|

Bios Dr. McKay is a retina fellow the University of Washington. Dr. Leveque is a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Washington. Dr. Olmos de Koo is an associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Washington. DISCLOSURES: The authors have no relevant financial disclosures. |

A 65-year-old male was referred to our tertiary care institution for intraocular inflammation of the right eye that didn’t respond to topical steroids.

His ocular history was notable for a zone 1 and 2 open-globe injury of the left eye secondary to penetrating trauma from a metal screw several years earlier. After the open-globe injury was primarily repaired, he developed a retinal detachment that became recurrent with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. That required two additional surgeries for repair, including scleral buckle placement, pars plana vitrectomy with lensectomy and silicone oil tamponade.

His retinal detachment repair was ultimately successful with the injured left eye attaining 20/100 visual acuity.

At the time of his presentation, he was applying topical prednisolone four times daily in the right eye and twice daily in the left eye. He had not recently traveled outside of the United States.

Examination and imaging findings

His examination was notable for visual acuity of 20/20-2 in the right eye and no light perception in the left eye. Intraocular pressures were within normal limits in each eye. His right pupil was reactive, and his left pupil was 7 mm and fixed with a positive afferent pupillary defect by reverse.

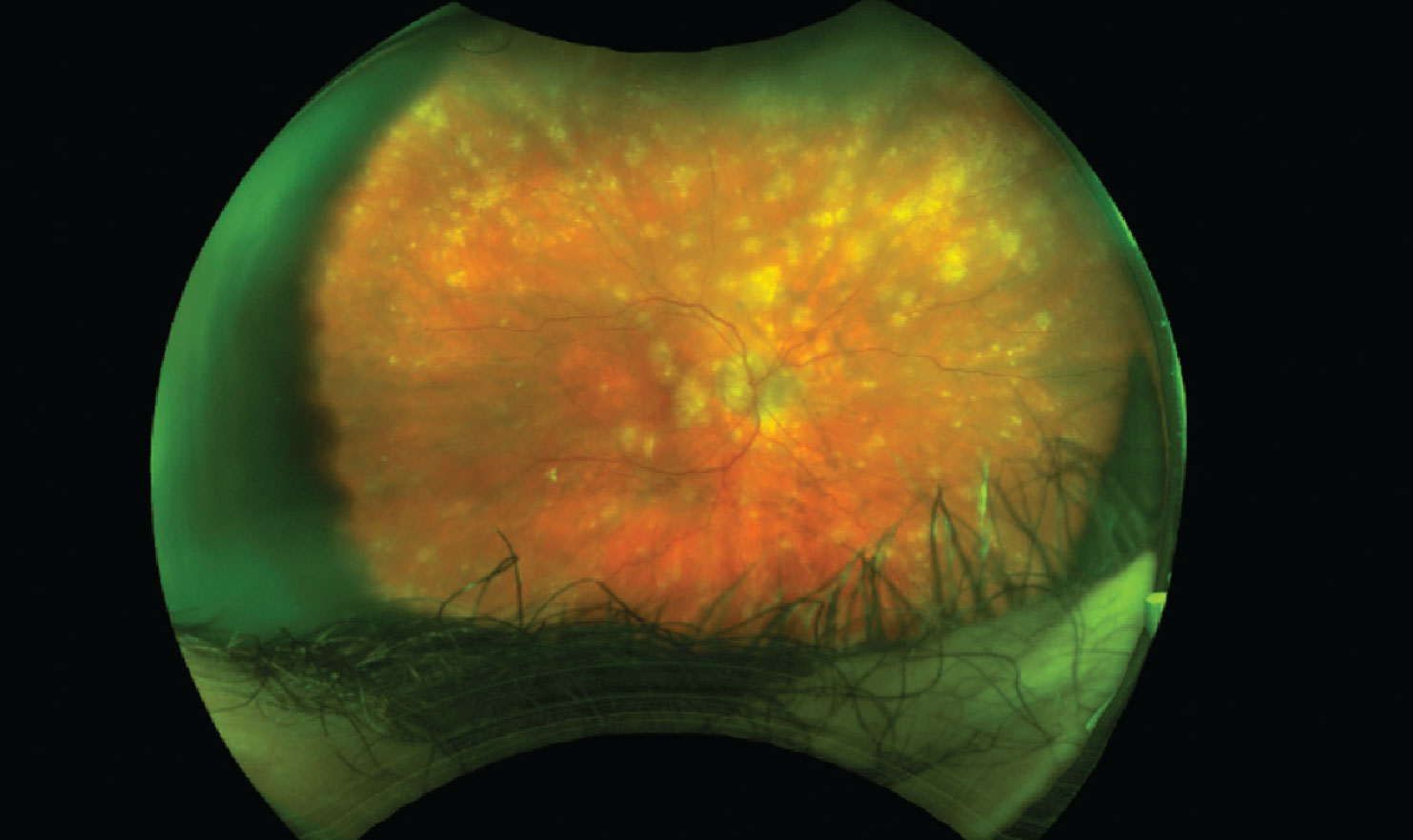

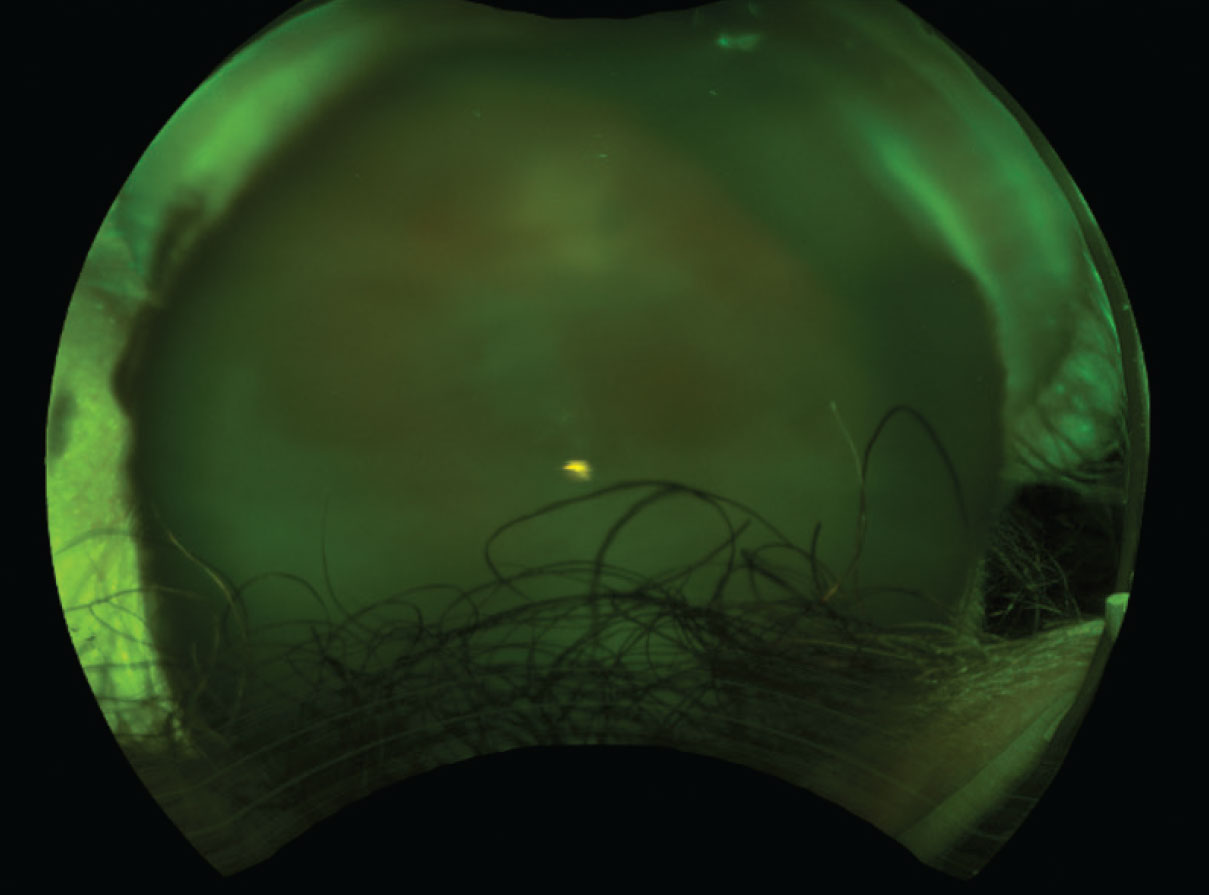

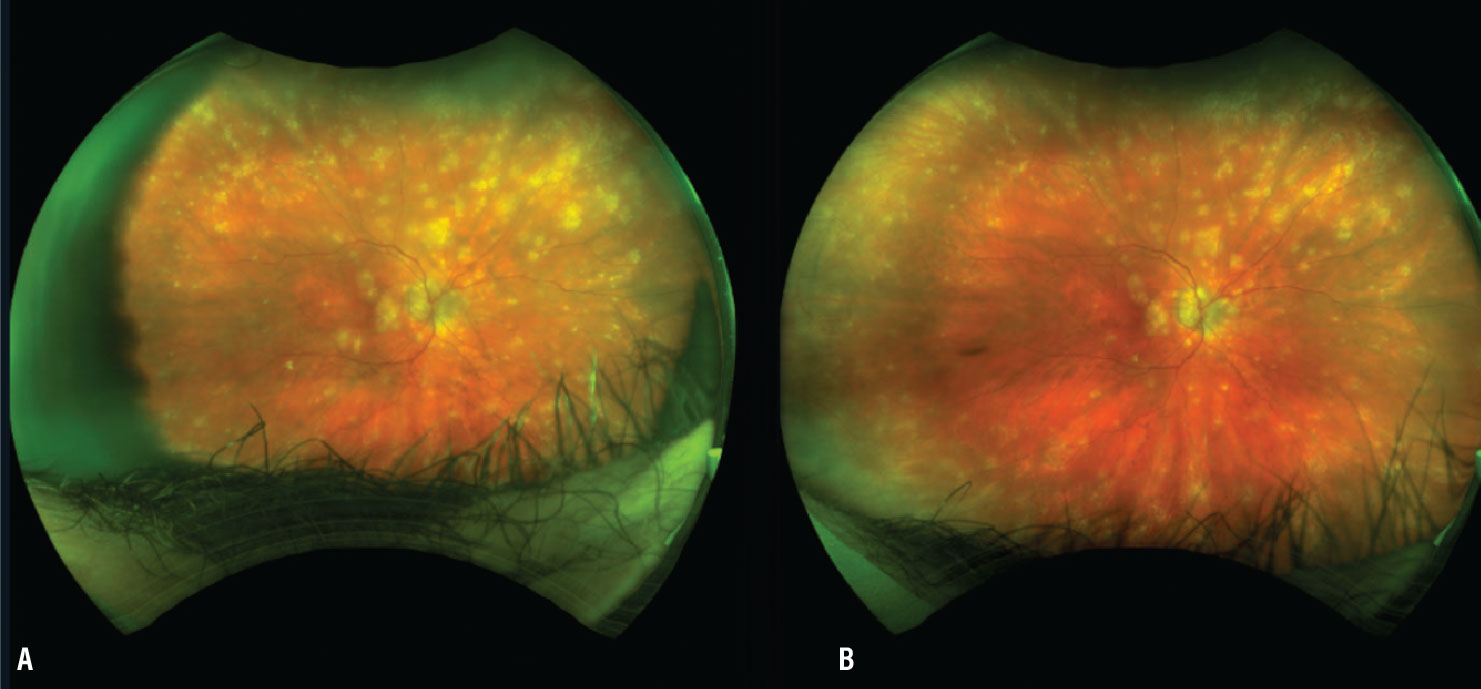

Slit lamp exam of the right eye was notable for 1+ flare in the anterior chamber and 2-3+ vitreous cell. The fundus exam showed multifocal yellow subretinal lesions (Figure 1). The left eye conjunctiva was injected, and the view into the anterior chamber and fundus was limited secondary to dense corneal neovascularization, diffuse stromal edema and corneal scarring. The vitreous was replaced by silicone oil, precluding effective ultrasonography (Figure 2).

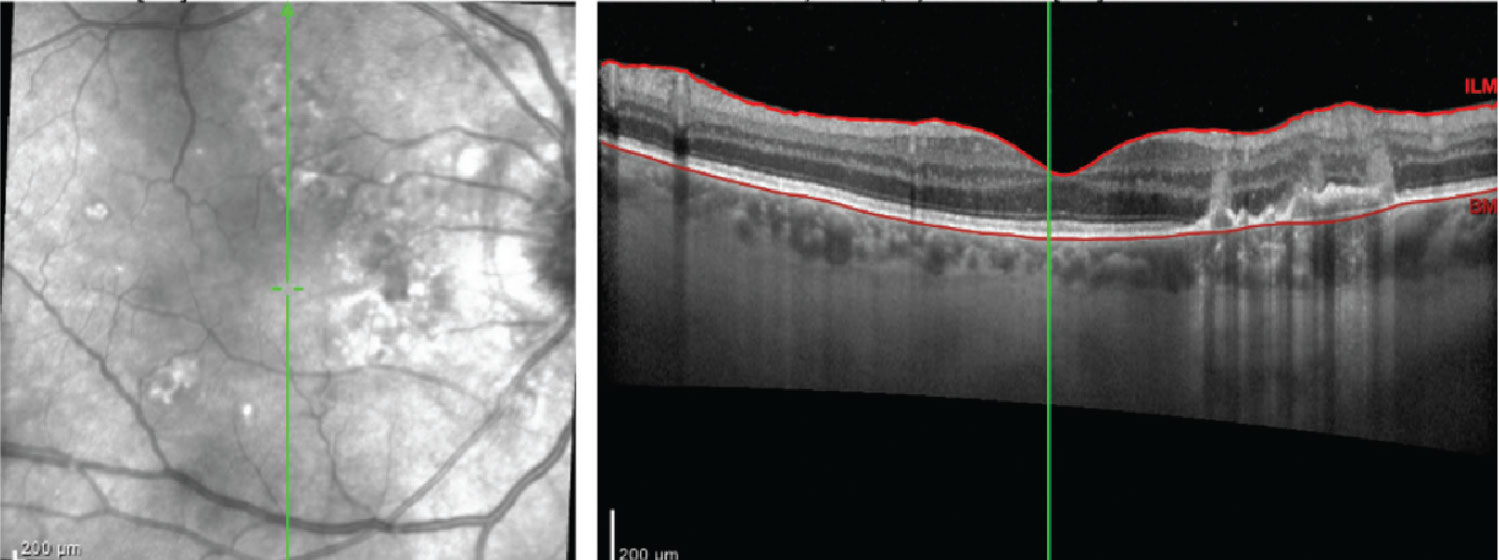

Optical coherence tomography of the right eye showed multiple focal and confluent retinal pigment epithelium elevations in a dome shape (Figure 3).

Work-up

Laboratory work-up included the following tests: syphilis immunoglobulin G and IgM, which was negative; QuantiFERON gold tuberculosis test, also negative; complete blood count (normal); and comprehensive metabolic panel (also normal). A computed tomography lung scan showed no pulmonary nodules.

|

|

Figure 1. Mild media opacity and multifocal yellow subretinal lesions present at the initial presentation. Visual acuity was 20/20-2. |

|

|

Figure 2. Dense vitreous opacities in the left eye at the initial presentation caused this poor view of the fundus findings. Visual acuity was no light perception. |

Diagnosis and management

We diagnosed sympathetic ophthalmia and initiated maximum medical therapy to preserve vision in the patient’s only seeing eye. That included oral prednisone 60 mg daily and methotrexate 25 mg weekly. Initially, he received adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) every other week.

However, we eventually transitioned him to high-dose infliximab (Remicade, Janssen) because of frequent flares and an inability to fully taper the oral prednisone. We used frequent dexamethasone intravitreal injections for recurrent cystoid macular edema. Ultimately, the inflammation was brought under control (Figure 4).

Disease process

Sympathetic ophthalmia (SO) is a rare disease with a reported incidence of 0.1 to 0.5 percent and 19 percent after open-globe injury.1 SO can occur after penetrating and nonpenetrating trauma, as well as intraocular surgery. Pars plana vitrectomy is reported as the most common cause of postsurgical sympathetic ophthalmia.2–4 Presentation may be days to years after the trauma or insult, with 90 percent of cases occurring within one year.3

Clinically SO is a bilateral granulomatous panuveitis involving any part of the uveal tract. Hallmarks of SO in the posterior segment are yellow subretinal Dalen-Fuchs nodules (clusters of epithelioid cells containing pigment lying between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane), and/or multiple exudative detachments. Macular edema and choroidal neovascularization may complicate the disease process.5,6

|

|

Figure 3. Optical coherence tomography imaging of the right eye at time of initial presentation shows multiple focal and confluent retinal pigment epithelium elevations in a dome shape. |

|

|

Figure 4. A) The patient’s right eye at the initial presentation before starting medical therapy. B) The same eye following one year of therapy. Note the improvement in vitreous haze and decrease in subretinal yellow lesions. |

Pathophysiology

|

The eye with penetrating trauma or surgery is the exciting eye and the contralateral eye is the sympathetic eye.1–3,6 When trauma or surgery occurs, previously sequestered uveal tissue antigens become exposed to the subconjunctival space where they’re presented via lymphatics to CD4+ helper T-cells in peripheral lymph nodes and the spleen.1–6 As a result, helper CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells travel to both eyes, creating a local granulomatous immune response. Studies suggest a genetic disposition though the human leukocyte antigen, including HLA-DRB1*4 and HLA-DQB1*046.

Treatment options

Oral corticosteroids at 1 mg/kg and systemic immunosuppressive agents are the first-line therapy for SO.1–6 Its severity and chronicity make it one of the few indications for which immunomodulatory therapy should be started at the initial presentation.

Many cases require antimetabolites and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha agents for control and to prevent long-term steroid use. Anti-VEGF agents may be indicated for SO-associated choroidal neovascular membranes. Adjuvant local steroids may be used for residual inflammation or cystoid edema.1–9

Bottom line

Sympathetic ophthalmia is a serious, potentially sight-threatening bilateral panuveitis that follows penetrating injury or an intraocular surgery. Consider SO in cases of bilateral inflammation following PPV or open globe injury. Early treatment with immunomodulatory therapy can help control recalcitrant disease. RS

REFERENCES

1. Bonnie He, Stuti M. Tanya, Chao Wang, Abbas Kezouh, Nurhan Torun, Edsel Ing. The incidence of sympathetic ophthalmia after trauma: A meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;234:117–125.

2. Arevalo JF, Garcia RA, Al-Dhibi HA, Sanchez JG, Suarez-Tata L. Update on sympathetic ophthalmia. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:13–21.

3. Parchand S, Agrawal D, Ayyadurai N, et al. Sympathetic ophthalmia: A comprehensive update. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:1931-1944.

4. Gass JD. Sympathetic ophthalmia following v vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:552–558.

5. Davis JL, Mittal KK, Freidlin V, et al. HLA associations and ancestry in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and sympathetic ophthalmia. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1137–1142.

6. Castiblanco CP, Adelman RA. Sympathetic ophthalmia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:289–302.

7. Galor A, Davis JL, Flynn HW, et al. Sympathetic ophthalmia: incidence of ocular complications and vision loss in the sympathizing eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:704–710.e2.

8. Payal AR, Foster CS. Long-term drug-free remission and visual outcomes in sympathetic ophthalmia. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2017;25:190–195.

9. Paulbuddhe V, Addya S, Gurnani B, Singh D, Tripathy K, Chawla R. Sympathetic ophthalmia: Where do we currently stand on treatment strategies? Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:4201-4218.