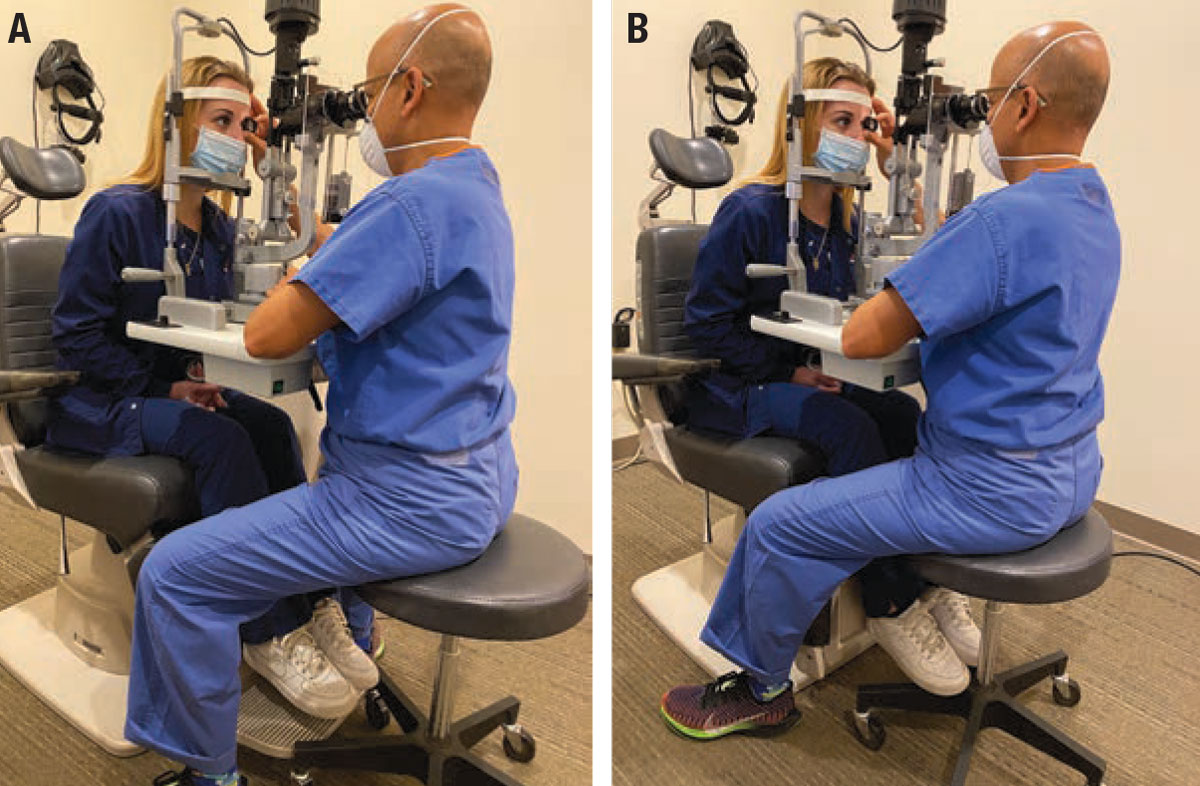

| Figure 2. A) When the footrest is down, the rolling stool can move forward, causing you to lean forward and dorsiflex your neck. B) Lifting the footrest lets you position the stool closer to the patient so you can sit more upright. |

• In the clinic. The examination stool can hit the footrest, which forces us to sit farther back, requiring us to lean forward to get to the oculars and then tilt back our heads in order to look straight on. Doing something as simple as lifting up the footrest allows me to slide my chair closer to the patient, enabling me to sit more upright (Figure 2).

• Slit lamp table. It’s often positioned unnecessarily deep, forcing us to sit farther away from the patient, functionally creating a posture similar to what was happening when the footrest was down. Getting a narrower slit lamp table is possible, but often equipment manufacturers and suppliers aren’t aware or aren’t equipped to help us with this. Physicians that have done this usually hire outside contractors to make a new table. It doesn’t take much time, and it’s not expensive, but it does require effort to find someone to do the job.

• Condensing lens. Holding the condensing lens with your hand neutral is generally the best position; flexing or extending the wrists causes unnecessary strain. An elbow rest made of foam can also relieve some shoulder strain.

|

|

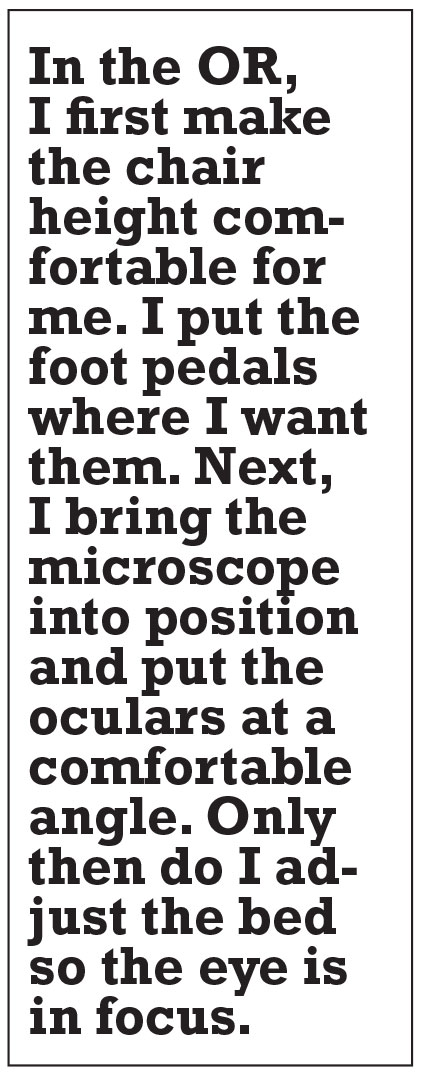

Figure 3. What not to do: Tilting the oculars down requires you to look up, leading to neck dorsiflexion. Adjusting the oculars so you look straight ahead or down allows the neck to be in a more neutral position. (Photo by Kathryn Lynn) |

In the OR

I stress the importance of positioning to my fellows. Often I see the patient wheeled into the room, basically left where they are on the bed. The fellow drops the microscope in, sort of adjusts the chair, and then hunches over or stretches to reach the oculars. This might be acceptable for a few cases when you’re 30, but it’s definitely not a recipe for long-term well-being. A better approach is to remake the OR environment so it’s centered around the surgeon. Here are some steps I take to accomplish that:

• Chair height and microscope positioning. Essentially, I first make the chair height comfortable for me. I put the foot pedals where I want them. Next, I bring the microscope into position and put the oculars at a comfortable angle, ideally looking straight ahead or slightly down (Figure 3). Only then do I adjust the bed so the eye is in focus. By doing this, I don’t force my body to adapt to the machinery; instead, I adapt the machinery to my body.

• Patient positioning. I also ensure the patient is at the very top edge of the bed. A lot of times I see my fellows put the top of the patient’s hair at the top of the bed, but if someone has a beehive that can

|

still position their eye two feet away. Also, I’ll see people level the top of the patient’s head to the cushion, but the cushion itself is also halfway in the middle of the bed. I’m very particular about making sure the patient’s head is at or slightly over the top of the metal portion of the stretcher. This enables me to put the patient’s head essentially adjacent to my abdomen, allowing me to sit upright.

Some surgeons have suggested that a heads-up display may be more ergonomic, as it frees the surgeon from the confines of the microscope. I haven’t found the current iterations of the heads-up display systems I’ve used to be advantageous in this regard.7,8

• Proper wrist rest use. When we routinely used 20-gauge vitrectomy or non-valved cannulas, there was a tremendous loss of fluid. Unless you wanted to have a wet leg, the trough needed to be supported by the wrist rest. With valved cannulas, there’s little fluid loss during our cases, so this use of the wrist rest is less important.

Some surgeons use the wrist rest as a way to help stabilize their hands and take some of the load off their arms. However, most of my trainees use the wrist rest as a decoration. The problem with using a wrist rest unnecessarily is that it also separates you from the patient’s head by 3 to 4 inches. Similar to what we were encountering with improper head positioning, the wrist rest forces you to sit back farther from the patient, requiring most of us to then tilt slightly forward, exacerbating neck or back pain.

| Ergonomics of the body and mind: Yoga and other remedies

Yoga has also helped increase my body and mind awareness. This helps me pay attention to my body alignment, and has helped me maintain a greater degree of awareness, not only of what I’m doing in the eye, but also of all that’s happening in the OR as well. I’ve occasionally been in circumstances where things were going in an unintended direction. I’m able to be aware of when my anxiety increases, and I have strategies to help quiet my mind and body to handle the situation in front of me. There is a specific form of yoga called Iyengar Yoga. This is definitely not the Lululemon set who can put their big toe in their ear! An essential part of an Iyengar teacher’s education is helping people maintain different postures as their body allows, using props when necessary so the student can get the benefit of a posture while reducing any risk of injury. The attention to form and process, I think, is well suited to the ophthalmology mindset. Pilates can also be a great exercise. Much of what we do involves good upright posture which needs good core strength—Pilates’ forte. Other forms of physical therapy, massage and chiropractic work can also be of benefit. –S.G. |

• Positioning the arms. It’s important to keep your arms hanging loosely at your side. I’ve seen people who operate with their arms out to the side and their elbows pointed to the corners of the room sort of like they’re getting ready to do the chicken dance at a high school prom. The only other reason to do this is because your underarms are getting all sweaty. If that’s the case, consider investing in a better deodorant.

Advocacy

As a profession, we need to better engage with industry to improve the ergonomics of our work environment. Awareness and physical conditioning can only do so much. A few years ago the American Academy of Ophthalmology had a task force on ergonomics. This group identified a number of strategies, including extended oculars, improved slit lamp ergonomics and ergonomically friendly computer workstation changes. Many of these changes aren’t things that we can do by ourselves. We need to push our societies and equipment manufacturers to address this issue now so that we and our other colleagues can reap the benefits for years to come. RS

Recently, Dr. Garg, along with Samuel Masket, MD, Alison Early, MD, and Luisa DiLorenzo, MD, hosted an American Academy of Ophthalmology webinar on ergonomics. It’s available at https://aao-org.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_M96tsbCiQL-qC3iKFX7Ipg.

REFERENCES

1. Kitzmann AS, Fethke NB, Baratz KH, Zimmerman MB, Hackbarth DJ, Gehrs KM. A survey study of musculoskeletal disorders among eye care physicians compared with family medicine physicians. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:213-220.

2. Dhimitri KC, McGwin G Jr, McNeal SF, et al. Symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmologists. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:179-181.

3. Schechet SA, DeVience E, DeVience S, Shukla S, Kaleem M. Survey of musculoskeletal disorders among US ophthalmologists. Digit J Ophthalmol. 2020;26:36-45.

4. Venkatesh R, Kumar S. Back pain in ophthalmology: National survey of Indian ophthalmologists. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65:678-682.

5. Marx JL. Ergonomics: Back to the future. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:211-212.

6. Betsch D, Gjerde H, Lewis D, Tresidder R, Gupta RR. Ergonomics in the operating room: It doesn't hurt to think about it, but it may hurt not to! Can J Ophthalmol. 2020;55(3 Suppl 1):17-21.

7. Bin Helayel H, Al-Mazidi S, AlAkeely A. Can the three-dimensional heads-up display improve ergonomics, surgical performance, and ophthalmology training compared to conventional microscopy? Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:679-686.

8. Weinstock RJ, Ainslie-Garcia MH, Ferko NC, et al. Comparative assessment of ergonomic experience with heads-up display and conventional surgical microscope in the operating room. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:347-356.