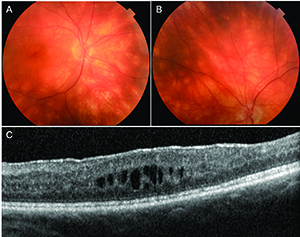

cream-colored lesions about 1/4 disc diameter in size.

Some of the more peripheral lesions are ovoid in

appearance. In the left eye (B), round and ovoid

cream-colored lesions deep to the retinal vessels were

visible. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography of

the macula OD (C) revealed cystic intraretinal fluid, most

of which localized to the inner nuclear layer, although all

layers from the inner plexiform to the outer nuclear layer

were involved. The ellipsoid zone band and retinal pigment

epithelium were intact and no subretinal fluid was present.

She reported difficulty seeing in the dark and against dark backgrounds. She said she was concerned that she could not locate small items at work when they fall to the floor, which is dark in color. “I am looking for answers,” she said.

Medical History and Exam

The patient has a history of cervical cancer, resected four years previously without recurrence. Otherwise, ocular and medical histories were unremarkable. She takes the antidepressant citalopram 20 mg PO daily for generalized anxiety disorder. She has a 10-plus pack-year history of smoking but she denied abuse of alcohol or other drugs.Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/30-1 and 20/30+1, with intraocular pressures of 12 and 13 mmHg OD and OS, respectively. Pupils were normal without afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular movements and confrontation visual fields were full OU.

The anterior segment exam was normal OU. We noted 1+ anterior vitreous cell and many round, cream-colored lesions deep to the retinal vessels extending from the optic disc and the vascular arcades out to the equator in both eyes. These lesions appeared less round and more ovoid as they extended peripherally (Figures 1A and B).

Diagnosis and Workup

Given the vitritis and the characteristic, symmetric, cream-colored lesions in both eyes, the differential diagnosis centered on the primary inflammatory choriocapillaropathies, also known as the white spot (or dot) syndromes. These include bird-shot chorioretinopathy, acute zonal occult outer retinopathy, multiple evanescent white dot syndrome and multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis.1We also considered infectious etiologies such as tuberculosis, syphilis and presumed ocular histoplasmosis. Although these etiologies are less likely, their management greatly differs from the white spot syndromes.

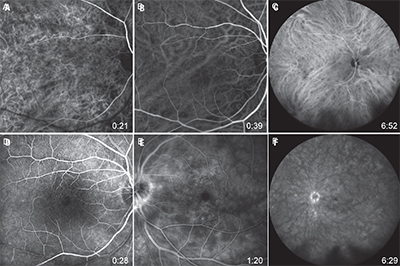

the right eye: at 21 seconds (A), a somewhat patchy appearance to the choroid

with mild hyperfluorescence and some fuzziness to the choroidal vessels,

especially in the superior macula, with a few round hypofluorescent lesions;

at 39 seconds (B), a more normal appearance, but again with a mild fuzzy

quality to some of the choroidal vessels; and at 6:52 (C), many round and ovoid

hypofluorescent lesions. Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the right eye, at 28

seconds (D), revealed a few areas of arteriolar narrowing and some mild

pruning, with a few mildly hyperfluorescent terminal vascular bulbs, likely

representing microaneurysms. In the left eye, FA, at 1:20 (E), revealed a small

peripapillary rim of hyperfluorescence with patchy, background

hyperfluorescence and many small hyperfluorescent foci throughout the

macula; and at 6:29 (F), conveyed a dense hyperfluorescent, peripapillary ring.

The background conveyed patchy and mild hyperfluorescence. Multiple, small

hyperfluorescent foci near the vessels inferior to the disc were visible, as were

many small, faint, hyperfluorescent foci in the macula.

Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) revealed speckled hyperautofluorescence surrounding the disc OU. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the macula revealed fine vitreous opacities, small, cystic intraretinal fluid and an epiretinal membrane in both eyes (Figure 1C). Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) revealed many hypofluorescent patches corresponding to the cream-colored lesions OU (Figures 2A-C).

Fluorescein angiography (FA) revealed a few areas of arteriolar narrowing and some mild pruning with a few mildly hyperfluorescent terminal vascular bulbs, likely representing microaneurysms. During early venous filling, a small peripapillary rim of hyperfluorescence began to form, which became a densely hyperfluorescent peripapillary ring on later phases. There were also many small, round hyperfluorescent foci surrounding the fovea, which increased in intensity but not diameter, in the later phases of FA (Figures 2D-F).

Treatment Plan

We determined that the patient’s clinical presentation was consistent with bird-shot chorioretinopathy with cystoid macular edema (CME) OU. We started her on cyclosporine 100 mg PO daily and prednisone 5 mg PO daily. We placed the dexamethasone intravitreal implant (Ozurdex, Allergan) in each eye, one week apart, to achieve local control of the inflammation and CME.We counseled the patient to stop smoking because smokers have an increased risk of developing noninfectious uveitis and uveitis with CME. However, she explained that she is not ready to quit.2-4 We also ordered further testing, including complete metabolic profile (CMP), complete blood count (CBC) and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) A29 to confirm the diagnosis.

Discussion

Bird-shot chorioretinopathy, previously termed vitiliginous chorioretinopathy, is a bilateral, chronic uveitis that may present with vitritis, retinal vasculitis and cystoid macular edema.1 The term bird-shot chorioretinopathy was coined by Stephen J. Ryan, MD, and A. Edward Maumenee, MD, in 1980, to describe the manner in which the lesions scatter away from the optic disc and toward the equator, giving a “shotgun” appearance.5Bird-shot chorioretinopathy has the strongest link to HLA class I antigen of any disease in medicine, with a positive antigen HLA-A29 conferring a relative risk of 49.9.6 It is a rare disease, accounting for 6 to 7.9 percent of patients with posterior uveitis. Slightly more than half of patients are women, and all but two reported cases have been in Caucasian patients.7

The presentation is classically described as involving oval or round, cream-colored lesions, about 1/2 to 1/4 disc diameter in size that are deep to the retina, cluster near the nerve, and are more predominant inferior and nasal to the disc.1,8 As the lesions track further toward the equator, they may become more ovoid in appearance; vitritis may be present, but anterior chamber cell is typically absent or mild.1,5

These bird-shot lesions are not usually seen on FA, but appear on ICGA as hypofluorescent lesions during the early stages of the disease, and may represent blockage from inflammatory infiltrates or, less likely, choroidal ischemia.9

|

| Dr. Olmos de Koo is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Southern California Eye Institute and director of the vitreoretinal fellowship at the Keck School of Medicine of USC in Los Angeles. Dr. Moysidis is an ophthalmology resident at the USC Eye Institute/Los Angeles County + USC program. Dr. George is a senior surgical vitreoretinal fellow at USC Eye Institute. |

The pathophysiology remains only partially elucidated with pathologic specimens revealing accumulation of primarily CD8+ T-lymphocytes within choroidal vessels.11

The most common cause of vision loss in these patients is secondary to CME, while choroidal neovascularization (CNV) develops in only 5 percent of eyes but results in more severe vision loss. CNV in cases of bird-shot chorioretinopathy is thought to occur secondary to a uveitic rather than an ischemic mechanism.1,12

Little consensus exists on management of bird-shot chorioretinopathy. Oral corticosteroids have long been the mainstay of treatment, and many physicians include a second immunosuppressive medication as well. Low-dose cyclosporine 100 mg PO daily has been shown to be efficacious with concurrent lower-dose oral corticosteroid.13

The patient must be monitored for nephrotoxicity and hypertension while on cyclosporine. Recently, intravitreal injections of sustained- release fluocinolone acetonide and dexamethasone have been delivered to allow for higher potency and localized drug delivery. However, an increased risk of cataract and glaucoma with these modalities has been reported.14,15

Smoking confers 2.96 times greater odds of developing noninfectious uveitis and 3.9 to eight times greater odds of uveitis with CME. Thus, physicians should discuss tobacco cessation with these patients.2-4 The treatment plan should be optimized for each individual patient. RS

References

1. Mirza RG, Jampol LM. White Spot Syndromes and Related Diseases. Retina 5th ed. 2012;2:1337-1380.2. Lin P, Loh AR, Margolis TP, Acharya NR. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:585-590.

3. Thorne JE, Daniel E, Jabs DA, Kedhar SR, Peters GB, Dunn JP. Smoking as a risk factor for cystoid macular edema complicating intermediate uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:841-846.

4. Yuen BG, Tham VM, Browne EN, et al. Association between Smoking and Uveitis: Results from the Pacific Ocular Inflammation Study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1257-1261.

5. Ryan SJ, Maumenee AE. Bird-shot retinochoroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89:31-45.

6. Nussenblatt RB, Mittal KK, Ryan S, Green WR, Maumenee AE. Bird-shot retinochoroidopathy associated with HLA-A29 antigen and immune responsiveness to retinal S-antigen. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;94:147-158.

7. Shah KH, Levinson RD, Yu F, et al. Bird-shot chorioretinopathy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50:519-541.

8. Gasch AT, Smith JA, Whitcup SM. Bird-shot retinochoroidopathy. Br J Ophthalmol.1999;83:241-249.

9. Fardeau C, Herbort CP, Kullmann N, Quentel G, LeHoang P. Indocyanine green angiography in bird-shot chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1928-1934.

10. Levinson RD, Brezin A, Rothova A, Accorinti M, Holland GN. Research criteria for the diagnosis of bird-shot chorioretinopathy: results of an international consensus conference. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:185-187.

11. Gaudio PA, Kaye DB, Crawford JB. Histopathology of bird-shot retinochoroidopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1439-1441.

12. Brucker AJ, Deglin EA, Bene C, Hoffman ME. Subretinal choroidal neovascularization in bird-shot retinochoroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:40-44.

13. Vitale AT, Rodriguez A, Foster CS. Low-dose cyclosporine therapy in the treatment of bird-shot retinochoroidopathy. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:822-831.

14. Yap YC, Papathomas T, Kamal A. Results of intravitreal dexamethasone implant 0.7 mg (Ozurdex(R)) in non-infectious posterior uveitis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015;8:835-838.

15. Rush RB, Goldstein DA, Callanan DG, Meghpara B, Feuer WJ, Davis JL. Outcomes of bird-shot chorioretinopathy treated with an intravitreal sustained-release fluocinolone acetonide-containing device. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:630-636.