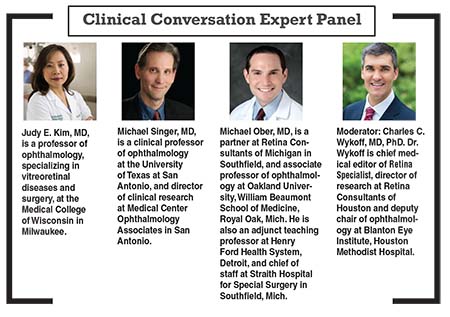

In the second part of this Clinical Conversation, Protocol U of the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network study1,2 provides a backdrop as Retina Specialist Chief Medical Editor Charles C. Wykoff, MD, PhD, leads our expert panel through a discussion of their approaches for using corticosteroids to manage

|

diabetic macular edema. The panelists discuss how Protocol U has influenced their approach to DME, including how they add the corticosteroid and timing. They also discuss how they manage intraocular pressure response to corticosteroid treatment.

Protocol U was a Phase II trial that evaluated the effectiveness of the dexamethasone intravitreal implant (Ozurdex, Allergan) in combination with anti-VEGF therapy for treatment of persistent DME.1,2

How Do You Use Corticosteroids in DME?

Dr. Wykoff asks the panelists if Protocol U has changed how they incorporate corticosteroids into their management of DME? The panelists concur that anti-VEGF treatment remains their first-line therapy for DME, but that corticosteroids have a place as second-line treatment

Judy E. Kim, MD, continues to use corticosteroids as a second-line therapy after a series of anti-VEGF injections in patients with persistent DME with intraretinal fluid or subretinal fluid. “Other patients

|

for whom I consider using steroids rather than anti-VEGF agents include patients who are pregnant or nursing, have had a recent stroke, or those who are pseudophakic and have no history of steroid-induced glaucoma but cannot come in on a frequent basis for anti-VEGF treatments,” she says.

Likewise, Michael Ober, MD, says anti-VEGF remains his first line therapy due to its safety profile. “I see Protocol U as a validation of my current regimen,” he says.

However, there is one exception in his approach: “If after several regular anti-VEGF treatments I don’t see the improvement I expect, I will give a steroid injection and then see the patient again one month later rather than combine the two treatments at once,” he says. “If in a month cystic changes and/or subretinal fluid have not improved significantly, I’ll supplement it with anti-VEGF monthly as needed.”

Michael Singer, MD, notes that he adds a corticosteroid when patients become sub-responders or non-responders either because of an anatomic issue, or because they can’t keep up their visits for anti-VEGF treatments or they get injection fatigue.

“I know, based on the work we’ve done in retinal vein occlusion that we’re able to get three to four months’ worth of treatment with a steroid,” Dr. Singer says. “Having that opportunity in the long term may increase compliance if they don’t have to come in as often.” He’ll also consider steroids to extend the treatment interval as the patient completes the first year of anti-VEGF therapy.

Logistics of Adding the Steroid

Dr. Singer uses a combination treatment like that employed in Protocol U. “I won’t do it on the same day for insurance reasons,” he says. He waits two weeks to see if the anti-VEGF injection has had an effect. “At two weeks some of these patients have persistent edema, and that lets me know if the anti-VEGF completely dried out the retina or at least started to,” he says.

The degree of retinal dryness is a marker of the cause of the edema, Dr. Singer says. “If the retina is only 20 percent dry after an anti-VEGF injection as opposed to 80 percent dry, that indicates it is more inflammatory-mediated,” he says. “If it’s more than 50 percent dry, it is anti-VEGF mediated, but the anti-VEGF agent is not strong enough. In these cases I’ll switch to a stronger anti-VEGF agent.”

Because DME has a vascular endothelial growth factor component, anti-VEGF

|

therapy always has a role in these patients, he says. “Treatment with anti-VEGF is going to handle the VEGF portion, even if it’s minor, and the steroid will handle the inflammatory component,” he adds.

Dr. Kim says she may switch from anti-VEGF to a monotherapy steroid. In some cases she favors combination therapy. “In some patients I will use the dexamethasone implant one month, then anti-VEGF for the second and third months, followed by dexamethasone again the following month,” she says. “However, I’m not doing combination therapy on the same day or within a week.” The dexamethasone implant lasts three months on average, but it can range from two to five months, she says.

Managing Side Effects

Dr. Wykoff notes that 29 percent of the combination group in Protocol U had increased IOP but none of the ranibizumab monotherapy arm did. The study duration was probably too short to adequately assess cataract progression.

Dr. Singer points out that the REINFORCE trial of the dexamethasone intravitreal implant had low percentages of patients with IOPs over 25 and 35 mmHg—8.2 percent and 1 percent, respectively.4 Overall, 22 percent of patients needed IOP therapy. He uses either monotherapy or combination drops to treat IOP, “and the vast majority of patients handle that well.”

Dr. Singer notes that, as the steroid wears off, the need for anti-glaucoma drop decreases. “Then when you give another steroid injection, you may have to keep them on the anti-glaucoma therapy,” he says.

Dr. Kim finds that about 20 percent of her patients on steroid therapy have increased IOPs, but, again, most respond to pressure-lowering drops. “Glaucoma surgery has only been needed in rare cases,” she adds.

Clinical Threshold for Drops

Key factors for starting a patient on IOP-lowering drops include the patient’s age, optic nerve appearance, history of glaucoma and baseline IOP, Dr. Ober says.

Those patients, he says, are “going to have a much lower threshold to begin IOP-lowering therapy than those without risk factors for glaucoma.” He frequently comanages these patients early with a glaucoma specialist if they need two or more drops. “The optic nerve evaluation or OCT nerve fiber layer interpretation can sometimes have more nuance to it,” he says.

When To Shift to Fluocinolone

Dr. Singer puts patients on fluocinolone when the treatment burden becomes an issue; that is, when injection fatigue sets in but the retina is very stable, and when he’s assured they are not going to have a significant IOP response after dexamethasone. “I monitor these patients carefully,” he says.

Some patients on fluocinolone may need supplemental therapy, but others may experience rebound edema. Dr. Singer notes he retreats those patients with rebound edema with an anti-VEGF injection. “In my experience, unlike with typical anti-VEGF injections that last only a month or two, patients on the fluocinolone implant can extend out anti-VEGF treatment to three to four months,” he says. “My hypothesis is that because the anti-VEGF injection only has to deal with the VEGF component, while the micro-dosing of the steroid seems to handle the inflammatory component.”

Dr. Kim goes to fluocinolone after the patient shows a good response to dexamethasone but must continue with treatment. “At that point, I switch to fluocinolone in order to reduce the treatment burden,” she says.

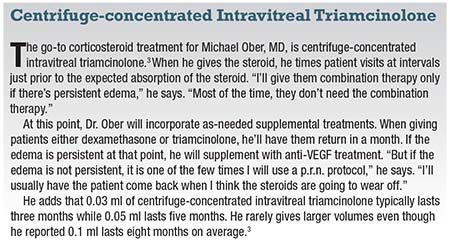

Dr. Ober opts instead for the centrifuge-concentrated triamcinolone in these situations (box, page 39). “That sort of works in lieu of the fluoconilone, and it’s much less expensive,” he says. This is the so-called slurry steroid that he originally reported in 2013. He uses Triesence. Susan Malinowski, MD, reported on the same technique using Kenalog.5 Says Dr. Ober, “I can give a dose as low as 0.01 ml. My standard dose is 0.03 ml; that will last usually three to four months.” RS

REFERENCES

1. Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Liu D, et al, for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Effect of adding dexamethasone to continued ranibizumab treatment in patients with persistent diabetic macular edema: A DRCR Network Phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:29-38

2. Phase II Combination steroid and anti-VEGF for persistent DME. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01945866. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01945866

3. Ober MD, Valijan S. The duration of effect of centrifuge concentrated intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide. Retina. 2013;33:867-72.

4. Fine HF, Singer M, Dugel PU, Capone A, Maltman J. Real-world assessment of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in diabetic macular edema; interim analysis from the Reinforce Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:ARVO E-Abstract 3259.

5. Malinowski S. Slurry Kenalog; a lower cost, quick and easy alternative for long-term intraocular steroid delivery. Paper presented at American Society of Retina Specialists 35th annual meeting, Boston, MA; August 13, 2017.