|

|

|

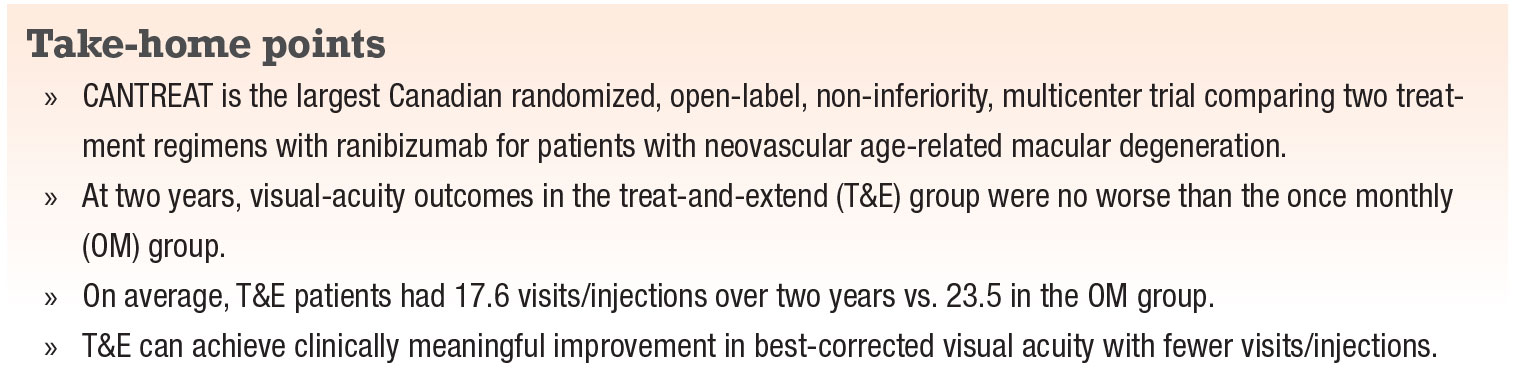

Neovascular age-related macular degeneration is a devastating cause of vision loss, especially in developed nations with an aging population. Although no definitive “cure” exists, anti-VEGF agents have revolutionized the disease outlook for our patients. Yet, many challenges persist. They’ve become more acute during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The burden of frequent visits and injections as well as treatment cost are major hurdles to timely, consistent care. To overcome them, some retina specialists follow a pro re nata and/or a treat-and-extent (T&E) strategy. The ultimate goal of these strategies is multi-faceted:

- to minimize disease activity;

- maintain or improve visual acuity; and

- minimize the number of injections.

Here, we report on the Canadian Treat-and-Extend Analysis Trial with Ranibizumab (CANTREAT) that provides evidence supporting less frequent injections, which can be valuable as we try to minimize patient visits during the pandemic.

Goal of CANTREAT

|

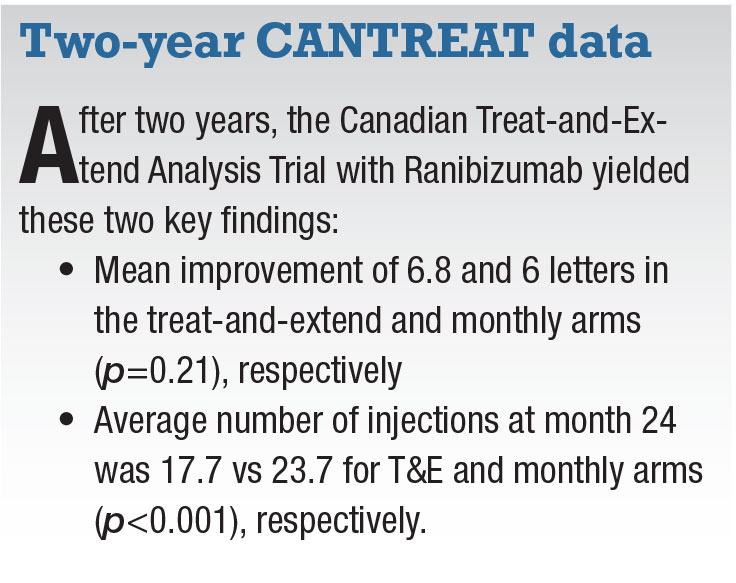

CANTREAT is a two-year randomized non-inferiority trial designed to compare the efficacy of administering ranibizumab (Lucentis, Novartis in Canada; Roche/Genentech) in a once-monthly (OM) vs. T&E approach across 27 Canadian centers.1,2

Only two other trials, TREX and TREND, have prospectively compared the two regimens. However, TREX registered only 60 patients and had many missing data points after two years. TREND did not continue beyond one year.3.4

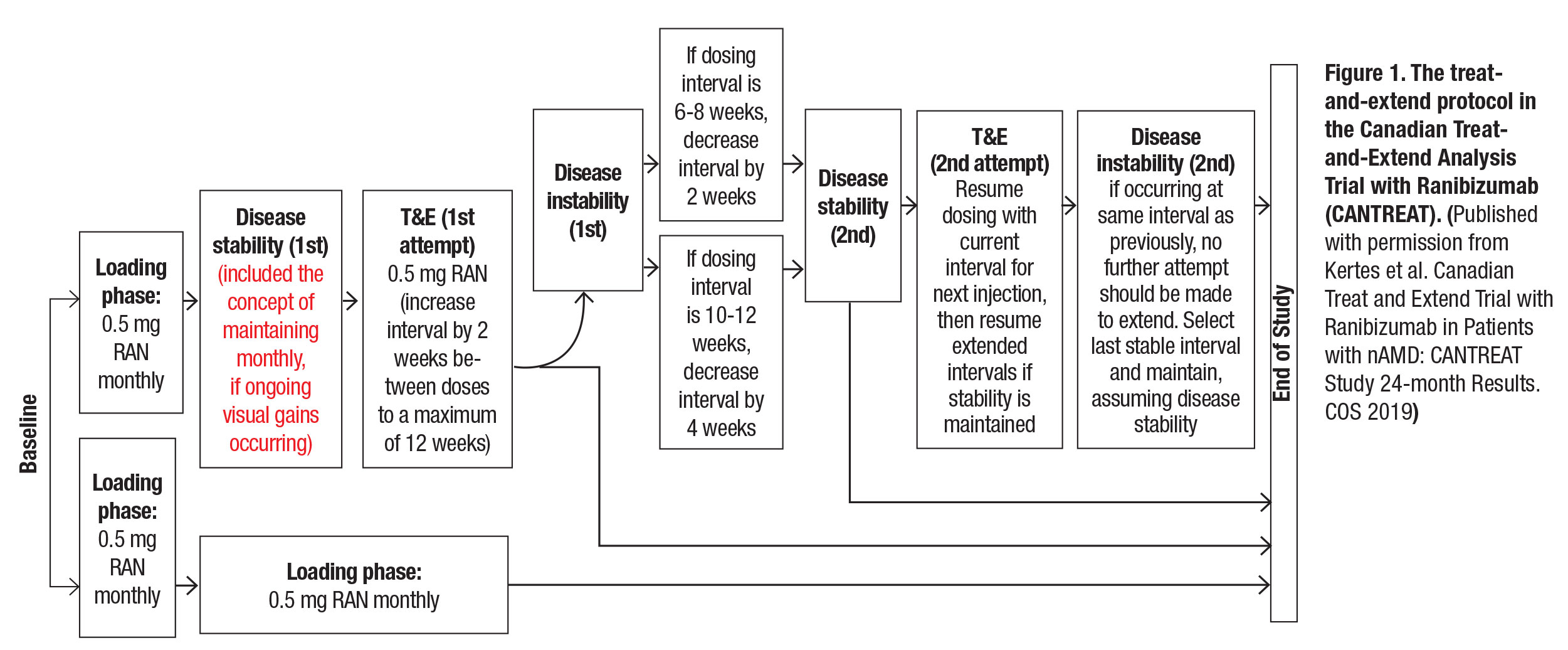

CANTREAT randomized treatment-naive patients to monthly or T&E treatment following an initial loading phase of three consecutive monthly intravitreal ranibizumab 0.5 mg injections (Figure 1). At baseline, all patients had a standard ophthalmic examination, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) best-corrected visual acuity measurements and optical coherence tomography. OM patients also had monthly exams along with ETDRS BCVA measurements and OCT testing every three months. T&E patients received all diagnostic testing at each clinic visit. All patients had intravenous fluorescein angiography at baseline and at weeks 52 and 104

A total of 580 patients were enrolled (T&E=287, OM=293), approximately 80 percent of whom completed the 24-month follow-up. Primary outcomes were to determine whether mean change in BCVA from baseline to month 12 with T&E was non-inferior to monthly treatment and the number of injections it took to achieve those outcomes. Secondary outcomes were:

- Duration of treatment-free intervals.

- Percent of patients with a gain/loss of ≥5, ≥10, ≥15 ETDRS letters from baseline at 12 and 24 months.

- Mean change in BCVA at 24 vs. three months.

- Mean change in BCVA from baseline to month 24.

- Number of injections from baseline to month 24.

- Number of injections at months 12 and 24.

|

Compared with PRN dosing

Other than the TREX and TREND studies, the CANTREAT results can also be compared with PRN dosing in two other large clinical trials, CATT5 and IVAN.6 These studies reported PRN dosing to be no worse compared to monthly treatment, with a fewer number of injections through year two in the CATT trial in the PRN group. Similarly, HARBOR7 demonstrated that PRN dosing of ranibizumab could achieve clinically meaningful BCVA improvements, even though it failed to meet non-inferiority endpoints compared to monthly injections.

While many of us have been treating patients on a T&E regimen, CANTREAT provides Level 1 evidence for non-inferiority of this approach to monthly injections. At month 24, 73.7 percent of patients in CANTREAT were able to extend the treatment interval to eight or more weeks and 43.1 percent to 12 weeks. Certainly, the significantly fewer number of injections T&E management affords minimizes the burden and cost of care without compromising VA outcomes.

Tailoring treatment to patient needs

It should be emphasized that a T&E approach is tailored to every patient’s needs. While some patients remain stable on a 12-week or longer injection interval, a significant proportion need monthly injections. These patients may still have good visual outcomes and should not be considered treatment failures. The goal is to stay ahead of disease activity and carefully increase intervals but only when it’s possible and reasonable.

We should note that many CANTREAT patients whom we could not extend beyond six weeks (i.e., 26.2 percent by 24 months) ultimately did very well in terms of VA outcomes. In fact, BCVA improvement was similar between this cohort and those extended up to 12 weeks. We didn’t find any correlation with interval extension and baseline characteristics such as age, central retinal thickness and subretinal fluid.

In CANTREAT, we didn’t tolerate any subretinal fluid when deciding on interval extension. However, with current new evidence suggesting subretinal fluid can be tolerated without compromising outcomes,8 it’s plausible that these patients could tolerate longer treatment intervals.

Tailoring treatment to patient needs also means keeping in mind the patient’s comfort with more frequent injections, travel distance and level of understanding regarding the T&E philosophy. It’s important to keep in mind that visual outcomes, not treatment interval or OCT findings, determine treatment success.

A cohort of CANTREAT patients have also been extended to three years. The three-year data have helped us understand long-term outcomes of nAMD patients treated with the T&E regimen in terms of VA, number of injections, geographic atrophy, intraocular pressure and characteristics that may help identify who may require fewer or more injections. RS

REFERENCES

1. Kertes PJ, Galic IJ, Greve M, et al. Efficacy of a treat-and-extend regimen with ranibizumab in patients with neovascular age-related macular disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:244-250.

2. Kertes PJ, Galic IJ, Greve M, et al. Canadian treat and extend analysis trial with ranibizumab in patients with neovascular age-related macular disease: 1-Year results of the randomized CANTREAT study. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:841-848.

3. Wykoff CC, Croft DE, Brown DM, et al, for TREX-AMD Study Group.. Prospective trial of treat-and-extend versus monthly dosing for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: TREX-AMD 1-year results. Ophthalmology. 2015;122: 2514–2522.

4. Silva R, Berta A, Larsen M, Macfadden W, Feller C, Mones J, for the TREND Study Group. Treat-and-extend versus monthly regimen in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Results with ranibizumab from the TREND study. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:57–65.

5. Martin DF, Maguire MG, Fine SL, et al. (Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group). Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Two-year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1388-1398.

6. Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, et al. A randomised controlled trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alternative treatments to Inhibit VEGF in Age-related choroidal Neovascularisation (IVAN). Health Technol Assess. 2015;19:1-298.

7. Ho AC, Busbee BG2, Regillo CD, et al. Twenty-four-month efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2014; 121: 2181-2192.

8. Guymer RH, Markey CM, Mcallister IL, et al. Tolerating subretinal fluid in neovascular age-related macular degeneration treated with ranibizumab using a treat-and-extend regimen: FLUID study 24-month results. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:723-734.