|

Bios DISCLOSURES: |

A 33-year-old male who recently returned from a trip to Pakistan was evaluated in the emergency department at our tertiary referral center for four weeks of left eye irritation, light sensitivity, floaters, photopsias and blurred vision.

An outside ophthalmologist diagnosed him with posterior uveitis and Quanti-FERON-TB Gold test returned positive on a laboratory workup. He was referred to infectious disease and started on rifampin for latent tuberculosis therapy, along with prednisone 80 mg daily. His vision continued to deteriorate until he was referred to our emergency department.

Examination findings

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and count fingers in the left eye. Intraocular pressure was normal in both eyes. There was no afferent pupillary defect.

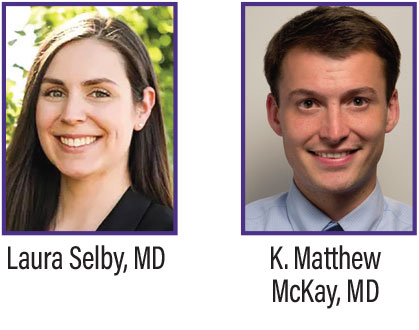

Slit lamp examination of the right eye was normal. The left eye had rare cells in the anterior vitreous. A dilated fundus examination revealed multifocal, deep, creamy, whitish lesions contiguous with the optic nerve. Additional active-appearing lesions surrounded an area of multifocal scarring in the inferior retina (Figure 1A).

Workup

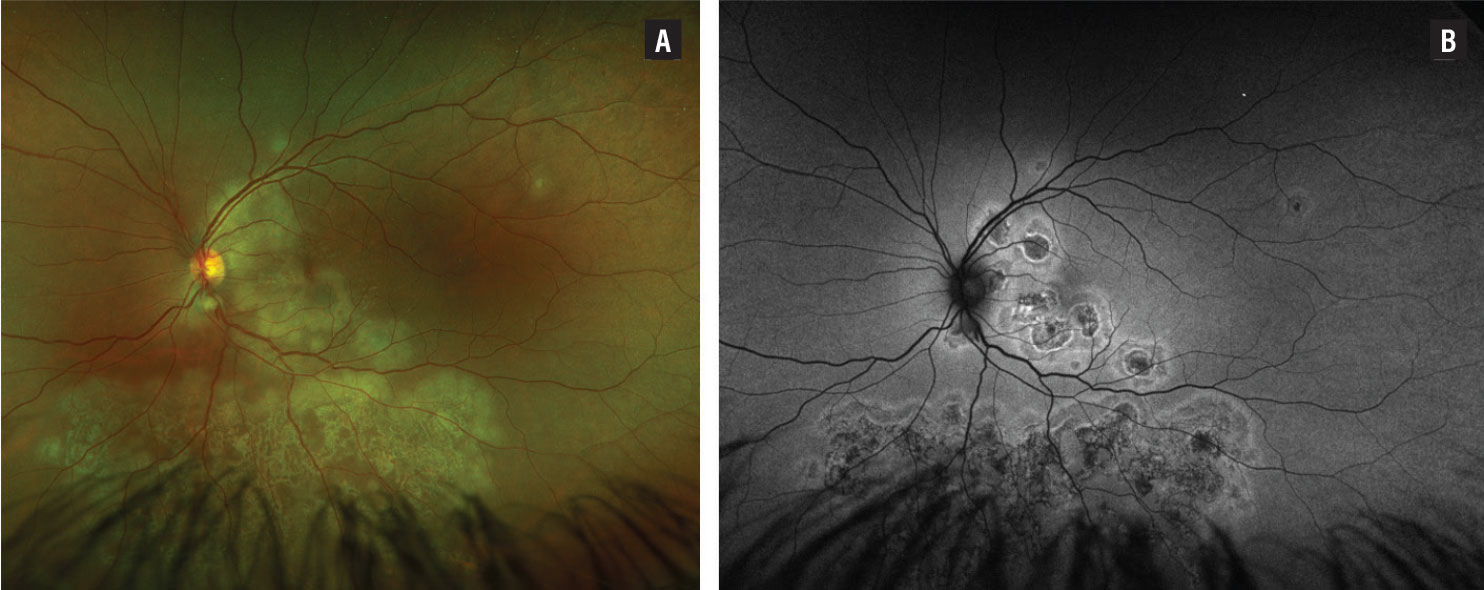

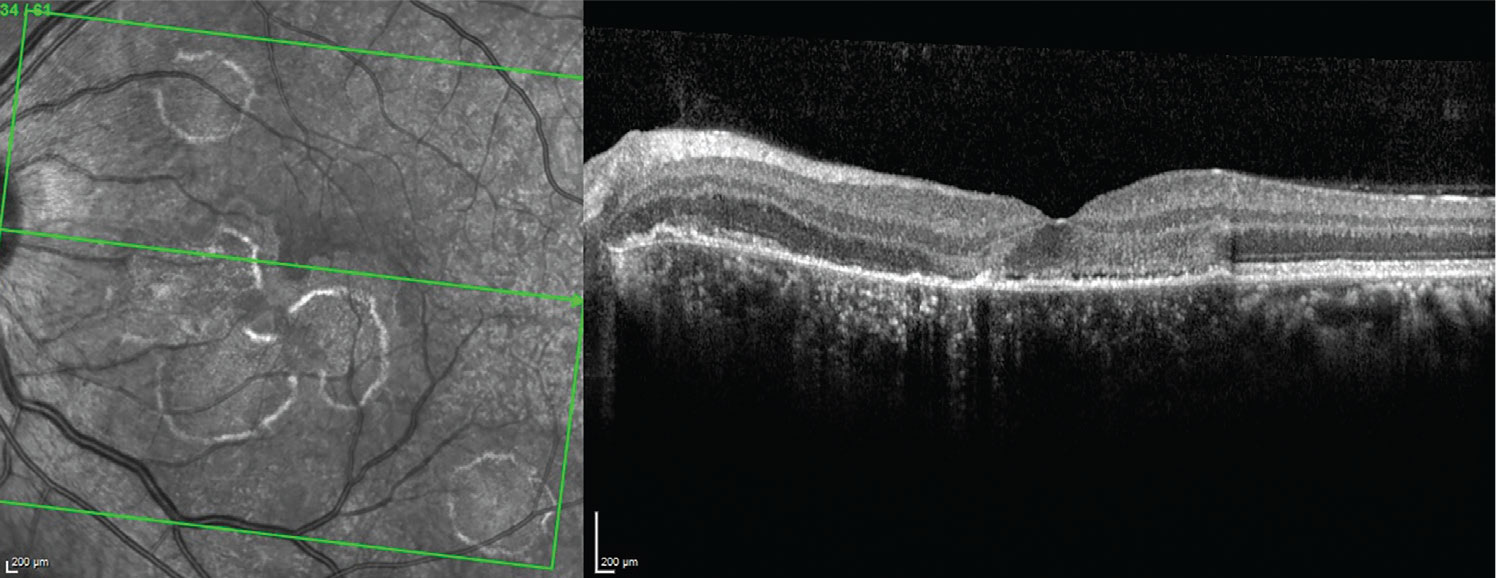

Fundus autofluorescence showed multifocal hypoautofluorescent lesions with surrounding hyperautofluorescence (Figure 1B). Optical coherence tomography showed attenuation of the retinal pigment epithelium, patchy loss of the ellipsoid zone and photoreceptors, and thickened and disorganized retinal laminations (Figure 2). Fluorescein angiography showed early blocking in the areas of the active choroidal lesions and late staining (Figure 3).

Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within normal limits. Syphilis screen and HIV were both negative, and a chest X-ray was unremarkable. QuantiFERON-TB Gold was positive.

|

|

Figure 1. A) Color fundus photo of the left eye shows multifocal, deep yellowish choroidal lesions both in the posterior pole and inferior mid-periphery with central scarring and active-appearing edges. B) Fundus autofluorescence of the left eye demonstrates multifocal hypoautofluorescent lesions with surrounding hyperautofluorescence. |

|

|

Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography of the left macula demonstrates ellipsoid zone loss, patchy photoreceptor layer loss, attenuation of the retinal pigment epithelium and thickened and disorganized retinal laminations. |

|

|

Figure 3. A) Fluorescein angiography of the left eye at 16 seconds shows patchy areas of early blocking in the macula and inferior mid-periphery. B) At 6:37 FA demonstrates late staining of those same areas corresponding with active lesions. Progressive staining of an inactive scar was also observed in the macula and inferior periphery. |

Diagnosis and management

We suspected serpiginous-like choroiditis and started the patient on four-drug therapy for tuberculosis: rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. We continued the prednisone 80 mg daily, and later initiated tacrolimus and azathioprine for progression of the inflammatory lesions.

Discussion

TB can affect multiple organs throughout the body, although ocular involvement is rare, occurring in approximately 0.2 to 2.7 percent of cases in nonendemic regions.1,2 Ocular TB presents in a variety of ways, which can make diagnosis difficult.

However, distinguishing tubercular uveitis from idiopathic uveitis is of utmost importance because lack of appropriate treatment in these cases threatens vision. Additionally, failure to consider tuberculosis as a potential cause of intraocular inflammation and treatment with immunosuppressive therapy can lead to death in patients with active TB.3

Tubercular choroiditis is the most common manifestation of posterior uveitis TB causes. One phenotype of tubercular choroiditis is serpiginous-like choroiditis (SLC), which is characterized by multifocal yellowish lesions with a serpiginoid appearance that lead to progressive scarring. Patients with SLC are more likely to be from tuberculosis endemic regions, have unilateral involvement with multifocal lesions, and be younger at the time of presentation.4

Treatment of SLC involves antitubercular therapy (ATT) and corticosteroids starting with or shortly after initiating ATT.5 In our patient, antitubercular therapy and oral prednisone wasn’t enough to control the aggressive and vision-threatening inflammation leading to initiation of additional immunosuppressive therapy.

Bottom line

Consider tuberculosis in patients from an endemic region who have posterior uveitis. Serpiginous-like choroiditis is one form of ocular tuberculosis that requires prompt initiation of antitubercular therapy. RS

REFERENCES

1. Testi I, Agrawal R, Mehta S, Basu S, Nguyen Q, Pavesio C, Gupta V. Ocular tuberculosis: Where are we today? Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:1808-1817.

2. Ang M, Chee SP. Controversies in ocular tuberculosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101:6-9.

3. Vianna RNG, Vanzan V, da Fonsêca MLG, Cravo L. Unilateral macular serpiginous-like choroiditis as the initial manifestation of presumed ocular tuberculosis. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2021;7:1.

4. Dutta Majumder P, Biswas J, Gupta A. Enigma of serpiginous choroiditis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:325-333.

5. Agrawal R, Testi I, Mahajan S, et al; Collaborative Ocular Tuberculosis Study Consensus Group. Collaborative Ocular Tuberculosis Study consensus guidelines on the management of tubercular uveitis-report 1: Guidelines for initiating antitubercular therapy in tubercular choroiditis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:266-276.