Take-home Points

|

|

|

Bios Dr. Russell is chief resident and director of ocular trauma at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Dr. Smiddy and Dr. Flynn are professors of ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. DISCLOSURES: The authors have no relevant relationships to disclose. |

Retinal breaks are full-thickness discontinuities in the neurosensory retina. Asymptomatic retinal breaks have a very low risk of retinal detachment.1 Retinal breaks associated with symptoms of floaters and/or photopsias occurring in the setting of acute posterior vitreous detachment are more likely to cause rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

Here, we answer five commonly encountered clinical questions about the course of PVD and symptomatic retinal breaks that should be considered in formulating management decisions.

1. How often is symptomatic PVD associated with a retinal break?

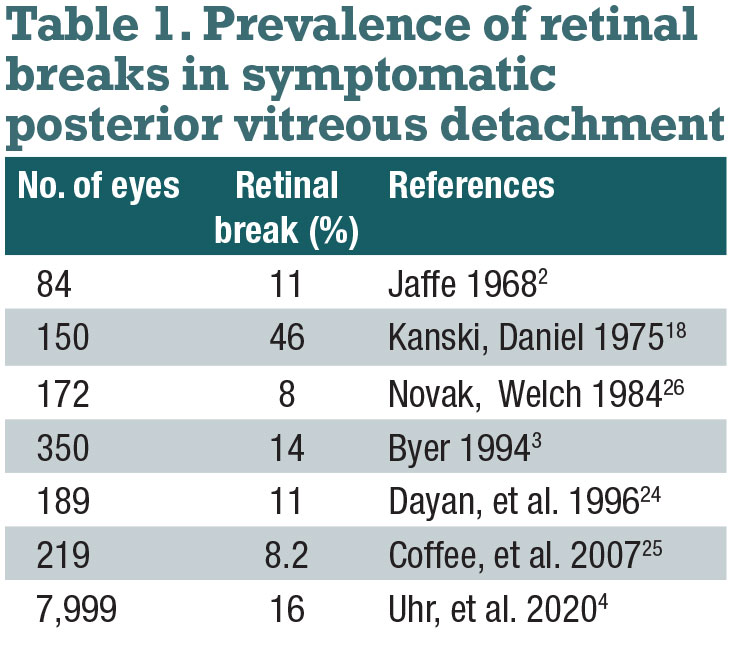

A retinal break is present in up to 16 percent of acute, symptomatic PVDs (Table 1).2-5 If no retinal break appears upon presentation of acute, symptomatic PVD, there’s a 2 percent rate of a retinal break in the subsequent weeks.1

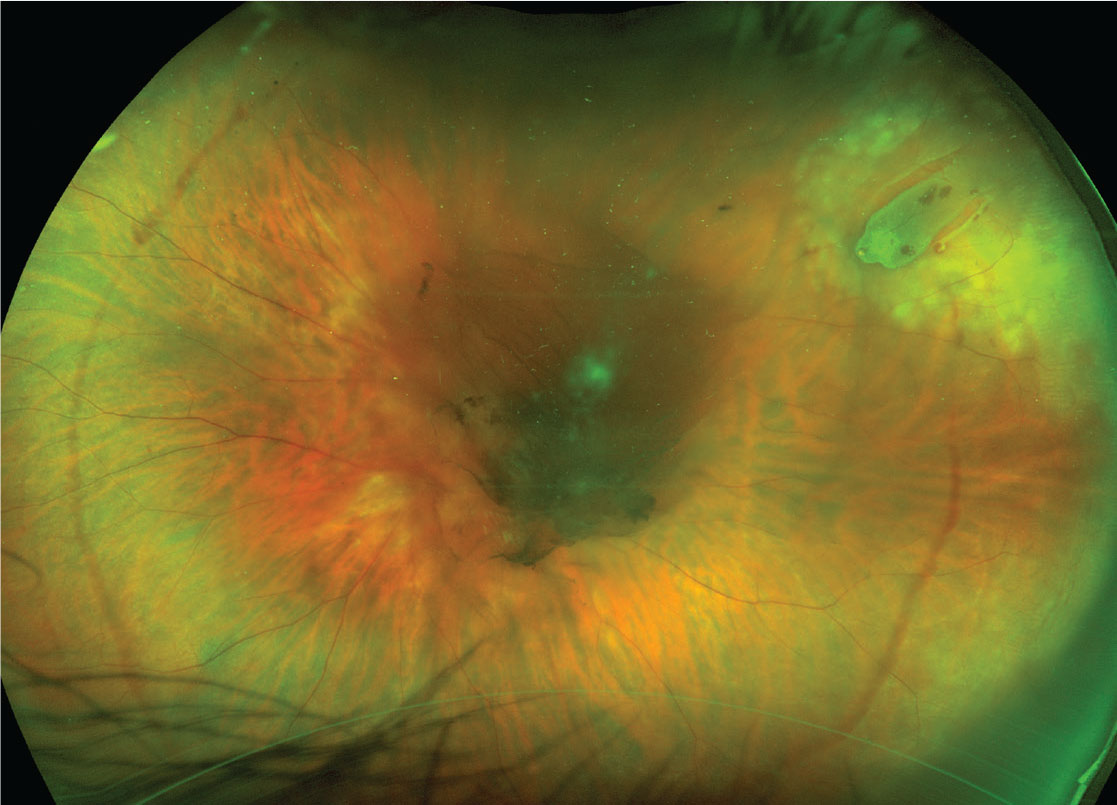

A Weiss ring, defined as peripapillary glial tissue suspended in the vitreous cortex, is present in about half of symptomatic PVDs with an associated retinal break.6 The likelihood of finding a retinal break is increased in the presence of a Shafer’s sign (90 percent )7,8 and/or vitreous hemorrhage (50 to 70 percent) (Figure 1).2,3

Other risk factors for retinal breaks include myopia, aphakia, pseudophakia, cataract surgery, lattice retinal degeneration, uveitis, retinitis, hereditary vitreoretinopathies and trauma.

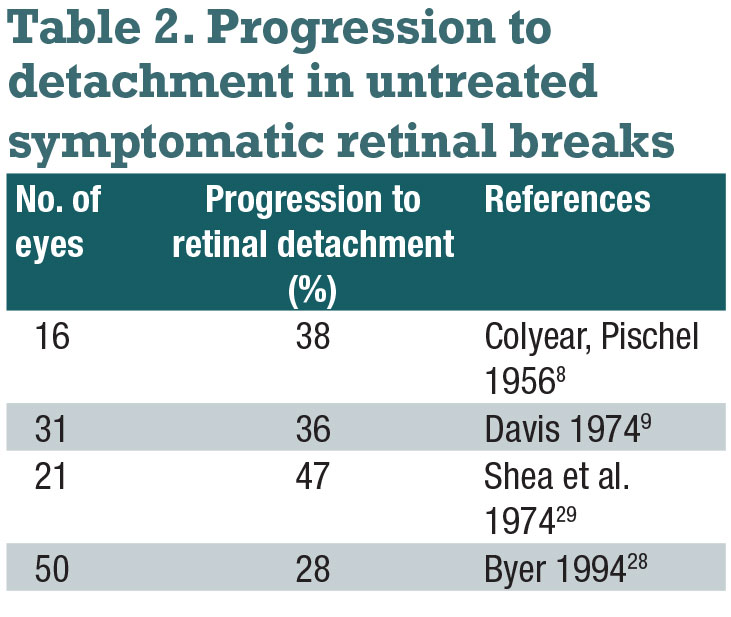

2. How often do symptomatic retinal breaks lead to RD without treatment?

|

Untreated, symptomatic horseshoe tears are reported to lead to RD in 30 to 50 percent of cases (Table 2).9,10 Retinal break features that are particularly high risk for progression to RD include breaks of acute onset, superior location, large size and surrounding subretinal fluid.

Some breaks are associated with subclinical RD, which is defined as an extension of subretinal fluid at least 1 disc diameter away from the break but not more than 2 disc diameters posterior to the equator. Operculated retinal breaks have a low risk of progression to RD because the operculum represents relief of the vitreoretinal traction.

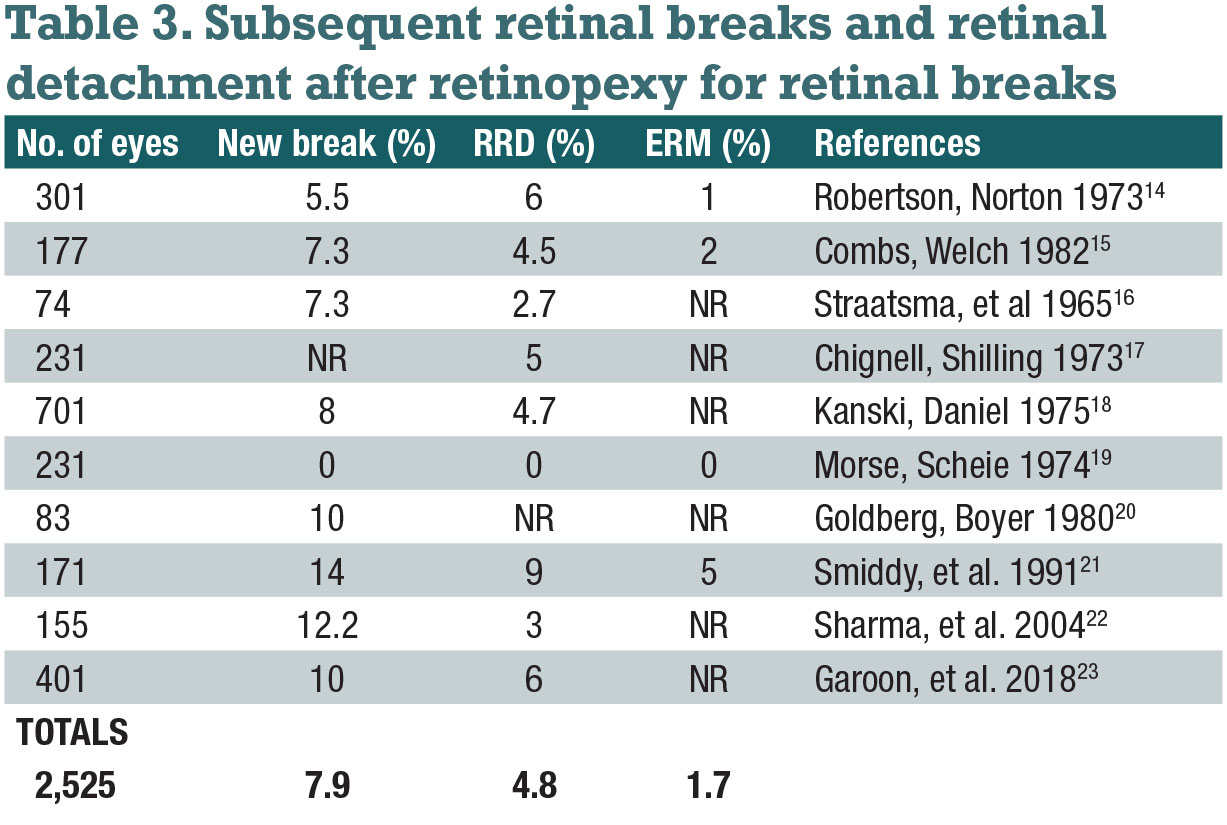

3. How often do subsequent retinal breaks occur after treatment of the first break?

Acute-onset, symptomatic horseshoe tears are generally treated in an effort to reduce the risk of progression to RD. Retinal breaks are treated with retinopexy by cryotherapy or laser photocoagulation. If severe media opacity prohibits either procedure, vitrectomy may be necessary.

Subsequent retinal breaks occur after treatment of the first retinal break in 5 to 14 percent of eyes (Table 3). About half of subsequent breaks occur within four to six weeks, but new breaks may occur months or even years later.5

|

| Figure 1. Symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment with retinal break. There is a central area of vitreous hemorrhage and peripheral hemorrhage that demarcate the circumferential extent of PVD. The break has a cuff of subretinal fluid. Laser photocoagulation burns barricade the break to the ora serrata. Visual acuity was 20/400. |

|

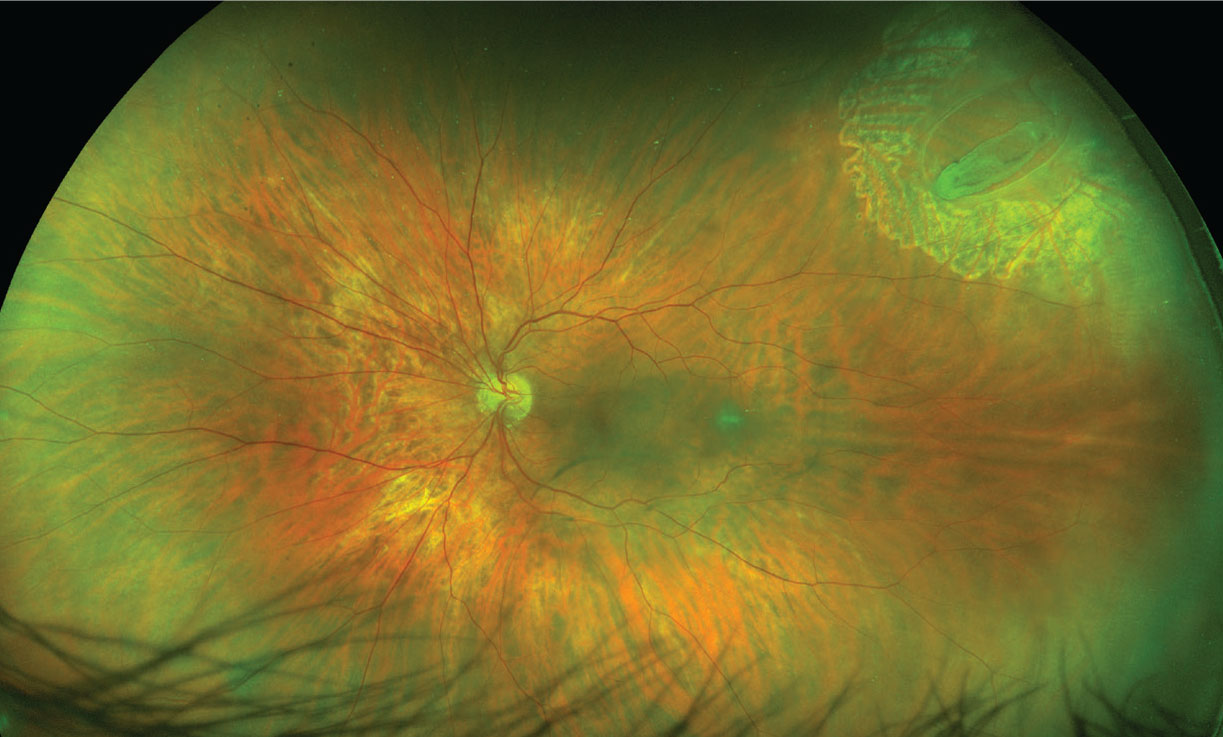

| Figure 2. Three months after retinopexy, no retinal detachment and no new retinal breaks have occurred, and the vitreous hemorrhage has resolved. Visual acuity is 20/20. |

4. How often do symptomatic retinal breaks lead to RD despite treatment?

|

RD occurs in about 5 percent of eyes with symptomatic retinal breaks despite retinopexy (Table 3). This can occur because of inadequate treatment to all margins of the break, if subretinal fluid accumulates before chorioretinal adhesion from retinopexy is complete, or because of missed or new breaks. Only about one-third of RDs occur within six weeks of treatment.5

5. How often do retinal breaks and RD occur in the fellow eye?

Fellow eyes in RD have an 8.4 percent rate of retinal breaks and a 14.5 percent rate of lattice retinal degeneration at presentation.11 The risk of RD in the fellow eye is 7 to 23 percent; 1 to 2 percent of eyes present with simultaneous bilateral RD.11,12

Prophylactic treatment of lattice degeneration in fellow eyes may reduce the risk of RD two- or threefold,13 although this has been debated because new retinal breaks often develop in untreated areas or may occur at the edge of retinopexy scars if a PVD occurs or extends.14

Management of symptomatic PVD

|

While there are no prospective, randomized controlled trials to guide management, it’s generally accepted that acute, symptomatic PVD merits evaluation with thorough ophthalmoscopy that usually includes scleral depression. If media opacity precludes complete ophthalmoscopy to the ora serrata, B-scan ultrasonography and frequent clinical reexamination are alternatives.

The risk of progression of asymptomatic breaks, even when horseshoe-shaped, to RD is exceedingly low, so they can generally be observed. However, acute and symptomatic horseshoe tears should be treated with retinopexy (Figure 2).

Retinopexy can be performed with either laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy. Retinopexy should encompass the entire margin of the retinal break and any associated lattice retinal degeneration. If this isn’t possible, retinopexy burns should surround the break extending to the ora serrata.

Giant retinal tears are generally treated with surgery. RD is usually treated with surgery, which may include pneumatic retinopexy, pars plana vitrectomy, scleral buckle or a combination of scleral buckle and vitrectomy.

Regardless of whether or not a patient presents with a retinal break and receives treatment, the potential for subsequent breaks or RD warrants longitudinal follow-up when possible. Detailed guidelines for follow-up have been published.1 Patients should also be clearly counseled that they need prompt reevaluation if they develop new symptoms of photopsias, floaters or visual field deficits—as opposed to persistence of existing symptoms.

Bottom line

Retinal breaks are a common, vision-threatening occurrence. Early recognition and treatment of acute, symptomatic retinal breaks will reduce rates of RRD and subsequent vision loss. Additional breaks can occur after treatment of the initial break and fellow eyes may also have similar events. Regular follow-up is indicated. RS

REFERENCES

1. Posterior vitreous detachment, retinal breaks, and lattice degeneration PPP – 2019. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Updated October 2019. https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/posterior-vitreous-detachment-retinal-breaks-latti Accessed March 4, 2021.

2. Jaffe NS. Complications of acute posterior vitreous detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968;79:568-571

3. Byer NE. Natural history of posterior vitreous detachment with early management as the premier line of defense against retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1503-1513.

4. Uhr JH, Obeid A, Wibbelsman TD, et al. Delayed retinal breaks and detachments after acute posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:516-522.

5. Goh YW, Ehrlich R, Stewart J, et al. The incidence of retinal breaks in the presenting and fellow eyes in patients with acute symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment and their associated risk factors. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila.) 2015;4:5-8.6. Brod RD, Lightman DA, Packer AJ, et al. Correlation between vitreous pigment granules and retinal breaks in eyes with acute posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1366-1369.

7. Tanner V, Harle D, Tan J, et al. Acute posterior vitreous detachment: The predictive value of vitreous pigment and symptomatology. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1264-1268.

8. Colyear BH Jr, Pischel DK. Clinical tears in the retina without detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1956;41:773-792.

9. Davis MD. Natural history of retinal breaks without detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;92:183-194.

10. Mitry D, Singh J, Yorston D, et al. The fellow eye in retinal detachment: Findings from the Scottish Retinal Detachment study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:110-113.

11. Gonzales CR, Gupta A, Schwartz SD, et al. The fellow eye of patients with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:518-521.

12. Folk JC, Arrindell EL, Klugman MR. The fellow eye of patients with phakic lattice retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:72-79.

13. Chauhan DS, Downie JA, Eckstein M, et al. Failure of prophylactic retinopexy in fellow eyes without a posterior vitreous detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:968-971.

14. Robertson DM, Norton EW. Long-term follow-up of treated retinal breaks. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;75:395-404.

15. Combs JL, Welch RB. Retinal breaks without detachment: Natural history, management and long term follow-up. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1982;80:64-97.

16. Straatsma BR, Allen RA, Christensen RE. The prophylaxis of retinal detachment. Trans Pac Coast Oto-Ophthalmol Soc Ann Meet. 1965;46:211-236.

17. Chignell AH, Shilling J. Prophylaxis of retinal detachment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1973;57:291-298.

18. Kanski JJ, Daniel R. Prophylaxis of retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79:197-205.

19. Morse PH, Scheie HG. Prophylactic cryoretinopexy of retinal breaks. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;92:204-207.

20. Goldberg RE, Boyer DS. Sequential retinal breaks following a spontaneous initial retinal break. Ophthalmology. 1980;88:10-12.

21. Smiddy WE, Flynn HW Jr, Nicholson DH, et al. Results and complications in treated retinal breaks. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:623-631.

22. Sharma MC, Regillo CD, Shuler MF, et al. Determination of the incidence and clinical characteristics of subsequent retinal tears following treatment of the acute posterior vitreous detachment-related initial retinal tears. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:280-284.

23. Garoon RB, Smiddy WE, Flynn HW Jr. Treated retinal breaks: Clinical course and outcomes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256:1053-1057.

24. Dayan MR, Jayamanne DG, Andrews RM, et al. Flashes and floaters as predictors of vitreoretinal pathology: Is follow-up necessary for posterior vitreous detachment? Eye. 1996;10:456-458.

25. Coffee RE, Westfall AC, Davis GH, et al. Symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment and the incidence of delayed retinal breaks: Case series and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:409-413.

26. Novak MA, Welch RB. Complications of acute symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97:308-314.

27. Kanski JJ. Complications of acute posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:44-46.

28. Byer NE. Natural history of posterior vitreous detachment with early management as the premier line of defense against retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1994;150:1504-1513.

29. Shea M, Davis MD, Kamel I. Retinal breaks without detachment, treated and untreated. Mod Probl Ophthalmol.1974;12:97-102.