|

|

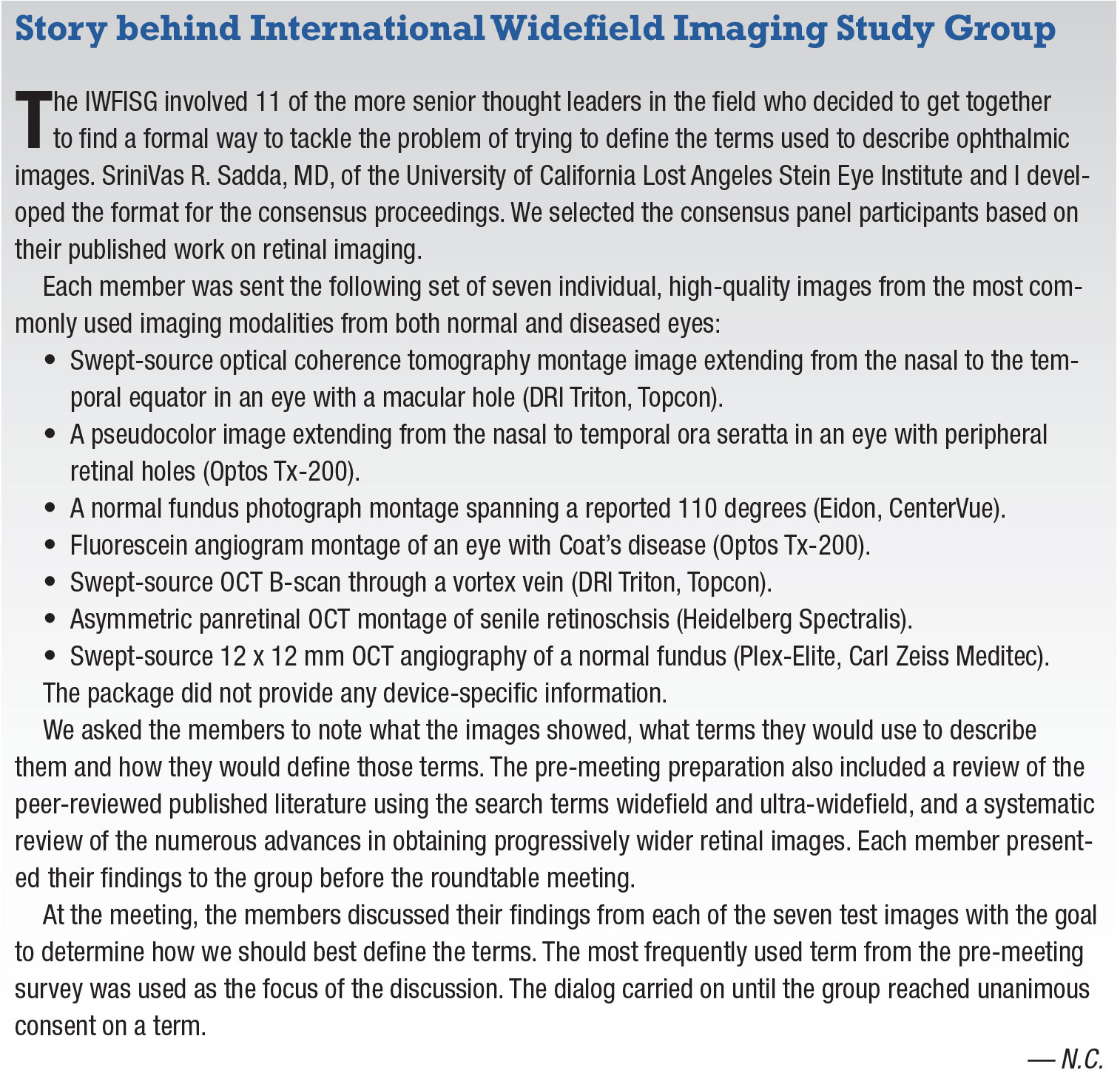

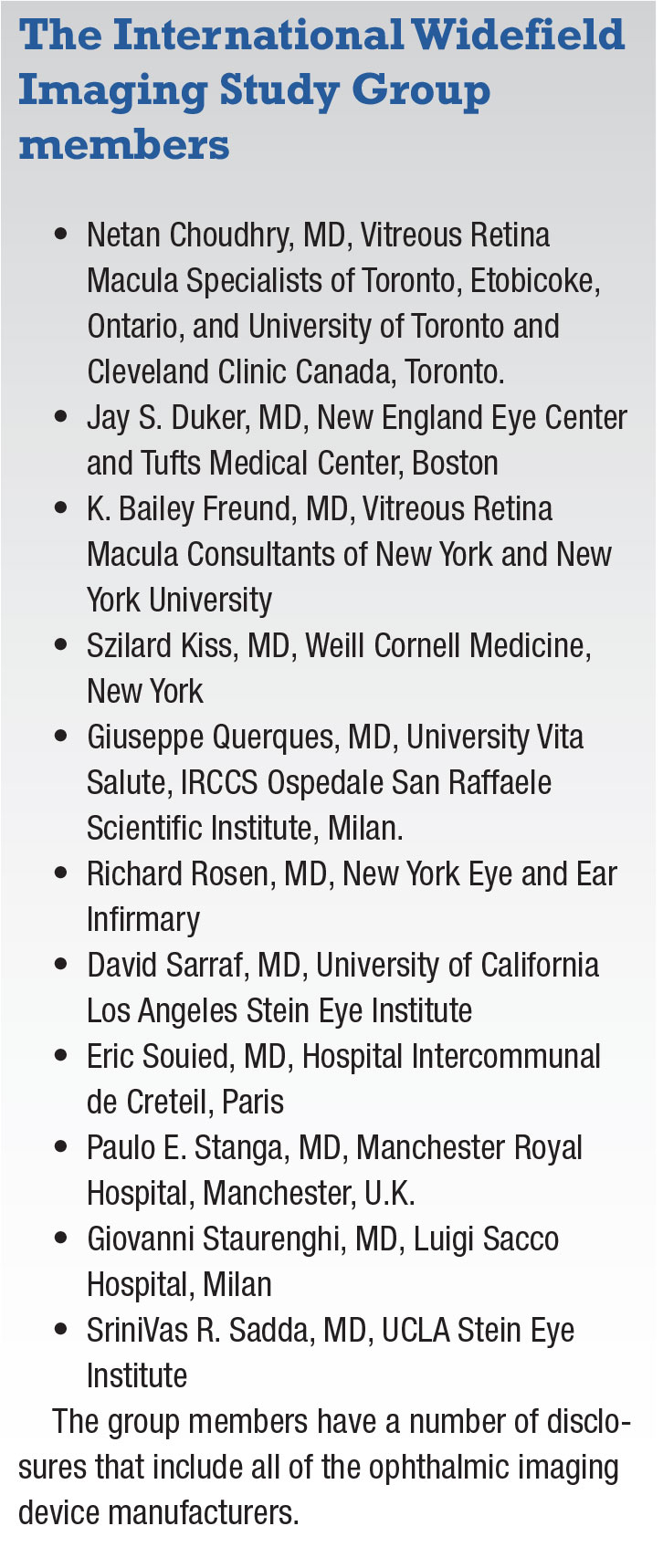

The recommendations for terminology for ophthalmic imaging by the International Widefield Imaging Study Group, published online in October in Ophthalmology Retina,1 had been highly anticipated.

As the lead author of those findings, Retina Specialist Magazine has asked me to provide some context on what those findings mean for us in the clinic.

This study group came together because over the last several years a great deal of confusion in the literature has surrounded the terminology for describing images captured by the various modalities we have at our disposal: color fundus photography; fluorescein angiography; autofluorescence; indocyanine green angiography; optical coherence tomography (OCT B-scans); and en face OCT angiography.

Most prominent among these are the terms widefield and ultra-widefield. Manufacturers have used their own terminology and that has had some influence on the nomenclature researchers have used in their papers. However, this is an area in which there’s never been a consensus of how we define these terms. Reaching that consensus was the goal of this group.

Examples of unclear terminology

Here are two examples of the confusion that has existed. An article that reports on an OCT scan that doesn’t go beyond the arcades to acquire a full view of the retina and uses the term widefield enface imaging isn’t really giving us the full perspective. The reader may then associate the term widefield with that field of view, but the image doesn’t even show half of the retina, or maybe even more than half.

Or take an OCT that doesn’t show a single line scan of a lesion in the far periphery. Would that be considered a widefield or ultra-widefield view, or neither? So the question is, how do we unify our language so we’re all saying the same thing in the literature?

Key definitions

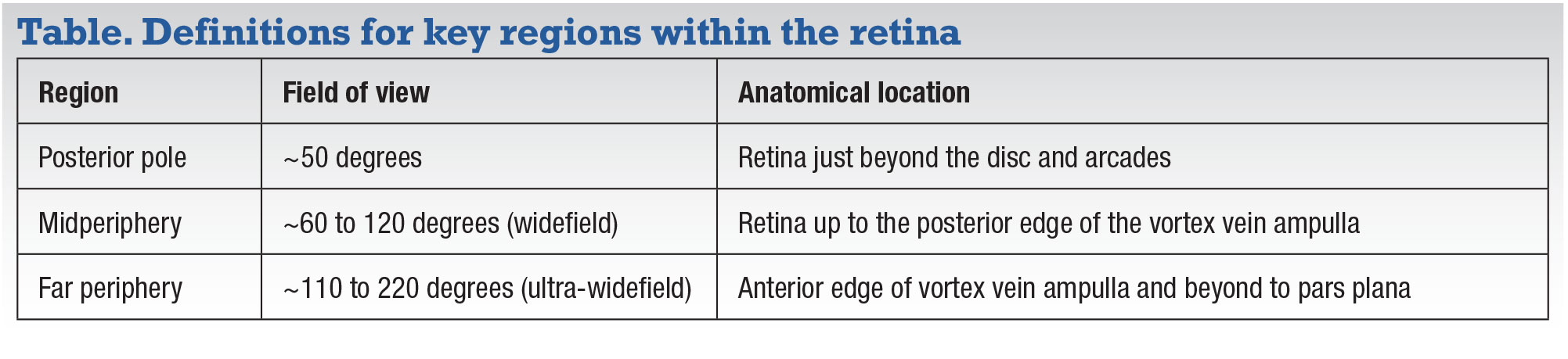

The anatomical features integral to the IWFISG’s recommendations are the four vortex veins that most, although not all, patients have. The definitions for fundus photography, angiography and AF the group has suggested are:

- Posterior pole—retina within the arcades and just slightly beyond them.

- Midperiphery—region of the retina up to the posterior edge of the vortex vein ampulla.

- Far periphery—region of the retina anterior to the vortex vein ampulla.

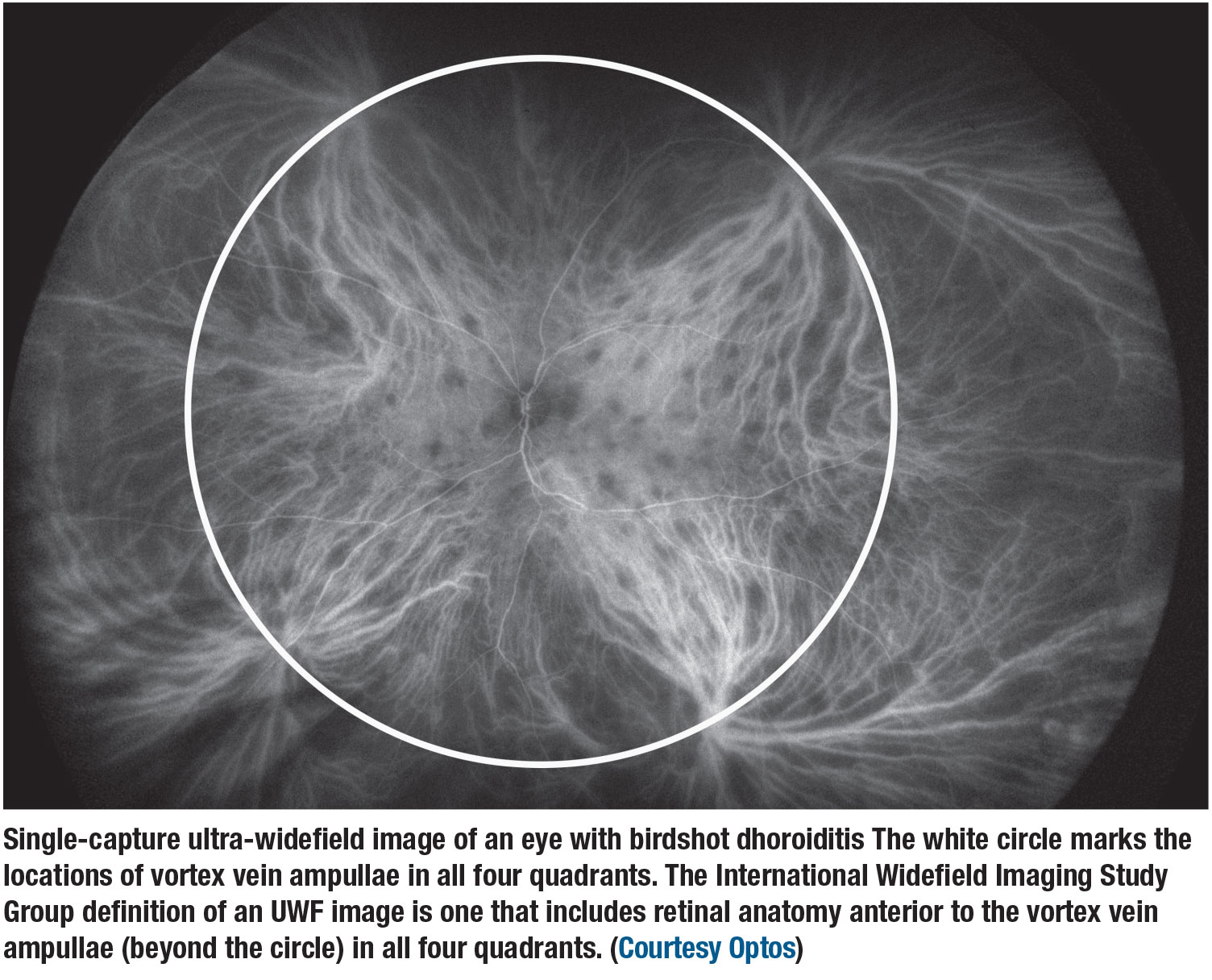

- Widefield—single-capture image centered on the fovea and capture the retina in all four quadrants, posterior to and including the vortex vein ampullae.

- Ultra-widefield—single-capture view of the retina in the far periphery in all four quadrants.

- Panretinal—a single-capture, 360-degree ora-to-ora view of the retina.

|

For OCT, the definitions vary somewhat. For OCT B-scans, the following principles apply:

- They’re used primarily for cross-sectional examination of the retina.

- Field of view does not apply.

- Scans are defined in terms of scan length (mm).

- Pixelation and aspect ratio may vary among scans.

- No single scan can universally define a widefield OCT scan.

The description should include:

- scan size;

- location;

- scan type;

- whether or not it is a montage; and

- symmetry.

For OCTA scans, the key definitions are slightly different:

Widefield—retina in all four quadrants and include the retina up to the posterior edge of vortex vein ampullae.

Ultra-widefield—retina in all four quadrants beyond the anterior edge of the vortex vein ampullae.

|

|

Field of view

These definitions are predicated on the definition of field of view; that is, the macula should be at the center of the image, and the cut points should correspond to commonly visualized anatomical features—the vortex vein ampullae. The IWFISG also made recommendations for key regions within the retina (Table, page 27).

|

There are variations on these definitions:

Asymmetric widefield or ultra-widefield—an image that captures only the temporal, nasal, superior or inferior aspects of the retina.

Montage—a scenario where photographers take multiple images and stitch, or montage, them together to provide the full perspective, but this isn’t really a single-capture image; this is, instead, widefield montage, indicating that it was put together by multiple images.

Some of this becomes academic but descriptive because in retinal imaging we describe findings. From the reader’s or investigator’s perspective, it creates a roadmap as to how a particular image was captured.

There are caveats. Montaging images involves image overlap, and sometimes data may be lost. But a single-capture image does not in theory lose data. The editing process to create a montage image may inadvertently leave out some details. So an image that’s called simply a widefield photograph implies single-image capture.

|

OCT-specific definitions

In OCT applying the anatomical boundaries for widefield or ultra-widefield definitions can be difficult because OCT doesn’t capture all four vortex veins in all four quadrants. So the IWFISG felt that the descriptions for OCTs should be based on the length of the scan—9, 16 or 23 mm—and then, again, also to indicate whether a montage was used, and whether it’s a structural B-scan that shows only the anatomy, or a full B-scan that shows blood flow, such as that seen with OCT angiography

And then, the IWFISG felt the terminology must also address the region the scans capture. A scan of the macula that’s part of the posterior pole would be a 9-mm, posterior pole, structural B-scan. An image farther out in the periphery toward the pars plans would be a 3-mm, far peripheral, structural B-scan. These descriptions tell the reader the region of the retina the scan is from, the length of the scan and whether the scan is showing structure or flow.

Describing images has become so complicated only because our technology is advancing rapidly and our modalities are expanding. We must be descriptive in how we communicate with each other. It’s not that different from the way radiologists describe MRI and CT-scans. They’re very descriptive of whether it’s a diffusion-weighted image, whether dye has been used, where the cuts are, or whether it’s a coronal scan or a sagittal scan.

Are manufacturers on board?

The IWFISG has shared our consensus definitions with the manufactures of these devices. We purposefully included all the different manufacturers’ images to eliminate bias in our findings. Ultimately, it’s the physicians and the discipline of rational medicine that defines how we choose to describe these terms. Hopefully, industry will follow and respect the definitions that we’re putting forward, and, at the same time, work internally to try to achieve that panretinal image. That’s really the holy grail for all of us as practitioners. If we can capture all the data in one image, we can walk through our patient day quickly and provide the greatest amount of information.

|

What’s next for IWFISG

The next action for the group is to continue to evaluate new technologies together and help position them in terms of where they fit into our practice, how we would define them and what their strengths and limitations are. As new technology emerges and new machines come out, we will be able to provide feedback on where they’re strong, where they need to be improved and where they’re best utilized. We have many great devices from many great manufacturers, and each device has a unique niche and a unique position in the work that we do.

Bottom line

No two devices are alike. Each has a strength, whether it’s an ability to capture an image quickly, the quality of the image, the software, the analytics, the speed of use, patient preference or comfort, they all vary in a variety of ways. Side-by-side comparisons of all devices are challenging, so the study group’s recommendations for terminology are all the more important. RS

|

REFERENCE

1. Choudhry N, Duker HS, Freund KB, et al. Classification and guidelines for widefield imaging: Recommendations from the International Widefield Imaging Study Group. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3:843-849.