Take-home Points

|

|

|

Bio Dr. Modjtahedi is the director of the Eye Monitoring Center (Kaiser Permanente Southern California) and clinical associate professor at the Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, California. |

One of the aspects of being a retina specialist that attracted many of us to this field was the ability to stay connected to patients’ systemic conditions. Usually this takes the form of managing the retinal complications of systemic disease. However, emerging research increasingly suggests that the retina may hold promise in the evaluation and management of extraocular conditions.

We have the opportunity to form long-term relationships with our patients, and part of that entails seeing their general health evolve. Among people with diabetes, for example, it’s not unusual for us to witness the progression of their diabetic disease over the years. Frequently, patients who may seem outwardly fine but whose retinas demonstrate advanced retinopathy will deteriorate clinically. Their retinal status is clearly a harbinger of things to come. Within a few years these patients are often on dialysis or suffer significant macrovascular events such as myocardial infarctions or cerebrovascular accidents.

The question then becomes, what role can we as retina specialists play in the broader medical management of our patients? This has been an area of considerable interest for many years, with research having focused on the relationship between retinal status and several conditions including cardiovascular, renal and cerebrovascular diseases, and Alzheimer’s disease.1-4

Stratifying heart disease risk

Using retinal images to stratify systemic vascular disease risk is appealing because it has been well established that aggressive medical management in high-risk patients can substantially reduce their risk of MI and CVA. There’s a strong scientific rationale for using retinal images for vascular disease stratification since the retina is the only place where blood vessels can be visualized directly.

|

We additionally know histologic similarities exist between the retina and brain, given their shared embryotic origin.3 Some authors, such as Jack W.R. Brownrigg, MRCS, and colleagues in the United Kingdom, have found that accounting for microvascular complications of diabetes would cause 20 percent of diabetes patients to move into a different cardiovascular risk category.5

Several risk calculators have been used to determine the future risk of cardiovascular disease and help guide management decisions, such as when to start aspirin or statin therapy.

One such commonly used tool is the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease calculator.6 It uses age, gender, race, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, history of diabetes, smoking status, hypertension treatment, statin use and aspirin use to provide a 10-year risk estimate for patients. Although these risk calculators provide important insights into disease management, their real-world performance can sometimes be lacking because they may miscalculate true risk.7

DR as a biomarker of systemic vascular disease

Using the retina as a window into a patient’s cardio- and cerebrovascular disease status is attractive because it is relatively easy to view, especially when compared to other tools such as cardiac calcium scores.

Several studies have evaluated whether diabetic retinopathy was independently associated with cardiovascular outcomes, but they produced mixed results. The cause of these conflicting findings are multifactorial and relate to how the studies measured outcomes, length of follow-up, covariates and cohort size.

Additionally, many studies categorized patients simply as retinopathy vs. no retinopathy, which may not have provided enough granular detail to find important associations. With this in mind, we attempted to answer some of the questions around whether diabetic retinopathy is an independent risk factor for systemic vascular disease.1

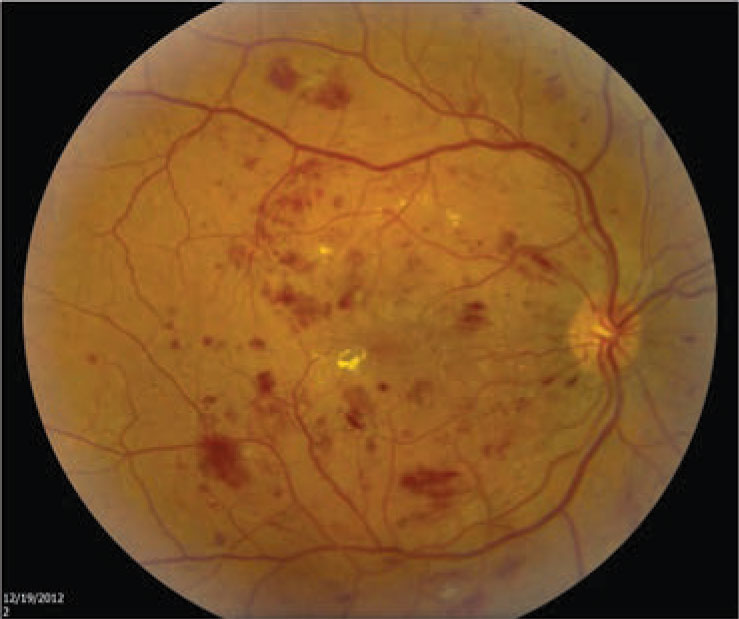

Figure 1. Moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, shown here with macular edema, was found to carry a 92 percent greater risk for myocardial infarction and a 90 percent greater risk for development of congestive heart failure. (Courtesy Nidhi Relhan Batra, MD) |

Quantifying vascular disease risk

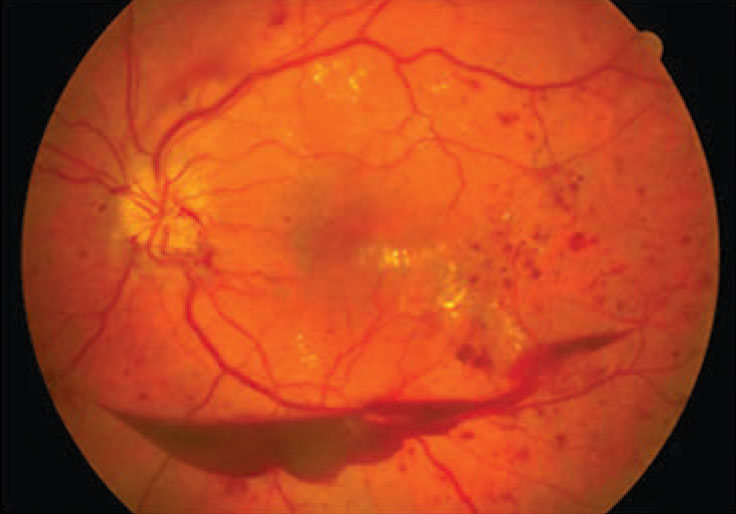

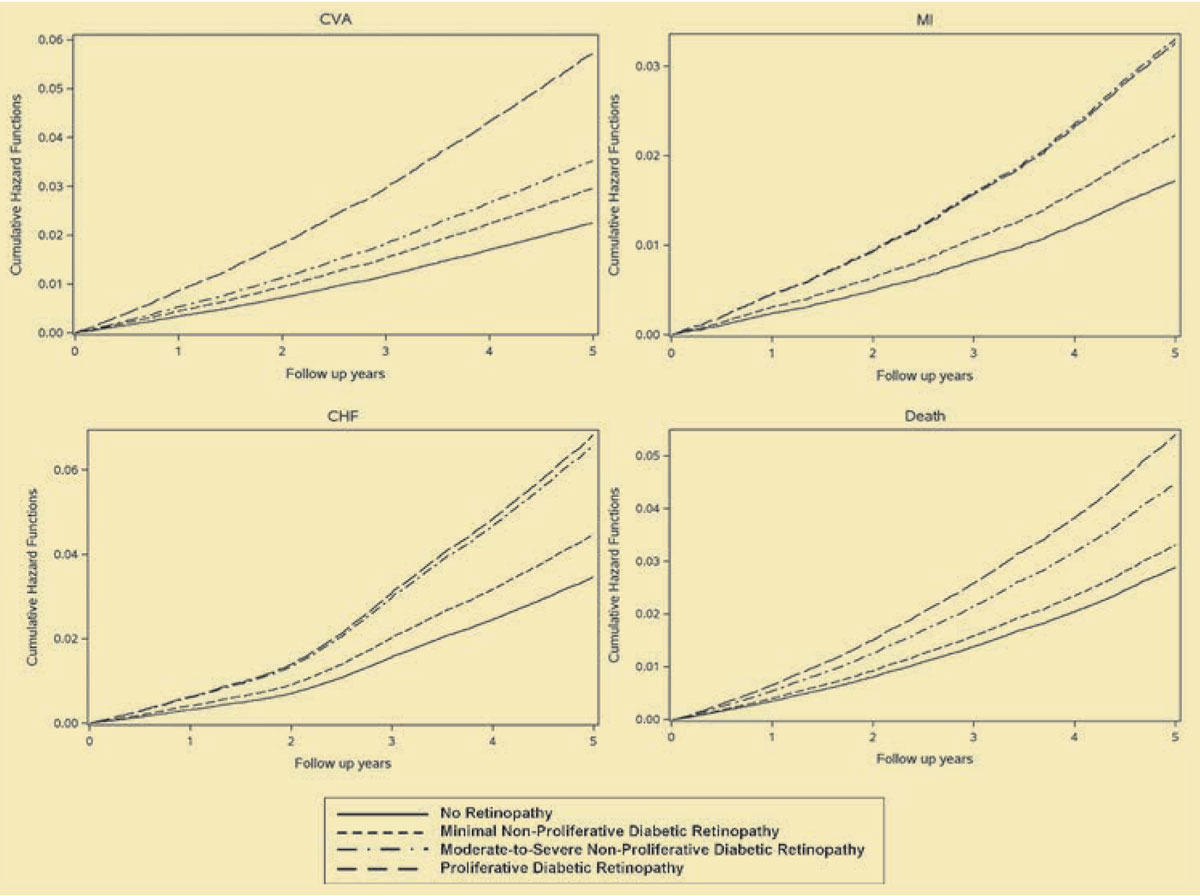

Our study analyzed the five-year outcomes of patients who received DR screening in our telemedicine program. We graded retinopathy severity based on 45-degree fundus photos, with the highest degree of retinopathy between the two eyes chosen for analysis. We divided severity into four categories: no retinopathy; minimal nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; moderate-to-severe NPDR (Figure 1); and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (Figure 2,).

We then calculated the five-year risk of new MI, congestive heart failure (CHF), CVA and all-cause mortality after adjusting for key cardiovascular and diabetes risk factors that included gender, age, race or ethnicity, diabetes duration, hemoglobin A1c, LDL and HDL levels, tobacco use, history of hypertension, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, body-mass index, statin use, estimated glomerular filtration rate and urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio.

We were able to use a large real-world population that allowed for sufficient statistical power to detect differences between groups (n=77,376). The results showed that even after accounting for the aforementioned covariates, DR severity was significantly associated with the risk of all the outcomes considered, with higher degrees of retinopathy appearing to carry an increased risk for each outcome.

|

| Figure 2. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy, shown here with a preretinal hemorrhage, was found to carry an 89 percent greater risk for myocardial infarction and a 253 percent higher risk for cerebrovascular accident. (Courtesy Nidhi Relhan Batra, MD) |

The increased risk of each outcome with increasing retinopathy severity was especially noteworthy. When comparing patients with DR and those with no retinopathy, we observed the following relationships in terms of hazard ratio and range:

Minimal NPDR: MI (HR, 1.30; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15-1.46); CHF (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.19-1.40); CVA (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.18-1.46); and all-cause mortality (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.05-1.25).

Moderate-to-severe NPDR: MI (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.57-2.34); CHF (HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.66-2.18); CVA (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.29-1.89); and all-cause mortality (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.32-1.82).

PDR: MI (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.26-2.83); CHF (HR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.47-2.59); CVA (HR, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.84-3.48); and all-cause mortality (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.36-2.56).

These results point to a striking trend, as illustrated in Figure 3. For example, a patient with PDR has a 253 percent higher risk for a CVA in the next five years than a person with diabetes but without retinopathy, even after controlling for risk factors such as HbA1c or blood pressure.

Importantly the patients who participated in this study were part of a DR screening program and typically not already under the care of an ophthalmologist. As a result, the number of patients with more advanced forms of severe retinopathy, who were by extension also generally “sicker,” were under-represented in this cohort. This may have ultimately resulted in an underestimation of systemic disease risk in patients with higher degrees of retinopathy.

|

| Figure 3. Cumulative hazard functions for cerebrovascular accident (CVA), myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF) and all-cause mortality by diabetic retinopathy status. These results show that diabetes patients with moderate-to-severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy and proliferative DR are at significantly higher risk for a cardiovascular event than diabetes counterparts with no retinopathy or minimal NPDR. (Reprinted with permission Ophthalmology1) . Click image to enlarge. |

In line with clinical experience

These findings are consistent with many of our clinical experiences. I’ve had many patients whose lab values seemed at target goals, but whose retinas showed significant retinopathy. These patients ultimately suffered a MI or CVA within a few years of establishing care with me. The reason for this may be that the retina provides a more holistic view of a patient’s vascular disease burden.

While current risk calculators are limited in the number of variables they can consider and are typically constrained to the most recent set of values, the retina may provide us with a view of the aggregate damage to the vascular system over years—including prior years of worse diabetes control—and provide a superior biomarker for future disease.

Potential for technology, AI

Several advances in technology may provide even more insights. Greater retinal visualization with widefield viewing systems and more detailed visualization of the retinal vasculature with optical coherence tomography angiography allow for better characterization of retinal changes.

Artificial intelligence/machine learning may hold promise in using retinal information for risk stratification. Subtle retinal changes may be easier to quantify using AI which may also allow for more detailed analysis than is practical by a human grader.

While human grading is currently limited to traditional classification schemes (such as microaneurysm and dot-blot hemorrhages), AI-based solutions may find new markers of systemic disease that we humans may not even be considering.

Tyler Hyungtaek Rim, MD, and colleagues in Singapore and South Korea recently demonstrated that a deep-learning-based analysis of retinal images was comparable to CT-scan measured cardiac calcium score in predicting cardiovascular events.8

|

Bottom line

I think the findings of our publication are noteworthy because they demonstrated such a strong relationship existed even when using “limited” retinal evaluation (two 45 degree photographs per eye without the use of widefield photographs or angiography) and “primitive” grading schemes (human-graded degree of retinopathy as opposed to an AI-based solution). This gives us hope that more advanced imaging and interpretation schemes may undercover even more powerful relationships.

In the future we may use the retina like a vital sign that helps optimize the medical management of our patients for a host of diseases, not only systemic vascular disease. RS

REFERENCES

1. Modjtahedi BS, Wu J, Luong TQ, Gandhi NK, Fong DS, Chen W. Severity of diabetic retinopathy and the risk of future cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:1169-1179.

2. Poplin R, Varadarajan AV, Blumer K, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular risk factors from retinal fundus photographs via deep learning. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2:158-164.

3. Lee CS, Apte RS. Retinal biomarkers of Alzheimer disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;218:337-341.

4. Ranchod TM. Systemic retinal biomarkers. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021;32:439-444.

5. Brownrigg JR, Hughes CO, Burleigh D, et al. Microvascular disease and risk of cardiovascular events among individuals with type 2 diabetes: A population-level cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:588-597.

6. ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus. American College of Cardiology. Available at: https://tools.acc.org/ascvd-risk-estimator-plus/#!/calculate/estimate. Accessed September 2, 2021.

7. Yadlowsky S, Hayward RA, Sussman JB, McClelland RL, Min YI, Basu S. Clinical implications of revised pooled cohort equations for estimating atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:20-29.

8. Rim TH, Lee CJ, Tham YC, et al. Deep-learning-based cardiovascular risk stratification using coronary artery calcium scores predicted from retinal photographs. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3:e306-e316.