| ABOUT THE AUTHOR |

Dr. Mein is president of Retinal Consultants of San Antonio and clinical professor of ophthalmology at University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. Dr. Mein is president of Retinal Consultants of San Antonio and clinical professor of ophthalmology at University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. |

| Disclosures: Dr. Mein has equity in Regeneron, is a DRCR.net investigator and receives research funding from Alcon, Allergan and Iconic. |

The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) recently published the two-year results of Protocol S1 that compared panretinal photocoagulation and intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genentech) for patients with high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Protocol S was designed as a noninferiority study to determine if intravitreal ranibizumab was noninferior to PRP for treatment of high-risk PDR. The study authors concluded that treatment with intravitreal ranibizumab resulted in visual acuity that was noninferior to PRP at two years.

PRP Comes at a Price

PRP has been the mainstay for treatment of PDR since the Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group reported its results in the 1970s.2 Those of us who have been in practice for more than two decades have had many patients with PDR who received PRP, resulting in stabilization of vision and retinopathy for years without further treatment.

However, PRP comes at a price. Side effects include loss of peripheral vision, development of diabetic macular edema and difficulty with night vision, especially if the patient receives the recommended 2,000–3,000 burns. Should we now consider using pharmacotherapy with anti-VEGF injections instead of PRP for the treatment of PDR?

As we have moved to treatment to inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor and away from focal/grid laser for DME based on DRCR.net Protocol I, we have noticed a reduction in the progression of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy to PDR. Thus, the DRCR.net set its primary endpoint accordingly.

|

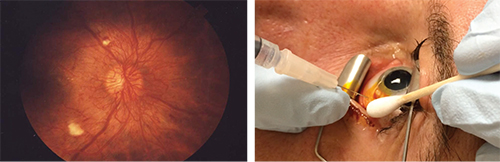

| Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (left) can have a debilitating affect on vision, but the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Protocol S reports that in select patients, especially those with combined PDR and diabetic macular edema, treatment of PDR with anti-VEGF therapy is noninferior to panretinal photocoagulation and may provide distinct advantages such as better visual acuity, reduced loss of visual field and better night vision. |

Protocol S randomized eyes to receive one to three sessions of PRP treatment (203 eyes) or ranibizumab 0.5 mg intravitreal injection at baseline and then every four weeks (191 eyes). A structured retreatment protocol determined repeat injections based on optical coherence tomography and clinical findings. Eyes with DME received ranibizumab in both groups.

After two years of follow-up, the ranibizumab group improved 2.8 letters while the PRP group improved by only 0.2 letters. With a P value of 0.001, the results showed that ranibizumab as given in this study was not inferior to PRP.

Visual acuity was better under the curve for the ranibizumab group for the entire two-year study period. Visual field sensitivity loss was worse in the PRP group. Vitrectomy was more frequent in the PRP group (15 percent) than the ranibizumab group (4 percent), as was the development of DME.

Clinical Implications

As a practicing ophthalmologist seeing patients with high-risk PDR, how will the results of Protocol S change my approach? When a new patient presents with PDR, several key factors need to be addressed.

The most important is patient compliance and reliability. For me to consider anti-VEGF therapy as the primary treatment, I must be assured that the patient will return for follow-up and more injections. I do not want the give the patient one injection only to have her or him return some months later with severe progression of PDR when a PRP would have stabilized the condition.

| Take-home Point The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Protocol S has given us a new approach to high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy. While panretinal photocoagulation remains the primary treatment for PDR in many patients, anti-VEGF therapy should be an option for patients who are reliable and present with PDR and diabetic macular edema. |

Perhaps the best approach would be a hybrid approach of anti-VEGF initially for three injections followed by PRP for more long-term stability. This approach would require a lighter amount of PRP, thus reducing the adverse effects on peripheral vision and development of DME.

Many of my patients who have had full PRP still manifest neovascularization elsewhere (NVE) on widefield fluorescein angiography. These patients are ideal for anti-VEGF therapy.

DRCR.net Protocol S has given us a new treatment paradigm for high-risk PDR without the side effects of PRP. For eyes with high risk-PDR and DME, anti-VEGF therapy seems to be the treatment of choice. For eyes with high risk-PDR without DME, a combination of PRP for stability and anti-VEGF therapy to prevent DME would be a good choice. For eyes that have had extensive PRP and still have active NVE, anti-VEGF should be considered.

These clinical situations have no exact answers, and as practicing retina specialists we will have some very exciting discussions about the best approach for high-risk PDR now that DRCR.net has given us the Protocol S results. I look forward to the five-year results of this important ongoing clinical trial. RS

REFERENCES

1. Writing Committee for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Gross JG, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, et al. Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015:314:2137-2146.

2. Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Preliminary report on effects of photocoagulation therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;81:383-396.