Most retina specialists use intravitreal anti-VEGF injections as first-line management for diabetic macular edema, relegating intravitreal steroids to bei

|

ng second-line agents. Importantly, however, a clinically meaningful proportion of patients—32 to 66 percent1—will have persistent DME following at least six monthly intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.

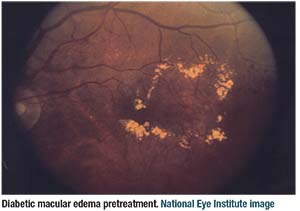

About DRCRnet Protocol U

Protocol U of the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network study was a Phase II trial that evaluated the effectiveness of the dexamethasone intravitreal implant (Ozurdex, Allergan) in combination with anti-VEGF therapy for treatment of persistent DME.2,3 The study involved 129 eyes. Eligible patients had to receive at least three anti-VEGF injections within 20 weeks of study enrollment and have persistent diabetic macular edema with 20/32 or worse visual acuity.

At enrollment, patients were entered into a run-in phase in which they were treated with three monthly injections of ranibizumab (Lucentis, Roche/Genentech). If, after the run-in phase, the eye still met inclusion criteria, it was randomized into one of two treatment arms: ranibizumab; or ranibizumab plus dexamethasone at baseline, and then monthly visits with as-needed ranibizumab retreatment in both arms. The combination arm was eligible for a second dexamethasone implant beginning at month three. The primary outcome of Protocol U was change in mean visual acuity at six months.

In this Clinical Conversation, Retina Specialist Chief Medical Editor Charles C. Wykoff, MD, PhD, moderates a panel of experts discussing the findings of the Phase II Protocol U trial and their implications for clinical practice.

In this first of two parts, the panelists discuss what Protocol U reveals about appropriate treatment loads and the role of anatomic data in directing therapy. In the second part, to appear in the June issue of Retina Specialist, the panel will discuss specific strategies for using corticosteroids in the DME patient and how to manage side effects.

Do Physicians Undertreat Persistent DME?

Dr. Wykoff notes that, following the run-in phase of Protocol U, approximately one-third of eyes became ineligible for ultimate randomization into the core part of the trial because their persistent DME resolved. He asks, is that a reflection of the belief that in clinical practice, physicians are often undertreating persistent or active DME?

“There are two ways to look at that,” says Michael Ober, MD. “The first is, there is a large percentage of under-treated patients, especially in the DME population; on average, these are younger patients. The second is that patients with DME take much longer to plateau in terms of visual and anatomic improvement. Studies suggest they may take five or six injections before they achieve the vast bulk of their improvements.”

He notes

|

that some of the patients in Protocol U had three or four injections within 20 weeks before their enrollment, and then had their next three or four injections in the run-in phase. “It may have taken that long for them to achieve the visual benefit and anatomic benefit,” he adds.

Panelist Judy E. Kim, MD, notes that previous DRCRnet studies have shown that some patients are early, fast responders to treatment, and others are slow responders. “Some may require six or more monthly anti-VEGF injections before we see visual and/or anatomic improvement,” she says.

At month six, the top-line Protocol U results showed no significant difference in visual acuity outcome between the two treatment arms, with mean improvements of 2.7 letters in the combination arm and 3 letters in the mono-therapy arm.

However, anatomic outcomes did appear to differ between the arms, with the combination group having a significantly greater reduction in retinal thickness, with mean central subfield thickness decreases of 110 µm with combination therapy compared to 62 µm with monotherapy. Furthermore, 52 percent vs. 31 percent of patients in the combination vs. monotherapy arms had resolution of DME.

Correlating Anatomic, Visual Acuity Data

Dr. Wykoff asks the panelists how they correlate anatomic data with visual acuity. The consensus is that retinal thickness as a biomarker may not correlate well with visual acuity, although retinal dryness may.

In any study involving steroids, one has to normalize for cataract development, Dr. Ober says. “That certainly can skew the visual acuity data, even when you have equal or better anatomic outcomes,” he says.

In addition, Dr. Ober notes that delayed initiation of the superior treatment regimen, especially

|

with anti-VEGF therapy, can ultimately limit visual acuity potential. “The most pertinent example was in the 36-month results of the RIDE and RISE extension study,”3 he says. “The initially sham-treated group received treatment in the crossover arm after 24 months.” That same group had improvement in both vision and anatomy, but not at the same levels as the initially treated group.

“Identifying patients who are going to be slow responders to anti-VEGF alone is really the trick,” adds Dr. Ober. “I don’t think we have a way to do that yet.”

Looking for New Biomarkers

Dr. Kim notes that multiple studies have shown that retinal thickness on optical coherence tomography correlates poorly with visual acuity. “Perhaps we have to look for other OCT biomarkers that may correlate better with visual acuity,” she says.

Those biomarkers may include the integrity of the outer segment, the external limiting membrane and ellipsoid zone or other factors yet to be determined, she says. “Unlike exudative age-related macular degeneration, it appears that the retina can tolerate some fluid in DME,” Dr. Kim says. “While a dry retina is the goal, many DME eyes had persistent edema, even though vision improved on maximal therapy.”

Adds Michael A. Singer, MD, “We don’t know exactly how OCT fits into visual acuity. There’s definitely a disconnect.” But that begs the question: What’s the difference between visual acuity and visual function? “It’s very hard to measure visual function,” he says. “But when their OCT images show a dry macula, patients say they can do more activities of daily living.”

Adds Dr. Ober, “We do need to look at more just retinal thickness.” He notes that the integrity of the ellipsoid zone and outer photoreceptors is important, “but I would make a counterargument that the potential loss in ellipsoid-zone function may reflect permanent damage from the initial DME.” RS

REFERENCES

1. Bressler NM, Beaulieu WT, Glassman AR, et al; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Persistent macular thickening following intravitreous aflibercept, bevacizumab, or

ranibizumab for central-involved diabetic macular edema with vision impairment: A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:257-269.

2. Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Liu D, et al, for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Effect of adding dexamethasone to continued ranibizumab treatment in patients with persistent diabetic macular edema: A DRCR Network Phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:29-38

3. Phase II combination steroid and anti-VEGF for persistent DME. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01945866. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01945866

4. Wykoff CC, Elman MJ, Regillo CD, Ding B, Lu N, Stoilov I. Predictors of diabetic macular edema treatment frequency with ranibizumab during the open-label extension of the RIDE and RISE Trials. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1716-21.