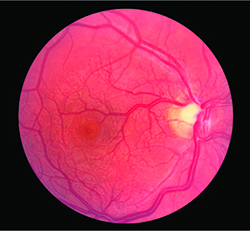

vessels around the nerve and fovea and

engorged veins in three quadrants.

Medical History

The patient’s ocular and medical histories were unremarkable. He was not taking any medications and he had no allergies. Another provider had seen him a few days earlier for the same complaint, and he had a brain MRI that was normal.Examination

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/30-1 and 20/20, with intraocular pressures of 9 mmHg and 10 mmHg in the right and left eyes, respectively. No afferent pupillary defect was present. Extraocular movements and confrontational visual fields were full in both eyes. The anterior segment exam was unremarkable.Ophthalmoscopy revealed telangiectatic vessels around the nerve and fovea (Figure 1), and engorged veins inferotemporally, inferonasally and superonasally. There was no readily apparent arteriovenous anastomosis. The left eye was normal.

Diagnosis, Workup, Treatment

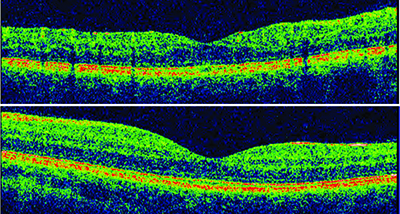

Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the right eye highlighted the tortuous, dilated vessels, particularly around the nerve and in the macula. There were no vessel leakage and filling defects. Angiography of the left eye was unremarkable.Given the concentration of pathology in the posterior pole, we performed optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the macula and optic nerve retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL). OCT of the macula revealed thinning and disorganization of the retina in the right eye (Figure 2), suggesting an underlying and long-standing ischemia and atrophy. The left eye was normal as was the RNFL in both eyes.

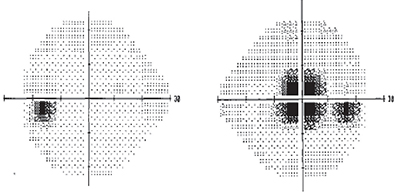

To characterize the ring scotoma the patient described, we performed visual field testing, which revealed a central scotoma in the right eye while the left eye was normal (Figure 3). Over a two-week period, the patient’s examination and subjective findings remained stable, but he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Discussion

| ||

| Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography of the right eye (top) showed macular thinning and disorganization of the retina, while the left eye (bottom) was normal. | ||

| ||

| Figure 3. Visual field testing revealed a central scotoma in the right eye (left), while the left eye was normal. |

In contrast, high-altitude retinopathy (HAR) is a pathological entity documented in only a subset of individuals exposed to high altitudes. They demonstrate retinal hemorrhages, optic nerve edema, or both, and in at least one case, new cotton wool spots.3-7 While not absolute, these abnormalities generally have resolved upon return to sea level.

At first blush, the extent and duration of our patient’s pathology seems out of proportion to the insult he encountered. As such, we hypothesized that the symptoms resulted not only from the effects of altitude, but also from preexisting retinal pathology and his exertion at altitude.

Despite the lack of arteriovenous malformations on funduscopy widefield imaging, we were interested in this possibility, given the presence of tortuous vessels in the posterior pole on examination and ischemic changes to the macula on OCT.

A 2008 review found 57 of 121 documented examples of retinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) in isolation that were not associated with congenital retinocephalofacial vascular malformation syndrome (Wyburn-Mason syndrome or Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome) or intracranial AVMs occurring at the same time.9

|

| Dr. Olmos de Koo is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at University of Southern California Eye Institute at the Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, and director of its vitreoretinal fellowship program. Dr. Bergman is an ophthalmology resident at the USC Eye Institute/Los Angeles County + USC program. Dr. Ameri is an assistant professor and director of the USC Eye Institute’s Retinal Degeneration Center. |

The impact of altitude on the retina is thought to be secondary to the hypoxic environment. So, we would expect that exercise at high altitude would potentiate the deleterious effect on the retina. The literature has borne this out. D. Murray McFadden, MD, and colleagues reported a higher incidence of retinal hemorrhages in subjects exercising at high altitude than those resting at high altitude or exercising at sea level.1

Furthermore, individuals suffering from chronic hypoxia might be expected to have a lower threshold for retinal damage in light of hypoxic conditions. To this end, there is a report of a patient with cystic fibrosis who developed retinal vessel tortuosity and retinal hemorrhage after hiking at 4,900-9,800 feet.9 Similarly, our patient’s chronically hypoxic macula may have lowered the threshold for the functional impact of exercise at 10,800 feet, creating a triad of hypoxic events—congenital malformation, ascent to altitude and strenuous exercise. RS

References

1. McFadden DM, Houston CS, Sutton JR, Powles AC, Gray GW, Roberts RS. High-altitude retinopathy. JAMA. 1981;245:581-586.2. Singh I, Khanna PK, Srivastava MC, Lai M, Roy SB, Subramanyam CS. Acute mountain sickness. N Eng J Med. 1969;280:175-184.

3. Frayser R, Houston CS, Bryan AC, Rennie ID, Gray G. Retinal hemorrhage at high altitude. N Eng J Med. 1970;282:1183-1184.

4. Wiedman M. High altitude retinal hemorrhage. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:401-403.

5. Shults WT and Swan KC. High altitude retinopathy in mountain climbers. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:404-408.

6. Karakucuk S and Mirza GE. Ophthalmological effects of high altitude. Ophthalmic Res. 2000;32:30-40.

7. Bosch MM, Barthelmes D, Merz TM, et al. High incidence of optic disc swelling at very high altitudes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;26:644-650.

8. Schmidt D, Pache M, Schumacher M. The congenital unilateral retinocephalic vascular malformation syndrome (Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome or Wyburn-Mason syndrome): Review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:227-249.

9. Rimsza ME, Hernried LS, Kaplan AM. Hemorrhagic retinopathy in a patient with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1978;62:336-338.