|

A 75-year-old Caucasian woman presented with three days of symptomatic painless vision loss in the left eye. Her medical history included Alzheimer’s dementia, and her ocular history was unremarkable with a remote, uncomplicated cataract extraction. On review of systems, she denied fevers, rashes, shortness of breath or other systemic symptoms.

Workup and imaging findings

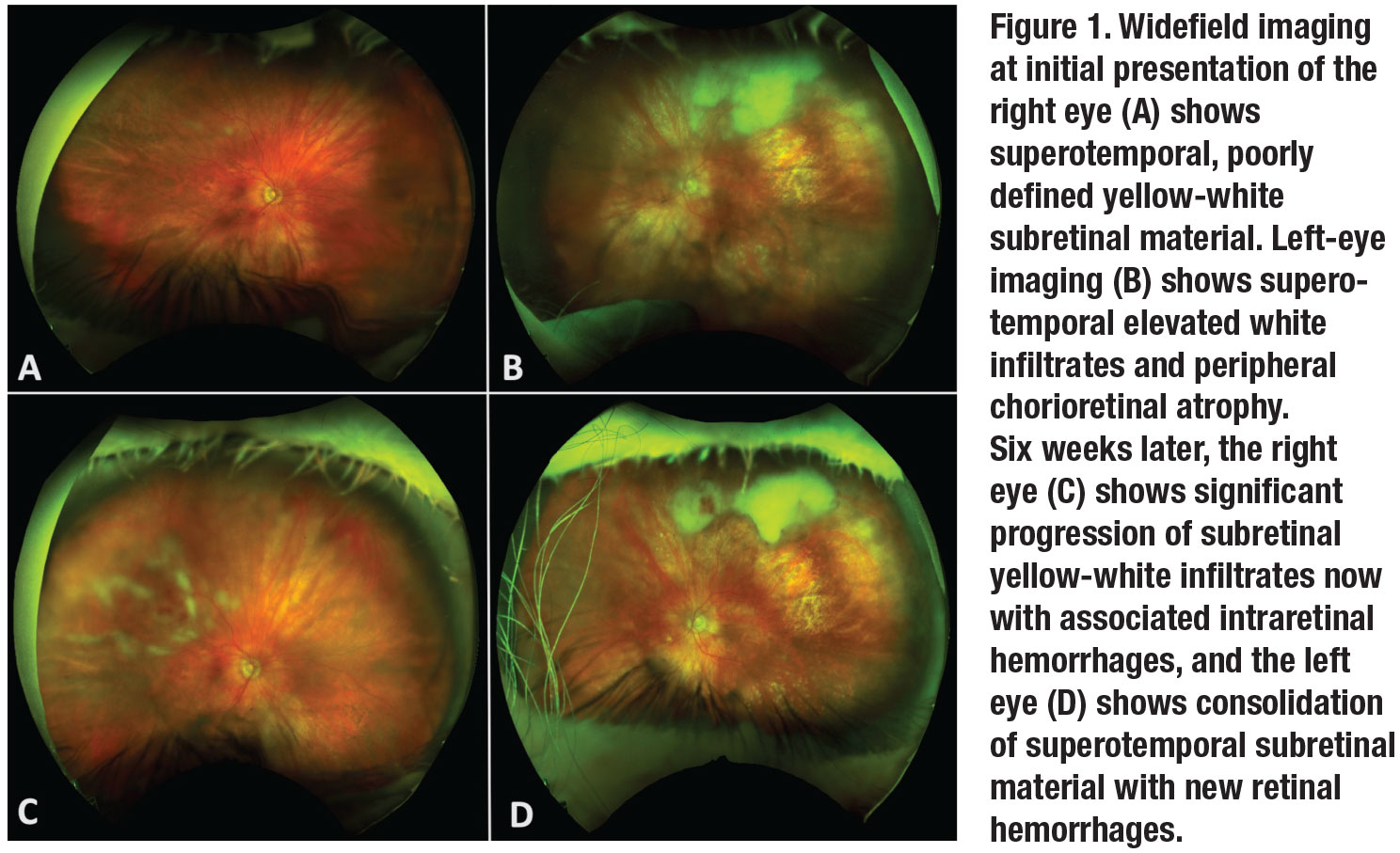

The patient appeared generally healthy, and her vital signs were within normal limits. On ocular examination, visual acuity with correction was 20/25 OD and counting fingers OS. Intraocular pressures were 37 mmHg OD and 44 mmHg OS. Anterior segment examination revealed 2+ cell OD and 3+ cell OS without granulomatous keratic precipitates or hypopyon. Posterior segment examination of the right eye showed 1+ vitreous cell with superotemporal multifocal subretinal yellow-white material and focal nasal vascular sheathing (Figure 1). Posterior evaluation of the left eye showed 2+ vitreous cell with a large collection of subretinal white material superiorly and scattered areas of chorioretinal atrophy.

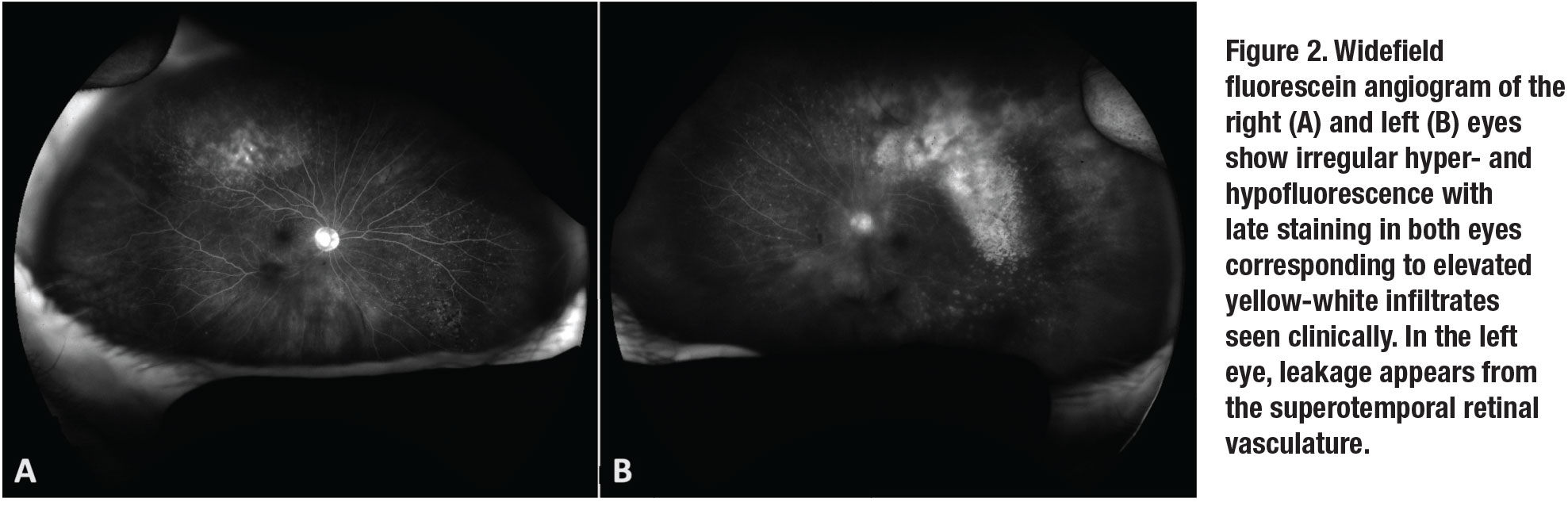

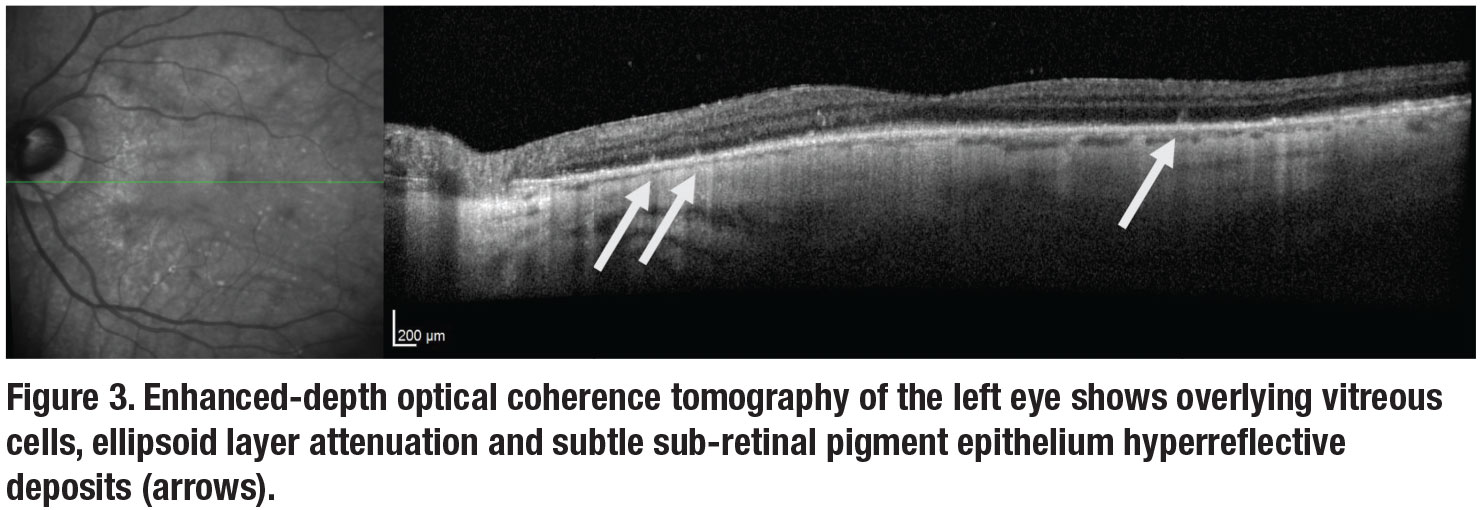

Fluorescein angiography (Figure 2) of both eyes revealed multifocal areas of punctate hyperfluorescence with late staining. Optical coherence tomography of the right eye was unremarkable. In the left eye, OCT demonstrated attenuation of the ellipsoid zone and small multifocal sub-retinal pigment epithelium deposits (Figure 3, page 12).

The differential diagnosis of this patient with bilateral posterior uveitis with retinal or subretinal whitening included infectious, inflammatory and neoplastic etiologies. Infectious causes included bacterial (e.g., tuberculosis, syphilis, Lyme disease), viral (e.g., herpetic necrotizing retinitis), and fungal and protozoan organisms. Inflammatory diseases like sarcoidosis were considered but thought to be less likely. Neoplastic causes such as primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL), secondary spread of systemic lymphoma, and leukemic infiltration were strongly considered.

|

Work-up, diagnosis and treatment

This patient’s anterior uveitis was initially treated with prednisolone acetate 1% every two hours in both eyes. IOP-lowering drops were initiated for ocular hypertension. An anterior chamber paracentesis for the ocular patient care report (PCR) was negative for varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex virus-1 and -2, cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis. Blood work, including Lyme antibody, syphilis serologies, quantiFERON-tuberculosis gold, angiotensin converting enzyme, complete blood count, and a complete metabolic panel returned normal.

One month after her initial presentation, the patient’s IOPs had improved to 14 mmHg OD and 16 mmHg OS, and her visual acuity remained unchanged. Fundoscopic examination revealed progression of the fluffy white infiltrates with associated retinal hemorrhages superotemporally in the right eye with consolidated-appearing fluffy white subretinal material in the left eye.

Given the progression of disease and negative workup, a diagnostic and therapeutic pars plana vitrectomy with subretinal aspiration biopsy was undertaken in the left eye. Histopathologic examination of the vitreous specimen showed rare atypical B-cells in a background of chronic granulomatous vitritis. In contrast, subretinal needle biopsy showed high-grade B-cell lymphoma compatible with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of primary vitreoretinal or primary central nervous system origin.

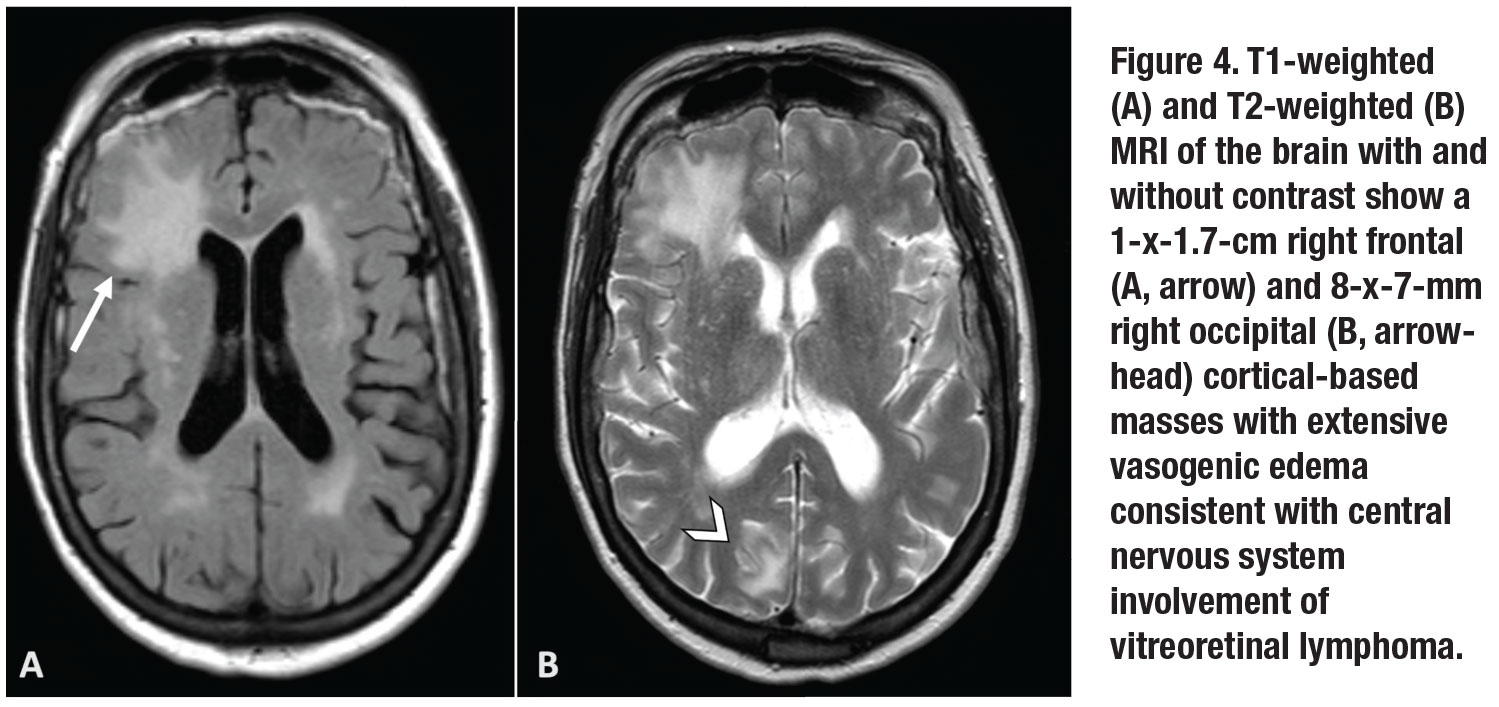

Further PCR testing of the subretinal material demonstrated MYD88 L265P mutation, supporting a diagnosis of vitreoretinal lymphoma. MRI of the brain and orbit revealed a 1-x-1.7-cm right frontal and 8-x-7-mm right occipital cortical-based masses with extensive vasogenic edema (Figure 4, page 13).

|

|

Presentation of disease

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL) is an ocular subset of primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) that initially presents in the eyes. Roughly one third of patients with PCNSL will have manifestation of VRL at the time of CNS diagnosis, while 48 to 92 percent of patients with PVRL will go on to develop CNS manifestations over a mean follow-up of eight to 29 months.1

Both diseases are considered rare extranodal, non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas that are generally diagnosed as a high-grade, diffuse, large B-cell lymphoma. Most cases occur in patients age 50 to 70 years. Immunocompromised status is a major risk factor for PCNSL, especially in young populations, with a steep rise in reported cases from the 1970s to 1990s due in part to the U.S. HIV epidemic.1

Patients frequently present with symptoms of painless decreased visual acuity and floaters, or during a secondary evaluation after they’ve been diagnosed with PCNSL. While the anterior chamber typically shows nonspecific anterior uveitis with non-granulomatous keratic precipitates and variable levels of cell and flare, posterior segment findings include vitreous cells and sub-RPE infiltrates.

Without a history of PCNSL or the characteristic sub-RPE aggregates of lymphoma cells, the disease can be challenging to diagnose. It’s frequently mistaken for a chronic, relapsing inflammatory disorder.

Multimodal imaging can be helpful in characterizing the disease. FA will frequently show diffuse vascular leakage, late hyperfluorescence of sub-RPE lesions, punctate hyperfluorescent window defects and round, hypofluorescent lesions.1 FA in VRL only rarely shows petaloid leakage in the macula, a notable contrast to the cystoid changes that frequently occur in uveitis. The round, hypofluorescent spots surrounded by mottled hyperfluorescence can give the appearance described as a “leopard-spot” pattern.

OCT can show nodular deposits of accumulated lymphomatous cell depositions beneath the RPE, resulting in focal dome-shaped hyperreflective pigment epithelial elevations of medium intensity.2 Fundus autofluorescence shows granular hyper- and hypoautofluorescence thought to be associated with active lymphoma.2,3

|

|

Making the diagnosis

A high degree of suspicion is essential when signs suggestive of VRL present. Because of its similarity to other causes of posterior and intermediate uveitis, steroids are frequently prescribed initially. Because steroids are lymphocytic, signs and symptoms improve initially, but withdrawal of systemic steroids results in relapse of lymphocytic proliferation. To make a definitive diagnosis of VRL, intraocular biopsy with diagnostic vitrectomy confirms the presence of lymphoma.

Submitted specimens should include 1.5 to 2 mL of undiluted vitreous.4 If a subretinal aspirate or chorioretinal biopsy is collected, then the specimen should be promptly delivered to the laboratory for histological and cytopathological analysis. Cytokine analysis may also be ordered and classically shows elevated interleukin 10 (IL-10) levels or an increased IL-10 to IL-6 ratio in PVRL compared to patients with uveitis.5

Recent reports have described molecular genetic testing of aqueous and vitreous samples for the MYD88 L265P mutation in patients with suspected PVRL. MYD88 is found in approximately 80 percent of PVRL, and with the use of droplet digital PCR, aqueous and vitreous testing for the mutation has a sensitivity of 67 and 75 percent, respectively, with essentially 100 percent specificity.6,7

|

|

Treatments

Available treatments for VRL include systemic chemotherapy, external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) and intravitreal chemotherapy. In cases of bilateral eye involvement or combined ocular and CNS disease, systemic chemotherapy is frequently undertaken in conjunction with a medical oncologist. The most common chemotherapies include high-dose intravenous methotrexate and cytarabine.1

When the disease is restricted to the eye, local treatment, including EBRT or intravitreal chemotherapy, can be effective at inducing local remission and is similarly efficacious to systemic therapy in preventing recurrence.8 EBRT is highly effective, but its use must be weighed against the risk of local complications such as dry eye, cataract formation and radiation retinopathy.

Intravitreal injections of chemotherapy including methotrexate and melphalan have demonstrated local control of VRL over extended treatment protocols. Intravitreal rituximab has also been evaluated, but with higher relapse rates than other agents.9 All intravitreal injection-based protocols involve repetitive injections and the associated risk of ocular complications.

Bottom line

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma is a rare and potentially fatal extranodal lymphoma that can present multiple diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Due to its potential to involve the CNS and for delayed diagnosis due to non-specific findings, a high degree of suspicion must be maintained based on the clinical signs and patient demographics. Multimodal imaging can aid in the diagnosis of this challenging disease, but definitive diagnosis is made with intraocular biopsy. Treatment includes local and systemic therapies depending on the overall state of the disease, with VRL restricted to the eye frequently receiving injections of chemotherapy or EBRT. RS

REFERENCES

1. Sagoo MS, Mehta H, Swampillai AJ, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59:503-516.

2. Egawa M, Mitamura Y, Hayashi Y, Naito T. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomographic and fundus autofluorescence findings in eyes with primary intraocular lymphoma. Clin Ophthalmol Auckl NZ. 2014;8:335-341.

3. Casady M, Faia L, Nazemzadeh M, Nussenblatt R, Chan C-C, Sen HN. Fundus autofluorescence patterns in primary intraocular lymphoma. Retina. 2014;34:366-372.

4. Pulido JS, Johnston PB, Nowakowski GS, Castellino A, Raja H. The diagnosis and treatment of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: A review. Int J Retina Vitr. 2018;4:18.

5. Pochat-Cotilloux C, Bienvenu J, Nguyen A-M, et al. Use of a threshold of interleukin-10 and il-10/il-6 ratio in ocular samples for the screening of vitreoretinal lymphoma. Retina. 2018;38:773-781.

6. Hiemcke-Jiwa LS, Ten Dam-van Loon NH, Leguit RJ, et al. Potential diagnosis of vitreoretinal lymphoma by detection of MYD88 mutation in aqueous humor with ultrasensitive droplet digital polymerase chain reaction. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:1098-1104.

7. Raja H, Salomão DR, Viswanatha DS, Pulido JS. Prevalence of MYD88 L265P mutation in histologically proven, diffuse large b-cell vitreoretinal lymphoma. Retina. 2016;36:624-628.

8. Grimm SA, Pulido JS, Jahnke K, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma: An International Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Collaborative Group Report. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2007;18:1851-1855.

9. Larkin KL, Saboo US, Comer GM, et al. Use of intravitreal rituximab for treatment of vitreoretinal lymphoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:99-103.