|

Bios Dr. Fortenbach is an DISCLOSURES: The authors have no relevant disclosures. |

A 53-year-old woman with a medical history of metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma came to the emergency department at our tertiary referral center with a new scotoma and painful eye movements in the left eye for one week.

She was diagnosed with cancer two years earlier. At that time, she developed fatigue, dyspnea, night sweats and significant anemia, and lost 30 pounds. Imaging revealed multiple pulmonary nodules, osteolytic spinal lesions, and a 5-x-4-cm left renal mass, which was determined to be a poorly-differentiated renal clear cell carcinoma after core needle biopsy.

She underwent four cycles of ipilimumab and nivolumab followed by monthly maintenance nivolumab infusions with an excellent response. At the time of presentation for her ophthalmic complaints, she continued on maintenance nivolumab and her cancer was in remission.

Ocular and vision assessment

She reported being in her usual state of health until the acute onset of blurry vision and development of a paracentral scotoma in her left eye. She denied floaters, photopsias or curtains in either eye. She had no history of eye trauma and no symptoms in her right eye.

She had no history of eye surgery or penetrating trauma. She reported mild tinnitus. A comprehensive review of systems revealed a hypopigmented rash on her back extending to her umbilicus. She was sexually active with her partner and had no history of sexually transmitted infection.

Examination findings

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/200 in the left. Intraocular pressures were normal. A trace relative afferent pupillary defect was in the left eye. Extraocular movements were full with mild pain with movement in the left eye.

Confrontation visual fields were full. Color vision testing by Ishihara plates were full in the right eye and reduced in the left. Slit lamp examination was notable for granulomatous keratic precipitates in the left eye with minimal flare and grade 0.5+ cell in the anterior chamber per the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature in both eyes.1

Neither eye had hypopyon, but the left eye had rare vitreous cells. Dilated fundus examination revealed striae radiating from the optic nerve head along with mild blurring of the nasal optic disc margin of the left eye. We noted a macula-sparing serous retinal detachment inferotemporally in the right eye and a macula-involving serous retinal detachment in the left. We didn’t observe any retinal tears on scleral depressed examination.

|

|

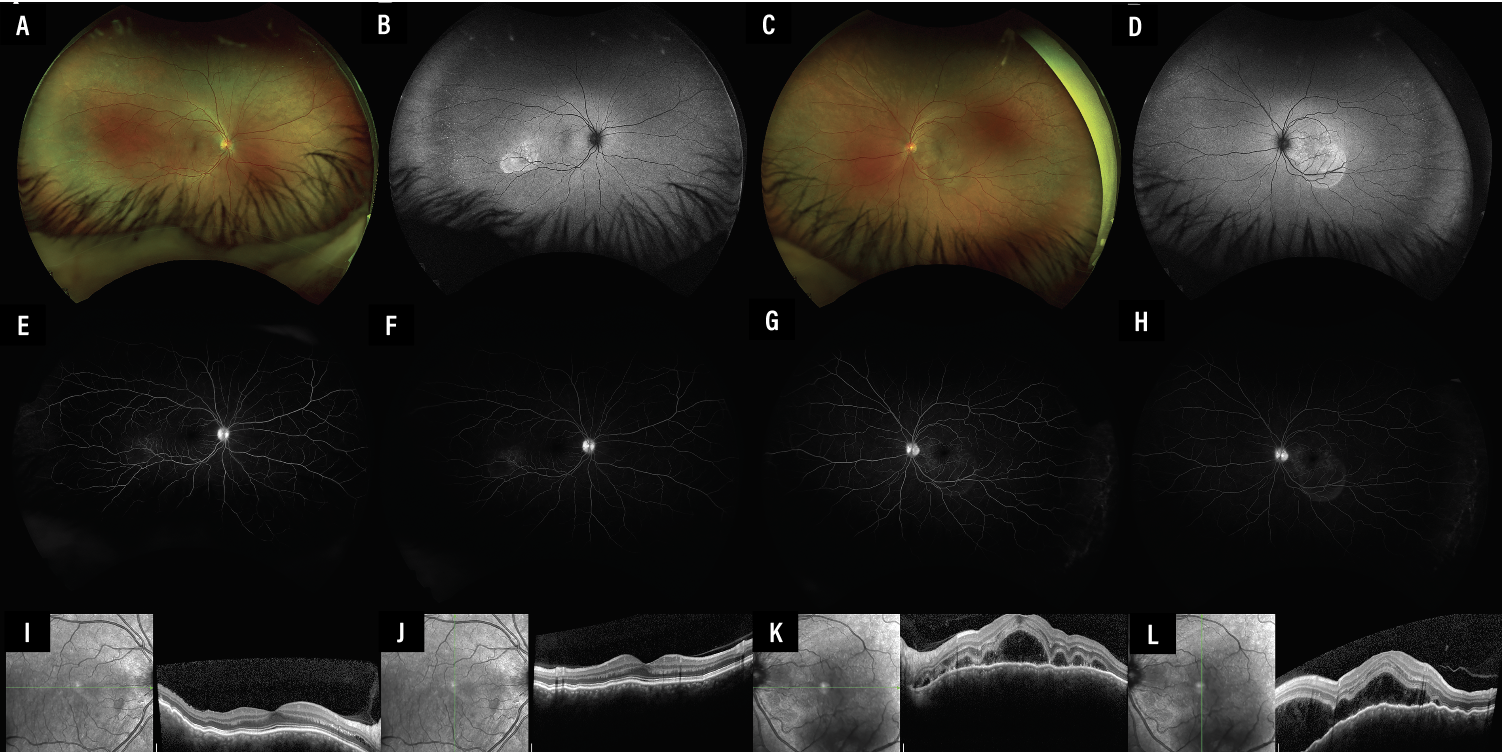

Figure 1. Multimodal imaging of the right eye (A, B, E, F, I, K) and left eye (C, D, G, H, J, L) at presentation. Scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (A, C) shows an area of mild inferotemporal subretinal fluid, better seen with corresponding fundus autofluorescence (B, D) as round regions of hypoautofluorescence. Fluorescein angiography in the right eye shows early (E) and late (F) pooling of the corresponding lesion as do similar images in the left eye (G, H). Optical coherence tomography horizontally and vertically enhanced depth imaging scans through the fovea in the right (I, J) and left (K, L) eyes show an irregular retinal pigment epithelium and thick choroid, with central subretinal fluid extending inferiorly in the left. |

Work-up

MRI of the brain and orbits showed no intracranial metastasis or optic nerve enhancement, although it did show some enhancement attributed to nonspecific inflammatory changes in the posterior left globe. An infectious and autoimmune work-up was negative.

B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated a thick choroid in the left eye without vitreous opacities. The choroidal thickness was normal in the right eye. Optical coherence tomography of the optic nerve retinal nerve fiber layer showed increased thickness in the left eye and normal thickness in the right. OCT of the macula showed a corrugated retinal pigment epithelium and notable choroidal thickening in both eyes.

We noted mild inferotemporal subretinal fluid not seen on OCT. The left eye had moderate subretinal fluid centrally and inferotemporally (Figure 1, above).

Diagnosis and management

We diagnosed the patient with bilateral nivolumab-induced Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada-like uveitis with mild papillitis in the left eye. She was admitted to the hospital and started on difluprednate drops every two hours.

We consulted the hematology-oncology service, who agreed with our recommendation to start the patient on intravenous steroids. Following a discussion with the patient and the oncology service, the patient elected to discontinue her nivolumab. She underwent three days of treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone 750 mg and was ultimately discharged with a difluprednate taper and a prolonged prednisone taper.

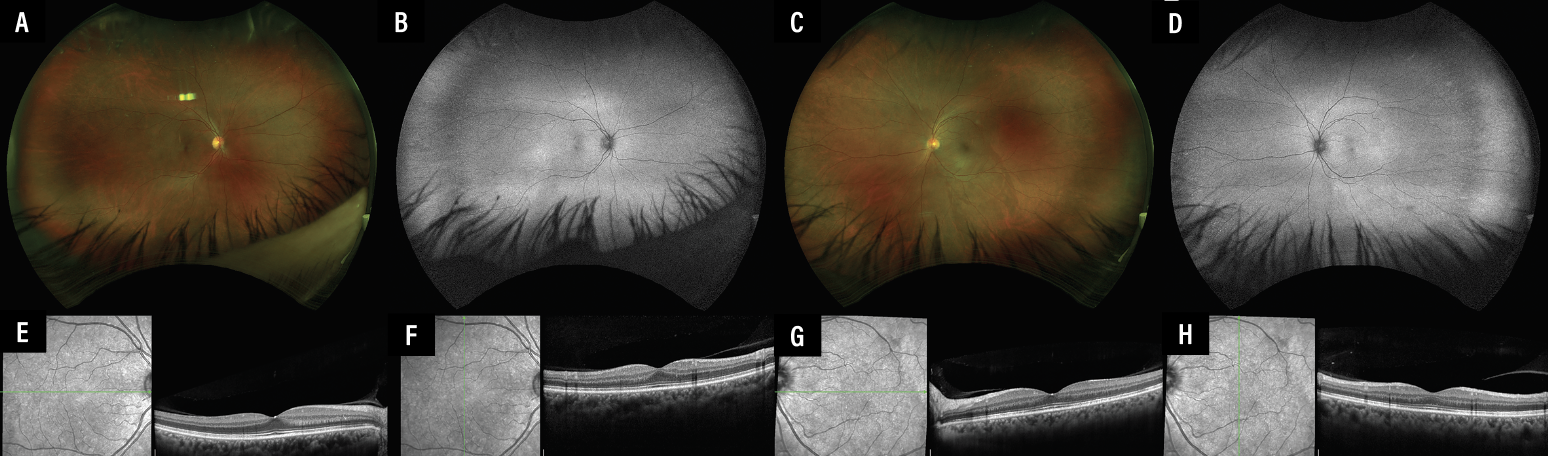

At the two-month follow up, she had complete resolution of the bilateral exudative retinal detachments and disc edema. Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes (Figure 2).

|

|

Figure 2. Multimodal imaging of the right (A, B, E, F) and left (C, D, G, H) eyes two months after intravenous methylprednisolone, topical steroids and cessation of nivolumab. Scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and fundus autofluorescence images of the right (A, B) and left (C, D) eyes show resolution of the subretinal fluid. Optical coherence tomography vertical and horizontal enhanced-depth imaging scans through the fovea of the right (E, F) and left eyes (G, H) show resolution of the retinal pigment epithelial irregularities, choroidal thickening and subretinal fluid, with some persistent patchy ellipsoid irregularity in the left eye. |

Discussion

Ipilimumab and nivolumab are immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), a class of novel anti-tumor medications used to treat various cancers, including lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma and metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Per the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium, nivolumab and ipilimumab are considered first-line therapies for advanced renal cell carcinoma.2

A recent meta-analysis of patients on nivolumab and ipilimumab for advanced renal cell carcinoma showed significant prolongation of progression free survival (hazard ratio = 0.73, 95% confidence interval 0.54 to 0.99, p = 0.04) and overall survival (HR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.78, p < 0.001).3

Other cases described ocular and orbital complications of ICIs, including Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada-like uveitis after starting nivolumab for renal cell carcinoma.4,5

Our patient met the revised diagnostic criteria for early complete Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease.6 She had no prior intraocular surgery or penetrating eye injury and no other clinical or laboratory evidence suggestive of an alternate ocular disease, but she did have bilateral serous retinal detachments with anterior uveitis and left-sided vitreous inflammation and mild papillitis, mild tinnitus and a hypopigmented rash on her back. Papillitis isn’t included in the diagnostic criteria of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, although it’s thought to be from juxtapapillary choroidal inflammation or inflammatory infiltration of the optic nerve.7

The general treatment of ICI uveitis involves topical, intravitreal or systemic steroids with or without cessation of the offending agent. Cessation of the offending medication must be discussed with the patient and the patient’s primary oncologist.

In 2018 the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Society of Clinical Oncology created guidelines for ICI-associated uveitis,8 outlining criteria for referral to ophthalmology and suggested treatment of uveitis. In some cases, the uveitis can be treated with local or systemic steroids or immunomodulatory therapy without discontinuing the ICI. The ophthalmologist must work closely with the oncologist in making treatment decisions to ensure appropriate ongoing cancer therapy and vision preservation.

In patients with active metastatic disease or progressive cancer, immunotherapy may be the best life-prolonging therapy or when an alternate intervention may not exist. The use of systemic steroids should also be approved by the patient’s oncologist. Our patient had an excellent outcome with topical and systemic steroids and cessation of nivolumab. RS

REFERENCES

1. Jabs DA, RB, Rosenbaum JT. Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–516.

2. Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: Extended follow-up of efficacy and safety results from a randomised, controlled, Phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1370–1385.

3. Zhang S, Xu X, Chen J, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab for advanced renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oncol. 2022;2022:5430525.

4. Ng CC, Ng JC, Johnson RN, et al. Nivolumab-induced Harada-like uveitis with bacillary detachment mimicking choroidal metastasis. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2023;17:233–238.

5. Czichos C, Wawrzynów B, Chamalis C, von Jagow B. [Bilateral Nivolumab-associated Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada-like Uveitis in a Patient with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma]. Article in German. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2021;238:711–714.

6. Read RW, Holland GN, Rao NA, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: Report of an international committee on nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:647–652.

7. Shoughy SS, Tabbara KF. Initial misdiagnosis of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2019;33:52–55.

8. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Thompson JA. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline summary. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:247-249.