The study involved 3,306 patients with noninfectious uveitis and 5,270 uveitic eyes seen at five uveitis clinics in the United States between 1979 and 2007. The main outcome was prevalent and incident ocular hypertension (OHT) with intraocular pressures (IOPs) of ≥21 mmHg, ≥30 mmHg and increase of ≥10 mmHg from baseline or need for treatment.

Among

|

The study identified the following statistically significant risk factors (and adjusted hazard ratios [aHR]) for incident OHT ≥30 mmHg:

Systemic hypertension (1.29).

Presenting visual acuity of ≤20/200 vs. ≥20/40 (1.47).

Pars plana vitrectomy (1.87).

History of OHT in the other eye: IOP ≥21 mmHg (2.68); ≥30 mmHg (4.86); and prior/current use of IOP-lowering drops or surgery in the other eye (4.17).

Anterior chamber cells 1+ (1.43) and ≥2+ (1.59) vs. none.

Epiretinal membrane (1.25).

Peripheral anterior synechiae (1.81).

Current prednisone use >7.5 mg/day (1.86).

Periocular corticosteroids in the last three months (2.23).

Current topical corticosteroid use of more than eight times a day vs. none (2.58).

History of fluocinolone acetonide implants (9.75).

The study authors also identified two predictors of statistically lower risk of OHT: a history of bilateral uveitis (aHR, 0.69); and a history of hypotony (aHR, 0.43).

“Patients with one or more of the several risk factors identified are at particularly high risk and must be carefully managed,” concluded lead author Ebenezer Daniel, MBBS, PhD, of Scheie Eye Institute, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“Modifiable risk factors, such as use of corticosteroids, suggest opportunities to reduce OHT risk within the constraints of the overriding need to control the primary ocular inflammatory disease,” Dr. Daniel and colleagues stated.

REFERENCE

1. Daniel E, Pistilli M, Kothari S, et al., for the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Research Group.. Risk of ocular hypertension in adults with noninfectious uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2017;April 19 [Epub ahead of print]

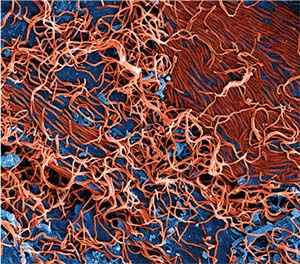

Previously Unseen Retinal Lesions Reported in Ebola Survivors

As reports of new Ebola cases trickle out of western Africa, investigators have identified previously unseen retinal lesions in survivors of previous outbreaks, according to a study published in the journal Emerging Infectious Disease.1

Paul J. Steptoe, of the University of Liverpool and Royal Liverpool Hospital, and colleagues from the U.K. and Sierra Leone conducted a prospective, case-control study in that country to determine if Ebola virus disease (EVD) had any specific effects on the back of the eye. They subclassified retinal lesions into 10 different groups, and noted type 6 subcategory lesions appeared exclusively in the EVD survivors. The presentation was bilateral in half of them.

The study involved 82 EVD survivors and 105 controls that had ophthalmic examinations. The researchers reported that 14.6 percent of EVD survivors (97.5 percent confidence interval [CI], 7.1–25.6) had the novel retinal lesion along optic nerve axons. They observed any retinal lesions other than type 6 in 21 of 82 patients

|

| Colorized scanning electron micrograph of filamentous Ebola virus particles (red) attached and budding from a chronically infected VERO E6 cell (blue) (25,000-x magnification). National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health photo. |

The distribution of the retinal lesions in EVD survivors suggests a spread from the optic nerve and along retinal ganglion cell axons. In the eight cases in which lesions appeared adjacent to the optic disc, their curvilinear projections from the disc margin appeared to align with the anatomic pathways of the retinal ganglion cell axons that constitute the optic nerve. The other possible mode of entry into the eye is hematologic, but the study found no signs of associated vascular involvement.

With regard to appearance of the lesions, the study authors described characteristic angulated borders like a diamond or wedge not found in any other retinal lesion. And despite the close proximity of the lesions to the optic nerve, the study noted no optic nerve inflammation or pallor, and the EVD retinal lesions did not affect visual acuity. Cataract was the most common cause of visual impairment in EVD survivors. This study suggests testing the anterior chamber for Ebola before proceeding with cataract surgery in EVD survivors.

The Democratic Republic of Congo reported an outbreak of four Ebola cases and four deaths in May, but no new confirmed cases since. In Sierra Leone, almost 4,000 people died and about 10,000 survived previous Ebola outbreaks. RS

REFERENCE

1. Steptoe PJ, Scott JT, Baxter JM, et al. New retinal lesions in Ebola survivors, Sierra Leone, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017:23:10.3201/eid2307.161608.