|

When it comes to appropriately diagnosing and managing complex ocular inflammatory disease, a healthy understanding of potential etiologies and how to formulate a differential diagnosis are of paramount importance. A focused workup removes hurdles on the way to disease treatment and, ultimately, quiescence.

I find too frequently that when evaluating patients with uveitis, physicians, both ophthalmologists and non-ophthalmologists alike, tend to order extraneous and unnecessary testing. Here, I’ll explore a targeted approach to lab testing and review what tests should and shouldn’t be ordered.

Three goals of lab testing

In my opinion, lab testing has three goals:

- Ensure we don’t miss a systemic infection, and simultaneously “clear the way” for regional or systemic steroid therapy and potentially for steroid-sparing immunomodulatory treatment.

- Possibly lead to a new systemic diagnosis (related to or associated with the ocular disease), for which further workup and treatment may be necessary.

- Provide additional prognostic information on the disease process.

In discussing potential causes of ocular inflammatory disease, it’s important to keep in mind that the goal of lab testing in patients with these conditions isn’t intended so much to uncover a mystery diagnosis in an “ah-hah!” moment, but to guide therapy. We should resist the urge to test exhaustively until a test returns positive.

While some uveitis fits the diagnostic criteria for previously described entities or phenomena, many forms don’t necessarily look the way textbooks might lead you to believe. This doesn’t mean, however, that the disease process won’t respond equally well to pharmacotherapy.

Is there a ‘standard’ workup?

The short answer is no. The disease should be classified based on the clinical exam findings and a well-documented history; then decisions on testing can be made. For example, HLA-B27 testing is reasonable in the setting of acute anterior uveitis, especially if the patient tells you they have been experiencing lower back pain and stiffness. But, it would be less so in a patient who has an occlusive retinal vasculitis or otherwise undifferentiated panuveitis, scenarios in which HLA-B27 positivity wouldn’t be expected. The work-up should be tailored to the patient and their presentation.

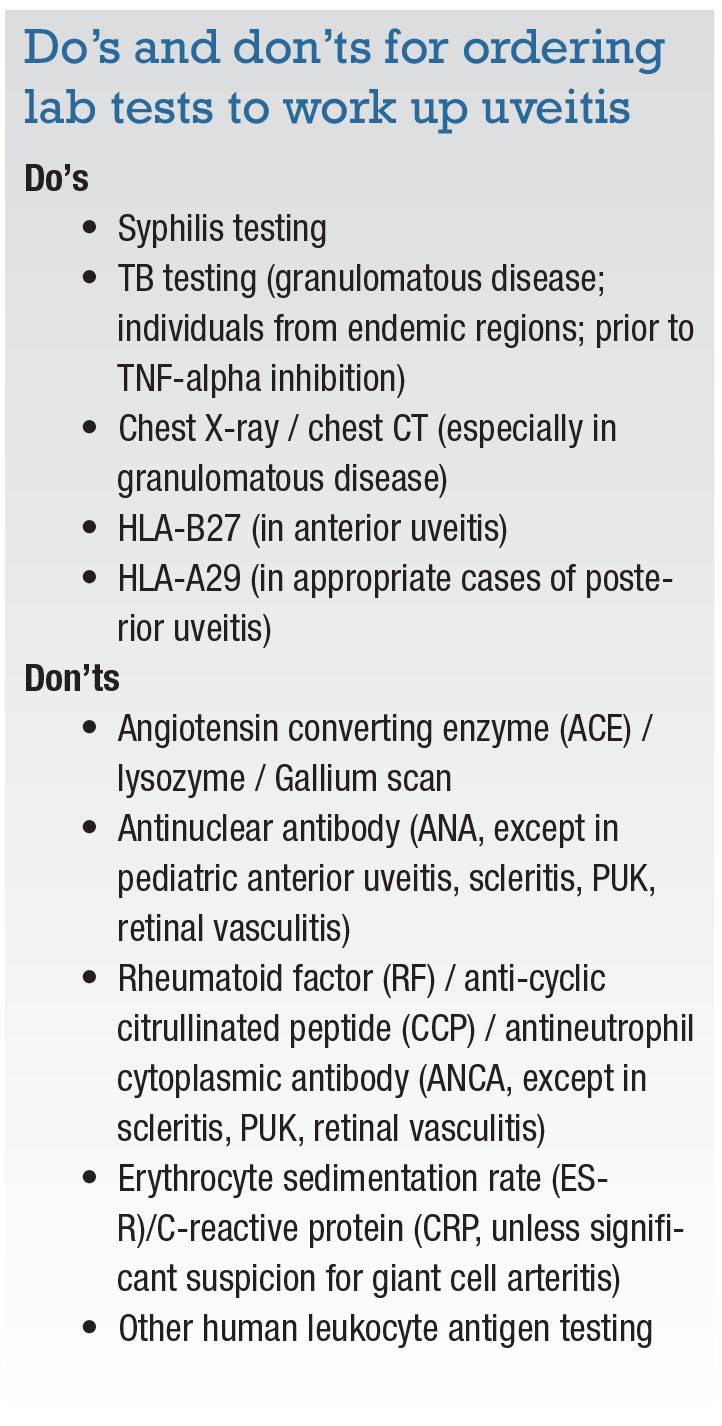

The one condition for which testing is always reasonable, regardless of the type of inflammatory disease, is syphilis. This is the one easily curable cause of pretty much any form of uveitis, and a timely diagnosis can significantly reduce both ocular as well as systemic morbidities. Guidelines for syphilis testing include specific treponemal testing (i.e., fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-Abs], treponema pallidum particle agglutination [TP-PA] assay, T. pallidum immunoglobulin G [IgG], various enzyme immunoassay tests, chemiluminescence immunoassays, immunoblots or rapid treponemal assays), as well as a standard nontreponemal test (i.e., rapid plasma regain [RPR], Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL]) with titers for monitoring treatment response.1 In some cases of ocular syphilis, nontreponemal testing, such as RPR or VDRL may be negative in the presence of active disease.2

If you happen to live in an area where tuberculosis is endemic, specialized testing for TB may also be warranted. There is no perfect laboratory test, but interferon-gamma release assays such as QuantiFERON TB Gold (Quest Diagnostics) and the TB-spot test are reasonable options, the results of which previous bacilli Calmette-Guérin vaccination won’t affect. A positive result may not indicate active TB uveitis (a positive assay and a simultaneous and unrelated immune-mediated process is more likely), but it can be helpful, especially before initiating systemic immunosuppressive agents such as adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) or infliximab (Remicade, Janssen).

|

Human leukocyte antigen typing

There’s little reason not to order HLA-B27 testing in patients with anterior uveitis, especially in those with an alternating, acute disease pattern. It is well accepted that 7 to 8 percent of the general population (without disease) will demonstrate HLA-B27 positivity, so you need to consider the possibility of anterior uveitis and an unrelated positive HLA-B27 allele as well.

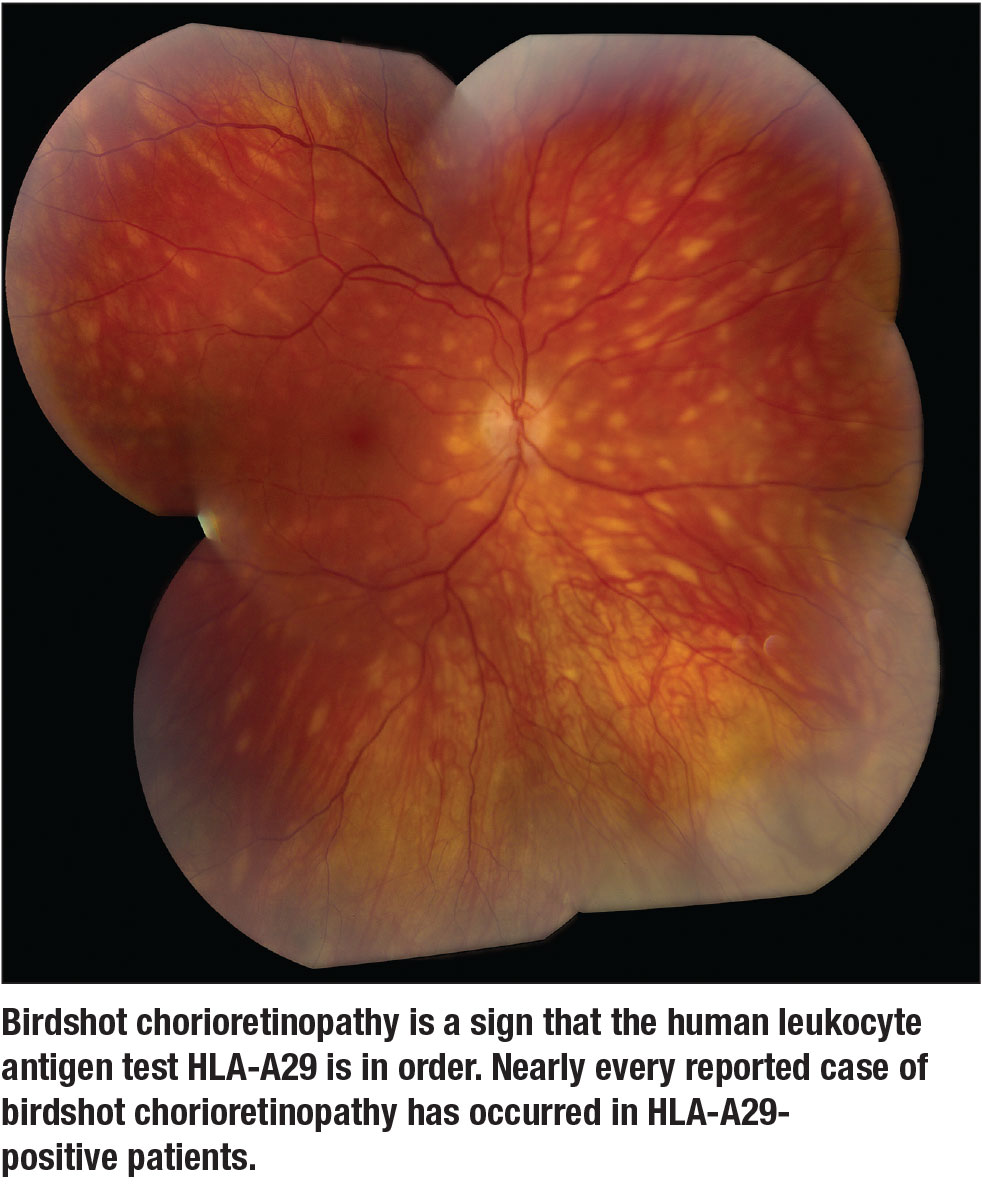

The only other human leukocyte antigen test that has any clinical value is HLA-A29 in the setting of birdshot chorioretinopathy (Figure) or an inflammatory/infiltrative choroidopathy with a similar phenotype. Nearly every reported case of birdshot chorioretinopathy has occurred in HLA-A29-positive patients. Some uveitis specialists don’t believe that seronegative (HLA-A29-negative) birdshot chorioretinopathy exists. A positive test in an individual with bilateral, yellow-orange ovoid choroidal spots essentially confirms the diagnosis, whereas a negative test may lead one to consider other diagnoses, such as lymphoma and sarcoidosis, both of which can closely mimic birdshot.

Tests to Omit

This list includes:

|

• Angiotensin-converting enzyme, lysozyme and gallium scan. One of my mentors frequently reminded us as trainees that the positive predictive value of any one of these examinations in diagnosing sarcoidosis is 20 to 25 percent. A quick review of the pulmonary literature confirms this.3 At best with a positive test, one is likely to incorrectly diagnose sarcoidosis three out of four times. A chest X-ray or CT-scan is more likely to demonstrate hilar adenopathy in the setting of true sarcoidosis. Which of these should be ordered first is somewhat controversial; the decision is ultimately up to the patient and the practitioner ordering the test.

• Serologic testing for Herpesviridae and Toxoplasma. The results of these tests (immunoglobulin M or IgG for HSV 1 and 2, VZV, CMV, Toxoplasma gondii) are helpful only when negative. The rates of seropositivity in the general population are too high to help with diagnosis of anterior and posterior uveitis and panuveitis in which the clinician suspects an infectious etiology. My feeling is that acquiring ocular fluid and PCR analysis is absolutely necessary to rule out or confirm any one of these organisms as the causative agent in ocular inflammatory disease. I typically prefer an aqueous paracentesis (when anterior chamber inflammation is present), but obtaining a specimen via the pars plana may be indicated when pursuing surgery.

|

• Antinuclear antibody (ANA). Clinical scenarios exist in which undiagnosed lupus should be explored as a potential underlying diagnosis: scleritis; ulcerative keratitis; occlusive retinal vasculitis; and inflammatory choroiditis. An ANA, especially in children with anterior uveitis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis, can provide valuable prognostic information. However, in adults, seropositivity can reach as high as 15 percent, and while a positive test may be suggestive of lupus, other clinical findings are necessary to make a diagnosis.

• Rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). I would include this only in cases of scleritis, ulcerative keratitis or retinal vasculitis. Rheumatoid arthritis is not typically associated with uveitis as is the case for ANCA-associated vasculitides.

|

Get it right the first time

It’s difficult to articulate a good reason for not testing after the first episode. The ability to identify an underlying condition with potential systemic morbidity is always of value. Theoretically, it’s better to know early on about these types of scenarios than to allow an infectious or systemic process to declare itself over time.

Being able to provide prognostic information about associated systemic morbidity and likelihood of recurrence alone is reason enough to warrant checking for HLA-B27 positivity in these patients. The SENTINEL study has shown that if a patient is HLA-B27 positive and experiences sudden-onset anterior uveitis, the likelihood of having or developing spondyloarthropathy is 90 percent.4 Those of us who have seen patients with severe spondyloarthropathy in the setting of HLA-B27-associated recurrent acute anterior uveitis, I’m sure, would love to turn back the clock and implement treatment with disease-modifying agents to prevent these types of problems from occurring in the first place.

Every episode of uveitis should be seen as an opportunity to recognize and diagnose associated conditions, but it’s equally important to acknowledge that this may not take place in many cases.

Why we should order testing

Many physicians question who should order the testing for the uveitis workup; if it should be the primary care physician or rheumatologist. When we don’t order our own testing, patients frequently end up undergoing analyses that likely have no impact on or relevance to their disease.

Many non-ophthalmologists (and some ophthalmologists) have difficulty formulating a reasonable differential diagnosis when it comes to ocular inflammatory disease. There seems to be a tendency to over-order testing but to neglect some of the infectious testing that could help inform treatment.

I frequently see patients that have previously been seen by physicians both within and outside of my practice, and that have been subsequently referred to a rheumatologist for a “uveitis workup.” It seems a bit unfair and unreasonable for us to expect that a practitioner with little understanding of these disease processes and how to interpret our exam findings should be able to perform focused, appropriate testing without proper guidance.

When in doubt, a quick e-mail or phone call to an accessible uveitis specialist can provide some valuable insight, especially if the individual initiating the workup is not uveitis fellowship-trained and/or uncomfortable making these types of decisions.

|

Cost-benefit analysis of testing

Several years ago, a study of diagnostic testing practices amongst members of the Executive Committee of the American Uveitis Society (AUS) was conducted. Because there are no guidelines for testing, the results showed a great deal of variation in how testing is performed in a number of different clinical scenarios.5

In calculating the associated costs, the study found that, not surprisingly, radiologic and ophthalmic imaging (not discussed in depth here) are among the most expensive tests ordered, comprising more than half of the testing costs when facility and professional fees are taken into account. A brain MRI, which can be invaluable in ruling out concomitant central nervous system disease in cases of intraocular lymphoma or demyelinating disease in individuals with intermediate uveitis, can cost thousands of dollars. On the other hand, serologic testing, like that for syphilis and QuantiFERON assays, cost around $100 or less. Therefore, we should seriously consider the clinical utility of testing, especially that of radiologic imaging, before sending an order.

Bottom line

It’s important in these situations to think to oneself, “How will these results change the management of this individual’s disease?” More testing simply does not result in better patient care and, in my opinion, often leads to unnecessary additional testing and misuse of resources.

References

1. Syphilis pocket guide for providers. Document CS275410-A. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/Syphilis-Pocket-Guide-FINAL-508.pdf

2. Tamesis SS, Foster CS. Ocular Syphilis. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1281-1287.

3. Ungprasert P, Carmona EM, Crowson CE, Matteson EL. Diagnostic utility of angiotensin-converting enzyme in sarcoidosis: A population-based study. Lung. 2016;194:91-95.

4. Juanola X, Loza Santamarie E, Cordero-Coma M, SENTINEL Working Group. Description and prevalence of spondyloarthritis in a large cohort of patients with anterior uveitis: The SENTINEL Interdisciplinary Collaborative Project. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1632-1636.

5. Lee CS, Randhawa S, Lee AY, Lam DL, Van Gelder RN. Patterns of laboratory testing utilization among uveitis specialists. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;170:161-167.