Take-home Points

|

|

|

Bios Dr. Grewal is a vitreoretinal and uveitis specialist at Duke Health in Durham, North Carolina. DISCLOSURE: Dr. Grewal disclosed acting as a consultant to Allergan/AbbVie, Clearside Biomedical, DORC and EyePoint Pharmaceuticals. |

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted care patterns and led to potential disease management changes across many therapeutic areas. Early on, ophthalmology was one of the most affected specialties in medicine, with some practices severely curtailed for about two months, doing only the most urgent procedures. For example, Italian researchers reported an 86-percent reduction in outpatient treatment for posterior uveitis in spring 2020 compared to the prior year.1

Even now, although clinics have reopened and vaccinations are ramping up, challenges still exist in getting our patients to the clinic, and widespread vaccination is still a few months away. Younger patients may have children at home and find it more difficult than usual to get away. Older patients who live in assisted-living or a skilled-nursing facility may still have strict requirements for leaving or returning to their community. Others simply remain very fearful. Some have opted to delay care to avoid leaving home. Unfortunately, these delays have led to some cases of disease progression.

Even as more people get vaccinated, some of these precautions should stay in place because it’s going to take months before we reach herd immunity and our offices are up and running at full capacity.

Diagnostic protocols

|

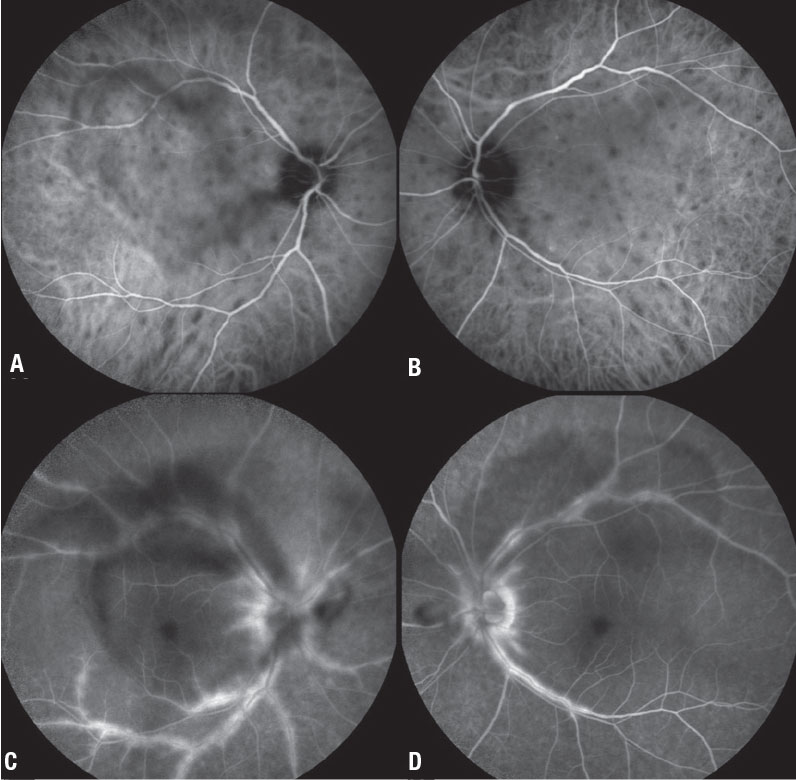

| Figure 1. Indocyanine green angiography (A, B) shows multiple round-to-oval hypocyanescent choroidal lesions throughout the posterior pole in a 40-year-old woman with birdshot chorioretinitis. Disease activity persisted despite adalimumab 40 mg (Humira, AbbVie) monotherapy q2w. Fluorescein angiography (C, D) shows significant posterior pole perivascular leakage with visible vitreous opacities consistent with vitreous inflammation. After offering her the options of a second immunosuppressive agent or local therapy, she opted for the latter. |

For all of our known or potential uveitis patients entering the clinic, awareness of COVID-19 status is important. Justine Smith, MBBS, PhD, and Timothy Y.Y. Lai, MD, in Australia recommended as of last May avoiding aerosol-generating diagnostic procedures that pose a high risk of viral transmission.3 For example, they suggest that diagnostic bronchoscopy is unnecessary if the presentation is otherwise consistent with ocular sarcoidosis. Lower-risk diagnostic procedures can be planned in collaboration with internist colleagues.

Vitrectomy is no longer contraindicated in COVID-negative patients. In COVID-

positive patients, full personal protective equipment should be worn, and a COVID-specific operating room used for essential diagnostic or surgical procedures.2

In the clinic, we follow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, including phone prescreening, limiting waiting room times, social distancing, mandatory masks, slit lamp shields,

enhanced cleaning of the room and equipment between patients, and universal COVID testing for surgical patients. In some cases, we’ve been able to switch to telemedicine visits, but that can be quite challenging for retinal conditions, including posterior uveitis.

Virus risk and uveitis patients

It’s important to note that noninfectious posterior uveitis patients are predisposed to autoimmune issues and may be at higher risk than the general population of suffering a more severe course of the virus.3,4 It’s possible that an overactive immune system could be prone to the so-called cytokine storm that’s been associated with severe cases of COVID-19. We know that interleukin-6 (IL-6) is upregulated in COVID-19, as well as in some uveitic conditions.

Additionally, management of posterior noninfectious uveitis often involves suppression of the immune system with steroids or immunomodulatory agents. Pre-pandemic, clinicians advised uveitis patients on systemic treatments to be careful with hand-washing and avoid exposure to sick people. Precautions are even more important now.3

Discussion of treatment options

|

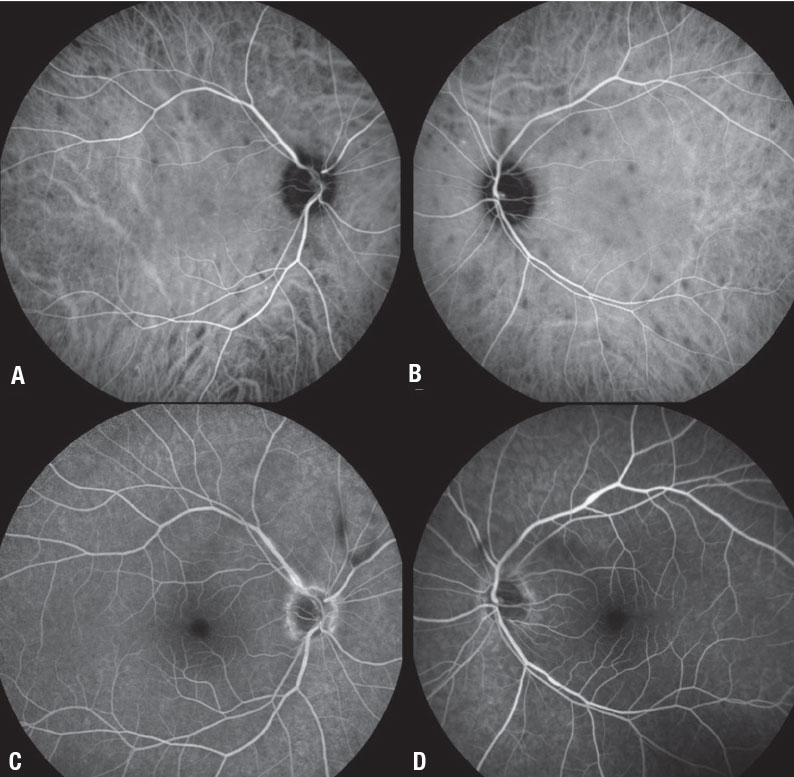

| Figure 2. Three months after we added the fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant 0.18 mg in both eyes of the patient in Figure 1, fluorescein angiography demonstrates significant reduction in the size and number of the hypocyanescent lesions (A, B) and near complete resolution of perivascular leakage, along with much improved vitreous inflammation (C, D). |

Increasingly, a consensus has emerged that posterior uveitis patients well-managed on systemic immunosuppressive therapy should continue their current management while taking all recommended precautions.2,3,5,6 However, we must also take the patient’s lifestyle and preferences into consideration.

Even as vaccines roll out, the care of patients on immunosuppression therapy remains a concern. The American College of Rheumatology has issued guidelines for managing patients on immunosuppression receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.7 Medications such as methotrexate should be withheld for one week after each vaccine dose, whereas others, such as mycophenolate, azathioprine or steroids, don’t require any modification.

If the patient is apprehensive about immunosuppression, a discussion on alternatives is warranted. In most cases, the risk of a flareup with discontinuation or weaning off the systemic medication, combined with the additional office visits associated with a change in management, may counterbalance the risk of contracting COVID-19. However, for some patients who have already contracted pneumonia or another infection, or for those at very high risk of exposure (for example, health-care workers or those with jobs that require high levels of public contact), we may alter the risk assessment.

In general, we need to weigh not only the patient’s current therapy and uveitis severity, but also their ocular and systemic comorbidities, age, lens status and personal preferences. Patients with underlying conditions such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis or sarcoidosis will likely be best served by maintaining immunosuppression, because it treats their systemic and ocular problems.

Who merits a change in approach

|

In my practice, there are two distinct groups of patients for whom I consider a change in approach to reduce or avoid immunosuppression. The first is the newly diagnosed patient or one who isn’t completely controlled on their current immunosuppressive therapy and for whom I would normally be adding an additional immunosuppressive agent. In these patients, supplementation with local steroid therapy may help delay or avoid additional immunosuppression.3,5,6 Figures 1 and 2 (page 25) illustrate such an example.

The second group is those who require multiple immunosuppressive agents only for the eye and are concerned about the amount of immunosuppression. I discuss with them the possibility of reducing the burden of immunosuppression. Perhaps we take away one of the immunosuppressive agents and, if ocular comorbidities allow, supplement with a local steroid therapy.

Local steroid therapy will cause a cataract, which is a concern in a young patient who still has accommodation, especially if both eyes are involved and would require bilateral injections.

In older patients in the later stages of presbyopia, cataract development is less of a concern. We also have to consider the risk of a steroid response with an intraocular pressure elevation, especially if the patient already has glaucoma.

Sustained-release options

Once it has been determined that the patient has chronic noninfectious posterior uveitis, it’s important to explain that the goal of treatment is sustained control of inflammation. We know that fluctuations in inflammatory activity can produce a yo-yo effect in which after the uveitis flares up and subsides, vision doesn’t necessarily return to baseline. With each flare-up, the patient may lose some visual quality or visual function, with the potential for significant cumulative decline over time. Sustained-release (SR) local steroid therapy offers the potential to achieve a steady state in uveitis control.

SR ophthalmic drug delivery has been an important focus over the past several years because there’s such a high need— not only in uveitis, but in conditions such as macular degeneration, retinal vein occlusion, glaucoma and diabetic macular edema.

The first SR steroid technology in ophthalmology was the fluocinolone-releasing Retisert (Bausch + Lomb). It has the advantage of a long duration of effect (three years), but it must be implanted surgically in the operating room, with a large incision and sutures. Additionally, while Retisert is very powerful at reducing inflammation, it causes cataract and has a high rate of IOP elevation.

Next-generation platforms

|

As SR technology has continued to advance, the drug reservoirs have become much smaller and can be injected in the office. The first such implant was Ozurdex (Allergan/AbbVie), a rice-grain-sized, bioerodible pellet that releases dexamethasone for three to six months.

More recently, we have a new SR technology, Yutiq (EyePoint Pharmaceuticals), that’s approved to treat posterior noninfectious uveitis. It combines the durability of Retisert and the convenience of an in-office procedure like Ozurdex, with less IOP elevation than Retisert.8,9

Yutiq has about one third of the fluocinolone of Retisert (0.18 mg vs. 0.59 mg), and the slow release provides a sustained anti-inflammatory effect over three years, with much lower risk of IOP rise and cataract formation due to the lower dose.8,9 This profile makes it a good potential choice for those uveitis patients who would like to delay or reduce immunosuppression during the pandemic.

Precautionary pre-insertion steps

In a patient who has never received a local steroid injection, I prefer to first evaluate their response to a single short-acting steroid injection, in terms of both efficacy and tolerability, before proceeding with an SR insert. In addition to evaluating for an increase in IOP, it also helps to confirm that the patient is responding well to the steroid. The injection provides a bolus of steroid that can rapidly reduce the macular edema, if present. This can be followed with an SR implant to keep the edema and uveitis controlled over the long term.

It’s important to recognize that local therapy isn’t a good choice for some patients, including those with very severe, sight-threatening inflammation along with systemic inflammation that requires immediate control; pediatric patients; those with uncontrollable IOP elevation; and patients with severe glaucoma who can’t tolerate any pressure increase.

Bottom line

In most patients, the risk of uveitis disease progression with no treatment or undertreatment is much greater than the risk of contracting COVID-19. It’s our role to help patients understand their relative risks and to responsibly weigh all the factors that go into decision-making for the management of uveitis, including comorbidities and patient preferences.

Even as the pandemic subsides, it may make sense to delay or reduce the burden of systemic immunosuppression for some patients. In these cases, local therapy with SR steroids can be a very effective tool. Of course. no treatment is perfectly safe and effective. For this reason, we must always be prepared to make adjustments and reassess the risks for our patients. RS

REFERENCES

1. Borrelli E, Grosso D, Vella G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on outpatient visits and intravitreal treatments in a referral retina unit: Let’s be ready for a plausible “rebound effect.” Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258:2655-2660.

2. Smith JR, Lai TYY. Managing uveitis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:e65-67.

3. Agarwal R, Testi I, Lee CS, et al. Evolving consensus for immunomodulatory therapy in non-infectious uveitis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Ophthalmol. Published online June 25, 2020. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316776.

4. International Uveitis Study Group, Foster Ocular Inflammation Society and International Ocular Inflammation Society. Evolving consensus experience of the IUSG-IOIS-FOIS with uveitis in the time of COVID-19 infection. April 3, 2020. https://www.iusg.net/uploads/images/IUSG%20Library/v004-consensus-experience-document.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2020.

5. Hung JCH, Li KKW. Implications of COVID-19 for uveitis patients: Perspectives from Hong Kong. Eye 2020;34:1163-1164.

7. Agarwal AK, Sudharshan S, Mahendradas P, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on uveitis patients receiving immunomodulatory and biological therapies (COPE Study). Br J Ophthalmol. Published online October 3, 2020. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317417.

7. COVID-19 vaccine glinical guidance summary for patients with rheumatic and muscoloskeletal diseases. American College of Rheumatology. https://www.rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/COVID-19-Vaccine-Clinical-Guidance-Rheumatic-Diseases-Summary.pdf. Updated February 8, 2021.

8. Jaffe GJ, Pavesio CE, Study investigators. Effect of a fluocinolone acetonide insert on recurrence rates in noninfectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis: Three-year results. Ophthalmology 2020;127:1395-1404.

9. Eyepoint Pharmaceuticals. Full prescribing information. Yutiq.com. https://eyepointpharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/YUTIQ-USPI-20181120.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2020.