|

|

A 71-year-old male with a history of factor V Leiden thrombophilia and on oral anticoagulation therapy, and who had a previous right central retinal vein occlusion in 1999, came to the emergency department with left-sided paracentral vision loss.

He reported cloudiness, color distortion and odd shapes in the left lower side of his vision OS. He denied flashes of light, dark spots, curtains in vision or eye pain. He also denied slurred speech, new focal weakness, numbness or facial drooping. He reported that, upon the advice of his primary-care team and anticoagulation clinic, he had switched from Coumadin (warfarin sodium) to Eliquis (apixaban) two weeks earlier and since then had felt minor dizziness and fatigue.

What we found on exam

On examination, best-corrected visual acuity was stable at 20/25 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. Intraocular pressures were 19 and 15 mmHg in the right and left eyes, respectively. Both pupils were round, reactive to light and without an afferent pupillary defect. Confrontational fields and extraocular movements were full in both eyes.

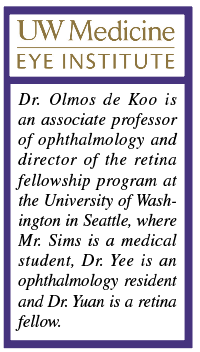

The dilated fundus exam of the right eye revealed collaterals and mild pallor of the disc. The macula was noted to have pigmentary changes, focal laser scars and temporal blot heme. These findings were all consistent with the patient’s history of CRVO after focal laser treatment in the right eye and unchanged from his visit six months earlier. Color fundus photos and fundus autofluoresence in the left eye (Figure 1) demonstrated blot hemorrhages in the superior retina and a tortuous venous system throughout.

|

| Figure 1. A) Fundus photography of the left eye shows blot hemorrhages of the superior hemiretina as well as a tortuous venous system. B) Fundus autofluorescence of the eye highlights the blot hemorrhages in the superior retina. C) Fundus photography of the left eye two weeks after the initial visit shows increased blot hemorrhages (arrows) now involving the entire retina and a new flame hemorrhage off the optic nerve superotemporally. |

Work-up

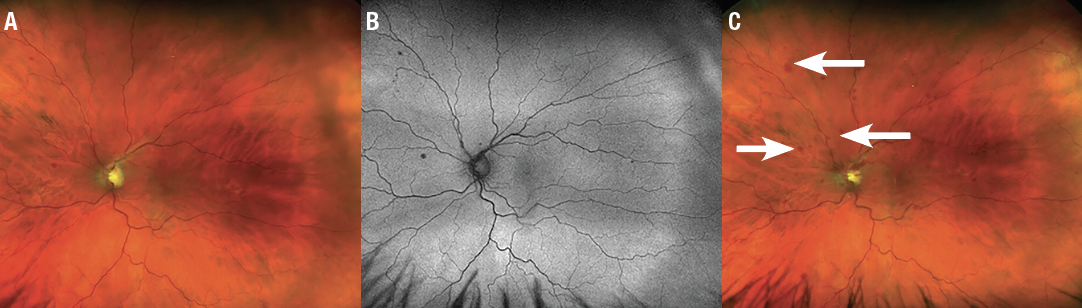

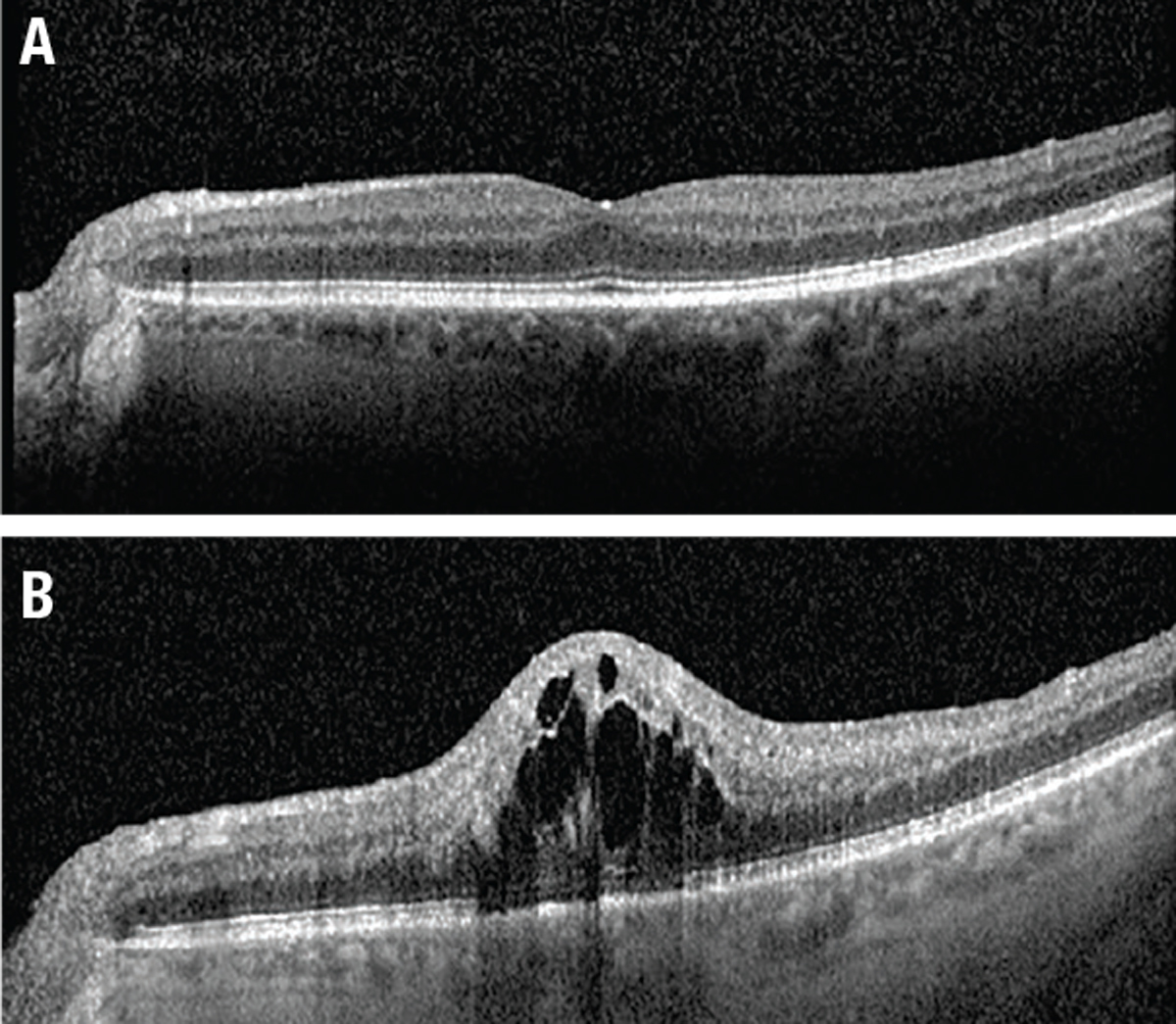

Optical coherence tomography, fundus photos and fluorescein angiography were performed to document and assess the newly decreased vision in the left eye. OCT of the right eye revealed retinal atrophy and mild paracentral cysts stable from a year ago. OCT of the left showed a normal foveal contour and no intraretinal or subretinal fluid, also stable from a year ago. Fluorescein angiogram demonstrated delayed superior venous filling and slow, late disc leakage (Figure 2).

Diagnosis and management

The patient’s history of factor V Leiden and remote history of CRVO in the fellow eye, coupled with his report of acute subjectively decreased paracentral vision with visual acuity of 20/20 in the left eye, plus the presence of intraretinal hemorrhages and delayed superior venous filling on FA, were consistent with a diagnosis of impending hemiretinal vein occlusion.

|

| Figure 2. Fluorescein angiogram of the left eye at three different intervals: A) 26 seconds; B) 37 seconds; and C) 3 minutes, 18 seconds. The FA showed delayed superior venous filling and slow, late disc leakage, but no ischemia. |

We paged the patient’s primary-care team and anticoagulation clinic and arranged for him to restart his warfarin therapy. We offered the patient topical IOP-lowering therapy with brimonidine twice daily, with the rationale of increasing ocular perfusion pressure. We also followed him closely in the clinic.

Two weeks later, he restarted warfarin and his prothrombrin time (PT) was back within goal at 2.4. VA remained 20/20, but subjectively his vision had worsened and on exam he showed increased blot hemorrhages now spreading to involve the entire retina and a new flame hemorrhage off the optic nerve (Figure 1C). OCT remained stable without macular edema. We-added another nonprostaglandin IOP-lowering agent because his IOP stabilized at 14 mmHg.

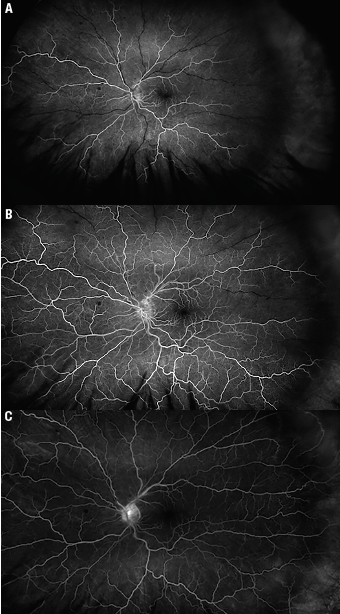

Three weeks later, and five weeks after his initial presentation, the patient returned with reduced VA of 20/60 and new macular edema on OCT. We treated him with intravitreal bevacizumab.

RVO and anticoagulation

Given the timing of this patient’s symptoms after switching from warfarin to apixaban, it’s possible that his PT was temporarily subtherapeutic, contributing to the development of RVO. This case demonstrates the importance of closely monitoring patients with a history of thrombophilic disorders, such as factor V Leiden, when switching anticoagulant medication, particularly in those with a previous RVO. It also highlights the challenges in diagnosis and management of impending retinal vein occlusion.

RVO is a leading cause of vascular blindness. Risk factors associated with CRVO include hypertension, open-angle glaucoma and diabetes mellitus.1 Risk factors for BRVO include hypertension, open-angle glaucoma, cardiovascular disease and high body-mass index.2 One of the most significant risk factors for developing RVO is an RVO in the contralateral eye. People with BRVO in one eye have a 10 percent risk of developing a BRVO in the contralateral eye within three years.3 The risk of contralateral involvement in a patient with CRVO increases 1 percent every year and jumps to 7 percent after five years.3,4

RVO and patient age

|

| Figure 3. A) Optical coherence tomography at presentation shows no macular edema. B) Five weeks later, OCT shows diffuse central cystic intraretinal fluid. |

When diagnosing RVO in older patients with cardiovascular risk factors, laboratory tests may not be indicated. If the patient is younger, as our patient was in 1999 when he was first diagnosed with CRVO in his right eye, or has none of the typical risk factors, laboratory tests such as complete blood count, fasting serum glucose and thrombophilic screening (factor V Leiden, protein C and S, and antiphospholipid antibodies) may be considered. A carotid duplex may also be helpful.

Currently, there’s no treatment available to reverse RVO. Radial optic neurotomy surgery remains controversial in CRVO cases, but would be ruled out when the VA is relatively preserved.5 Common complications of RVO are macular edema and neovascularization.

Anti-VEGF injections are now the first-line treatment for macular edema and iris neovascularization.6 Triamcinolone has been shown to improve macular edema in CRVO but not BRVO.7 Patients with RVO should be monitored closely for macular edema or neovascularization during the first six months after diagnosis. RS

REFERENCES

1. The Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:545-554.

2. The Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Risk Factors for branch retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:286-296.

3. Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB, Podhajsky P. Incidence of various types of retinal vein occlusion and their recurrence and demographic characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117:429–441.

4. [No authors listed] Natural history and clinical management of central retinal vein occlusion. The Central Vein Occlusion Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:4:486–491.

5. Feltgen N, Hansen LL, Agostini H. Behandlung des retinalen Venenverschlusses—Welche Rrolle spielt die Vitrektomie heute noch? [Treatment of retinal vein Occlusion—Is there still a role for vitreoretinal surgery?]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2017;234:1103-1108.

6. Ciftci S, Sakalar YB, Unlu K, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab combined with panretinal photocoagulation in the treatment of open angle neovascular glaucoma. Euro J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:1028-1033.

7. Scott IU, Ip MS, VanVeldhuisen PC, et al. A randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of intravitreal triamcinolone with standard care to treat vision loss associated with macular edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion: the Standard Care vs Corticosteroid for Retinal Vein Occlusion (SCORE) study report 6. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1115-1128.