|

Why Do It?

Several indications exist for invasive biopsy of the posterior segment of the eye. They include persistent uveitis of unknown cause and to obtain samples of some intraocular tumors. Usually a diagnostic vitrectomy, for purely vitreous-involving disease, or transvitreal fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), for choroidal lesions, is sufficient. However, FTRCB may be indicated in exceedingly rare instances with full-thickness retina/subretinal involvement and where conventional methods fail to yield a diagnosis, when malignancy or infection is suspected, or a histologic specimen will alter the treatment plan.

For many of our patients with posterior or panuveitis, we can make a diagnosis clinically with non-invasive ancillary diagnostic tests. However, an FTRCB may be indicated in a handful of specific instances.

After taking a comprehensive ocular and systemic history, these challenging situations require we utilize all available diagnostic modalities. Fluorescein angiography, B-scan ultrasonography, indocyanine green angiography and high-definition ocular coherence tomography may all provide potentially important diagnostic information. Moreover, systemic blood work for autoimmune, neoplastic and infectious etiologies is often necessary, and systemic computed-tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging may also be indicated.

Vitreoretinal Lymphoma

In those patients with obvious retina/subretinal lesion and where diagnostic measures fail to confirm a diagnosis, the patient is unresponsive to therapy, or if the fellow eye is threatened despite seemingly appropriate therapy, one may consider a FTRCB procedure to help guide treatment.1-5

Between 2.3 and 2.5 percent of all patients with an initial presenting diagnosis of uveitis have been eventually diagnosed with a malignancy, with primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL) representing the most common neoplastic masquerade syndrome.6,7 In cases where PVRL is suspected, brain/spinal MRI and lumbar puncture may help identify coexisting central nervous system disease. For both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, a vitreous specimen can be sent for cytology, flow cytometry, IL-10/IL-6 ratios and IgH gene rearrangements.8

|

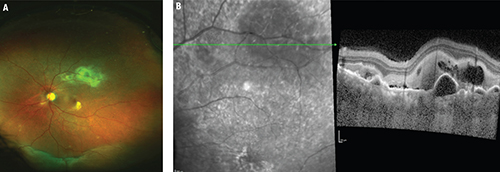

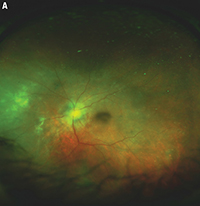

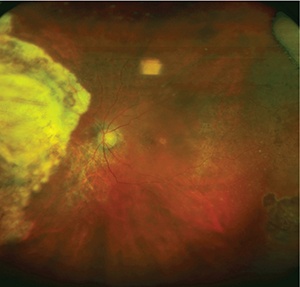

| Figure 1. On exam (A), this patient had an inferior retinal detachment, shallow submacular fluid associated with hard exudates and subretinal fibrosis. Creamy subretinal infiltrates along the superotemporal arcade were also visible. Optical coherence tomography (B) with a cut through the superotemporal arcade showed dilated choroidal vasculature, multiple pigment epithelial detachments and hyperreflective subretinal infiltration. |

Another scenario where a FTRCB may be required is if an infectious cause of posterior or panuveitis is suspected and the results of the biopsy will alter the treatment plan. Despite knowing the classic patterns of presentation of viral or bacterial retinitis, some conditions may produce an atypical clinical picture especially in immunocompromised patients.

Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the aqueous and/or vitreous is widely available, with good positive and negative predictive values.10 However, cases have been reported where this may not yield an answer and a FTRCB may be necessary to determine the proper course of treatment.

Perhaps the best way to both demonstrate the indications for this procedure and to discuss the finer points of performing the surgery itself is to consider the case of a patient who presented to our clinic.

Case: Exudative Retinal Detachment With Choroiditis

A 70-year-old woman presented with a chronic-appearing exudative retinal detachment associated with choroiditis and a focal area of creamy subretinal infiltrates in the left eye. She had no light perception in the fellow eye due to a previous complicated rhegmatagenous retinal detachment. Her medical history was significant only for idiopathic proteinuria, for which she was taking oral prednisone.

| Take-home Point Full thickness retino-choroidal biopsy (FTRCB) has been difficult to perform, but with the emergence of small-gauge instruments, this procedure may be becoming more feasible for vitreoretinal surgeons. This article discusses indications and steps involved in performing FTRCB. |

OCT (Figure 1) demonstrated significant choroidal thickening with dilated choroidal vasculature, diffuse SRF extending inferiorly, multiple pigment epithelial detachments and hyperreflective subretinal infiltration under the superotemporal arcade. Fluorescein angiography imaging showed patchy choroidal filling followed by multiple hyperfluorescent points with late leakage and staining of subretinal fibrosis. No signs of vasculitis or papillitis were present.

A comprehensive systemic workup was within normal limits except for the aforementioned proteinuria. A diagnostic vitrectomy and transvitreal FNAB also did not yield a diagnosis. At that point the patient had also been unresponsive to a six-week course of systemic corticosteroids.

So here we are with a patient who is monocular, has a vision-threatening process that was unresponsive to treatment and in whom conventional methods failed to yield a diagnosis. We decided to perform a FTRCB with the hope that a histologic specimen would help make a definitive diagnosis and guide further treatment.

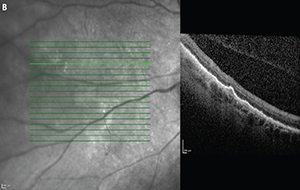

| Figure 2. This 62-year-old woman also required full-thickness retino-choroidal biopsy (FTRCB). She presented with subacute vision loss and was found to have active creamy yellow/white infiltrates in the nasal/inferior midperiphery (A). On optical coherence tomography (B), the finding appeared to be largely confined to the subretinal space and to be less impressive than the previous case. She had rapidly progressive vision loss in both eyes over a few weeks and an entirely negative workup, which prompted the FTRCB. |

|

FTRCB is one of the more challenging retinal procedures you may perform, so meticulous planning is an absolute necessity. Here are key steps involved in the process:

• Communicate with your pathologist. You’ll want to discuss storage media and transportation means for your specimen, and you may even consider asking the pathologist to be present in the operating room to confirm you’re obtaining an adequate specimen. (We’ve had cases where the specimen was “lost in processing.”) You may also want to consult with the pathologist when choosing a biopsy site (more on this later).

• Do you have all the right tools and toys? Certain instruments are crucial for performing a FTRCB. We all have several instruments at our disposal that can cut posterior segment tissue, but it is important to achieve a biopsy with minimal specimen damage. We have found vertical scissors with a sharp tip (automated or manual) best suited to cutting the retina in a precise manner without losing valuable tissue as with a vitreous cutter, although we have used 25-gauge cutters for this maneuver.

You will also want to make sure you have intraocular forceps, a working diathermy and a lighted pick on hand. We routinely will place a chandelier light to allow for adequate illumination when performing bimanual maneuvers. Finally, we prefer valved cannulas as they allow better control of intraocular pressure, which is particularly important in these cases because achieving hemostasis can be a challenge.

• Choose the ideal biopsy site. Aside from appropriate patient selection, choosing the right biopsy site is conceivably the most important step. The site should involve the pathology of interest, but selecting an area that involves both the abnormal tissue as well as adjacent normal tissue is important so that the pathologist can compare both. Also, selecting an “edge” of abnormal tissue may be important for identifying areas with active disease, especially in suspected choroidal lymphoma. These tumors may consist largely of necrotic tissue, so specimens ideally should include the deeper part of the lesion, near the choriocapillaris where viable lymphoma cells are most likely to be found.11

When choosing a biopsy site, consider potential complications. Often, the pathology in posterior uveitis, primary vitreoretinal lymphoma and choroidal lymphoma involves the posterior pole. Remember that if a major artery or vein crosses the area of interest, it must be cauterized, which will cause non-perfusion distally. You will also want to be in an area that facilitates tamponade. This is especially important as larger biopsies inevitably cause biopsy-site fibrosis and some degree of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. So an inferior site (especially if anterior) is less desirable.

• Beware the unavoidable. Consider specific intraoperative challenges before surgery. Remember that in these cases, the eye is usually injected, the conjunctiva bleeds a lot, posterior synechiae may be present and media opacity issues may arise—all of which you should account for in your planning (Figure 2).

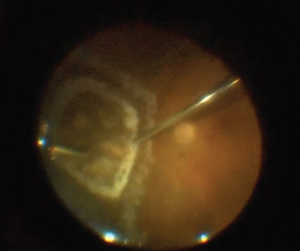

| Figure 3. Intraoperative still image of the biopsy site shows where endolaser was applied to barricade the nasal area up to the far periphery. A more confluent circle of laser was applied to immediately surround the area of retinitis and deep endodiathermy was applied to the inner laser barricade to help initiate the retinectomy |

Once you choose a biopsy site and you are ready to proceed, start by performing a thorough vitrectomy. If possible, peel the hyaloid off the site of interest to facilitate the biopsy and prevent postoperative traction and fibrosis. Complete vitrectomy is also important to allow for adequate tamponade and possibly prevent complications associated with PVR. Keep in mind that patients often may have already undergone diagnostic vitrectomy before the chorioretinal biopsy surgery.

If the patient has significant exudative retinal detachment, consider performing an anterior drainage retinotomy and flattening to posterior retina (which may include the biopsy site) with perfluorocarbon. You cannot take retina, retinal pigment epithelium and choroid in an area of retinal detachment unless it is flattened first.

When you are ready to begin the actual biopsy portion, start by diathermizing large vessels on all sides of the biopsy site and consider diathermizing an outline of the biopsy site to prevent bleeding. Remember, this is not just a retinal biopsy, but also a retino-choroidal biopsy, so be sure to put moderate posterior pressure on your needle-tip cautery during this step so as to also cauterize choroidal vessels.

This brings you to the point where you are ready to excise the tissue, but there are a couple things to consider before you actually start cutting.

Bimanual technique is helpful for an appropriate biopsy, so consider placing a chandelier, if available. Also, as hemostasis is one of the biggest challenges you face during the biopsy, elevate IOP to 50 mmHg or greater just before you start cutting the specimen.

|

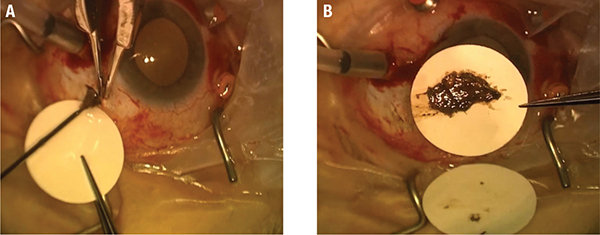

| Figure 4. The sclerotomy has been enlarged, cannula removed and infusion line pinched, and the filter paper held by the assistant is ready to receive the specimen as it is removed from the eye (A). Then the intact retino-choroidal section is flattened and spread on the filter paper (B). |

Removing the Specimen

Just before removing the specimen, remove the cannula (if used) and enlarge the sclerotomy through which you plan to extract the specimen. A small sclerotomy will cause significant tissue damage during specimen removal. However, beware that a large sclerotomy in the presence of elevated IOP can create significant turbulence that can easily sweep your specimen into the vitreous cavity.

That said, as your last step before removing the specimen, pinch your infusion to prevent excessive turbulence. Finally, have filter paper and an assistant ready to “catch” the specimen as you remove it from the eye (Figure 4, page 23). Usually the specimen can be removed en-bloc, but sometimes the retina and RPE/choroid come out in separate layers.

Apply retinopexy around the biopsy site, check for peripheral breaks and place tamponade. We typically use silicone oil for tamponade, although that can depend on the specifics of the case and location and size of the biopsy.

|

| Figure 5. At six months postoperatively, extensive laser barricade is still evident. This patient had some residual hemorrhaging immediately after the biopsy, but it resolved. |

Retino-choroidal biopsy is not a routine procedure and does carry significant risks, the most notable, and perhaps most controversial, of which is the contention that surgical manipulation of malignant lesions promotes metastases. This has not been observed in the limited number of published case series, although most of these series have had relatively short follow-up periods.1,3,12

Patients undergoing FTRCB are at risk of complications accompanying other types of vitreoretinal surgery— cataract, vitreous hemorrhage and retinal detachment. The data on postoperative complications after FTRCB is somewhat limited because this is a rarely performed procedure and the number of case series in the literature is limited. Not to mention that the available data is further limited because many of these eyes go on to be enucleated based on the histopathologic diagnosis.3,5,10,12,13

That said, a review of the available data suggests that the overall complication rate is between 10 and 20 percent, with vitreous hemorrhage and cataract being the most common complications.1,3,5,12,13

Retinal detachment is obviously a concern and was reported in 10 to 15 percent of patients, although follow-up was somewhat limited. Given that these eyes often have significant inflammation, PVR is perhaps the most feared complication, although the exact incidence has not been reported.

In the rare situation that conventional diagnostic and/or treatment measures fail, a vitreoretinal surgeon experienced in this technique may consider FTRCB. Hopefully the considerations discussed here will help you be successful in these challenging situations. RS

REFERENCES

1. Johnston RL, Tufail A, Lightman S, et al. Retinal and choroidal biopsies are helpful in unclear uveitis of suspected infectious or malignant origin. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:522-528.

2. Rutzen AR, Ortega-Larrocea G, Dugel PU, et al. Clinicopathologic study of retinal and choroidal biopsies in intraocular inflammation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119:597-611.

3. Kvanta A, Seregard S, Kopp ED, All-Ericsson C, Landau I, Berglin L. Choroidal biopsies for intraocular tumors of indeterminate origin. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:1002-1006.

4. Cassoux N, Charlotte F, Rao NA, Bodaghi B, Merle-Beral H, Lehoang P. Endoretinal biopsy in establishing the diagnosis of uveitis: a clinicopathologic report of three cases. Ocular Immun Inflam. 2005;13:79-83.

5. Mastropasqua R, Thaung C, Pavesio C, et al. The role of chorioretinal biopsy in the diagnosis of intraocular lymphoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:1127-1132 e1121.

6. Rothova A, Ooijman F, Kerkhoff F, Van Der Lelij A, Lokhorst HM. Uveitis masquerade syndromes. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:386-399.

7. Grange LK, Kouchouk A, Dalal MD, et al. Neoplastic masquerade syndromes in patients with uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:526-531.

8. Davis JL. Intraocular lymphoma: a clinical perspective. Eye (London). 2013;27:153-162.

9. Coupland SE, Bechrakis NE, Anastassiou G, et al. Evaluation of vitrectomy specimens and chorioretinal biopsies in the diagnosis of primary intraocular lymphoma in patients with masquerade syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:860-70.

10. Moshfeghi DM, Dodds EM, Couto CA, et al. Diagnostic approaches to severe, atypical toxoplasmosis mimicking acute retinal necrosis. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:716-725.

11. Coupland SE, Damato B. Understanding intraocular lymphomas. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2008;36:564-578.

12. Cole CJ, Kwan AS, Laidlaw DA, Aylward GW. A new technique of combined retinal and choroidal biopsy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1357-1360.

13. Bechrakis NE, Foerster MH, Bornfeld N. Biopsy in indeterminate intraocular tumors. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:235-242.